John Chiara's Unique Photographs

John Chiara makes large-scale, unique photographs using a camera of his own design. If you were to catch him on the mobile early on a work day, he might say, “Hang on while I park the camera.” The Big Camera, as it has become known, is roughly the size of a U-Haul, which Chiara has driven all over the San Francisco Bay Area, creating mural-size images of landscapes that evoke a preternatural meeting of earth, sky, and human intervention. Each image is identified by its location, yet the information in the pictures transcends description, inviting viewers to connect with their own experience of space and time.

Notions of photographic truth and memory are both inherent and veiled in these expressionistic images. Chiara has written on this subject, “Photography has a long and complicated relationship to memory and the madness of the self-encounter. I find that strong visual memories are produced because of their psychological connection to moments of intense self-reconciliation. As time passes, what was being reconciled becomes no longer attached, but the psychological weight burns the visual into memory. Visual memory seems to always be in flux. Memories are unbound, with divergent edges. You have to move around in them to get to points of clarity.”

Two years ago, he began photographing in New York City and along the

Hudson River Valley, in advance of his 2016 show at Yossi Milo Gallery. Info This fall, a long anticipated monograph is being co-published

by Aperture and Pier 24 Photography.

Following is an extract of an interview with Chiara for DART at the time of his 2011 New York exhibition at Von Lintel Gallery. Info

© John ChiaraThree images from the Starr King: Coral Beacon series

Peggy Roalf: What kind of pictures did you make when you first became seriously interested in

photography?

John Chiara: I think I have always been seriously interested in photography. I was seduced by it at a very young age. I grew up sitting in a darkroom

watching my father develop black-and-white prints under a red light. Watching the image come out of nowhere was magical to me, as a child. Since then I have used photography primarily as a method

consisting of careful observation, pre-visualization and intuition. The pictures I have taken throughout my life have for the most part been of nothing in particular.

PR: When did the idea of personal vs. photographic truth vs. photo-historical memory become part of your ethos?

JC: In 1994 I graduated from

college and moved back to the Bay Area. At this time I got a job at a lab. A sweat shop really. The one good thing about it was that the job was not very stimulating in any way. I was able to spend

eight hours a day [at the lab] thinking over what I was reading, mostly biographies of important writers and photographers. I also spent this time thinking about the photographs I was making, what

photography is, ideas about photographic memory, etc. These things tend to seep into your work. This went on for years.

PR: Has living in the Bay Area influenced your

approach to photography?

JC: In a way, yes. I definitely am influenced by what is right around me and the Bay Area has the right ingredients. I am able to find the

images I want to make here. Also, over the years I have been able to carve out just enough space in San Francisco to develop my process.

PR: What were you working on when

you realized that you needed a specific type of camera, one that you would build yourself, to get the kind of images you had in mind?

JC: Once I started contact printing my

2-1/4 negatives from my twin lens camera, I realized that I could never enlarge an image again. This was in 1994. I was working on a series of images that are strikingly similar to the images in

the Fort at Lime Point series. I was photographing the same sculptures at Laney Junior College and paring them with photographs of barren slopes that resemble the Fort Barry

Shooting Range photograph in the show.

© John Chiara, E33rd Street at Second Avenue, North, 2016; courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery

PR: Your images have an electric quality that results, in part, from your hands-on process of incorporating both shooting and printing into a single activity. How did this approach first strike you as a possibility? How did you cultivate the kind of patience it must take to work at such a slow pace—making one, or at the most, two images per day?

JC: In 1999, after spending much time and energy, isolating objects in my studio and making large macro shots of them, I felt the work was getting too heavy on precision, technique, and effect. At this point, there was a shift in my approach to methods more rooted in psychology—both in the process of making the work and in the effect it would ultimately have on the viewer. So I built a large camera and mounted it on a flat bed trailer. The size and nature of the equipment physically forced the process beyond my ability to control it completely. Like a psychological event, the outcome of each shooting session can never be fully known for sure. I have to use a lot of intuition in making the work, which is based from the experiences of the work done previously. For this show, after watching the negative transparencies I was working on not turn out right on the third attempt, a lab tech said I was crazy to go back and do all the work over again. It caught me off guard. I think of this process as the work. That is where my mind is at.

© John Chiara, Dr. Tom Waddell Place at Polk Street; courtesy Haines Gallery

Editor’s Note: following is an extract of an interview John Chiara did for Aperture’s blog, in 2016, prior to his show at Yossi Milo Gallery.

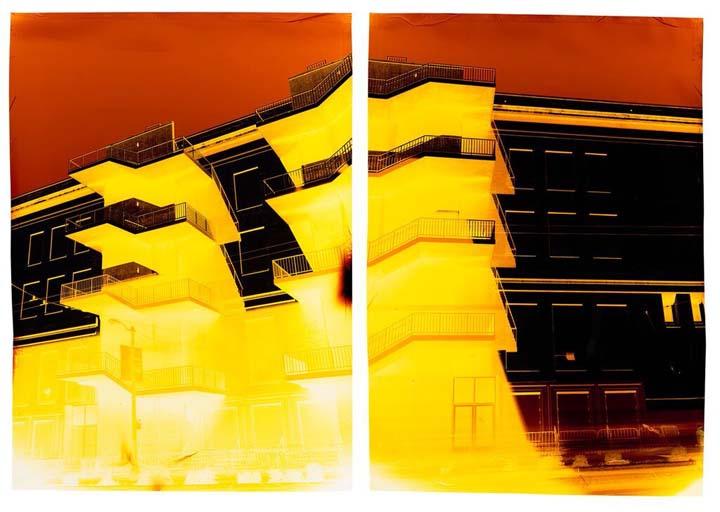

Allie Haeusslein: Why did you decide to invert the color palette for the photographs made around Manhattan?

Chiara: There are too many reasons to mention them all. When I was contemplating the possibility of photographing in New York, I started experimenting shooting directly onto chromogenic paper on the streets of San Francisco. This process not only physically inverts an image and its colors, but also reverses light and shadow. It creates an image that is profoundly more graphic. Subtle changes in light gradations on architecture become more visible as its saturated negative in the photograph. I believe the negative has subliminal qualities and exposes the underlying properties that make up the landscape.

Allie Haeusslein is the Associate Director at Pier 24 Photography in San Francisco. Read the entire interview here.

Information about John Chiara: California here

Land’s End: California at Larkin, new work by John Chiara, opens on November 2 at Haines Gallery, 49 Geary Street, San Francisco. Info See the DART feature on Chiara's first solo show at Von Lintel in 2008, Land's End Info CV19.EX.PHOTO

John Chiara (born in San Francisco, 1971) received a BFA in photography from the University of Utah in 1995 and an MFA in photography from the California College of the Arts in 2004. Most recently, he was artist in residence at Budapest Art Factory (2017) and Crown Point Press, San Francisco (2006, 2016). In 2011 and 2013, the Pilara Foundation in San Francisco commissioned work that was included in group exhibitions at Pier 24 Photography.