Susan Wides's Bookcases

Susan Wides, a photo artist who traded NYC living for a new home upstate, near Catskill, during the Pandemic lockdown, is a long-time DART subscriber and contributor. Recognized for her innovative use of shift-tilt distortion in large-format photography to explore perception and presence, her work was first featured in AP17, in 2001.

Since her immersion in the wildness of her present environment, the images she creates have become increasingly abstract and painterly. Done using digital cameras. It has been observed that her recent series, Voice of Silence subtly alludes to the thought of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. The following interview was conducted by email.

Peggy Roalf: Do you remember the first art book you ever purchased? Why did it catch your attention?

Susan Wides: The first art book I bought for myself was Diane Arbus. I got it the year of her landmark MoMA show in 1972 — it cracked something open in me. Her way of seeing was strangely familiar, deeply human. Before that, my first inspirations came as gifts: a tiny Matisse Jazz (1957) and Fantastic Art: Dada and Surrealism (1936) — my aunts acquired these at MoMA when they were published. These artists were early teachers — Arbus for her unsettling vision, Matisse and Surrealism for freedom and improvisation. They gave me permission to think and make.

PR: How many libraries do you have? How do they differ? Where are they located?

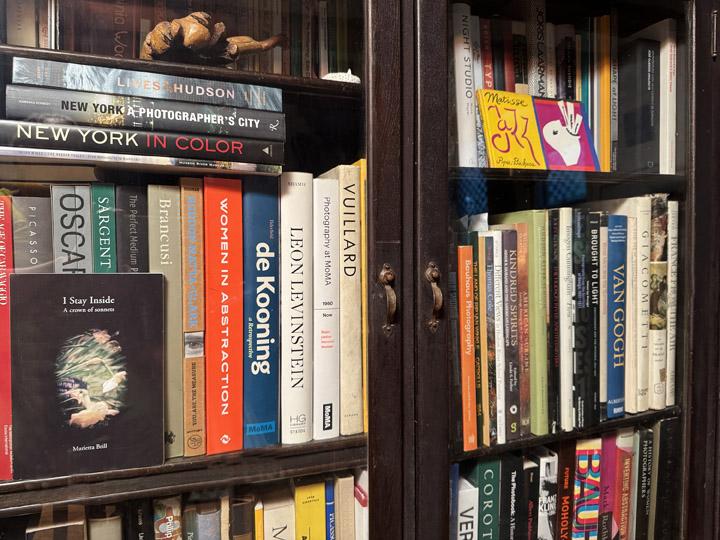

SW: My home library in Catskill [top] is my lifelong companion — shelves of books I’ve carried since high school, through college, every move. They hold the DNA of my life and work: art, philosophy, poetry, literature, spiritual traditions. A second library was the one that was lost. After leaving our 30-year loft in Union Square, my husband and I moved hundreds of books to a storage unit upstate while building shelves at our new place. A week later, Hurricane Irene came — the creek overflowed and flooded the unit. Thousands of books ruined overnight, including journals and sketchbooks. That loss reminded me a library is never just paper — it’s a record of your interior world. I still look for books and realize they were lost in the flood. Some can’t be replaced.

PR: What went into your choice of bookcases — any research? Any seen/envied among friends or colleagues?

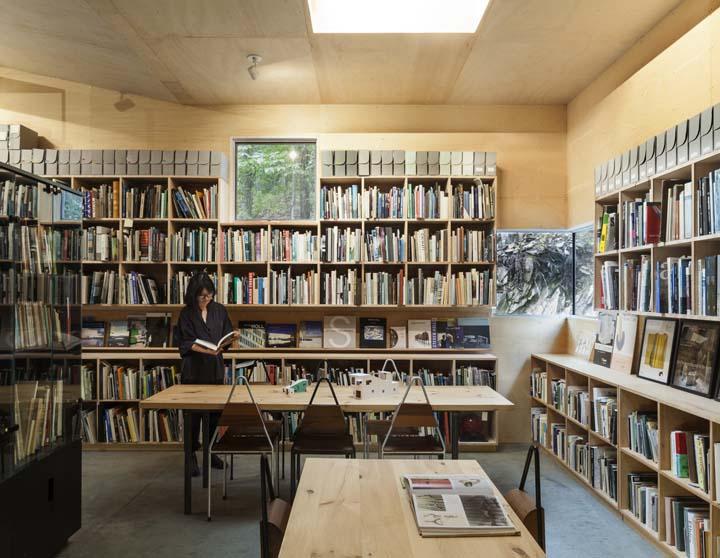

SW: In our Manhattan loft, we built shelves suspended with wire and brackets, wrapping the bedroom — the books encircled us like memory and possibility. Upstate, we added suspended shelves again and glass-front bookcases. At SMHF, the bookcases are part of the building — Steven’s design integrates them with the Archive’s architecture, framing the books as living parts of the space.

PR: Please share some ideas about organizing all the different kinds of books and objects that inhabit your library.

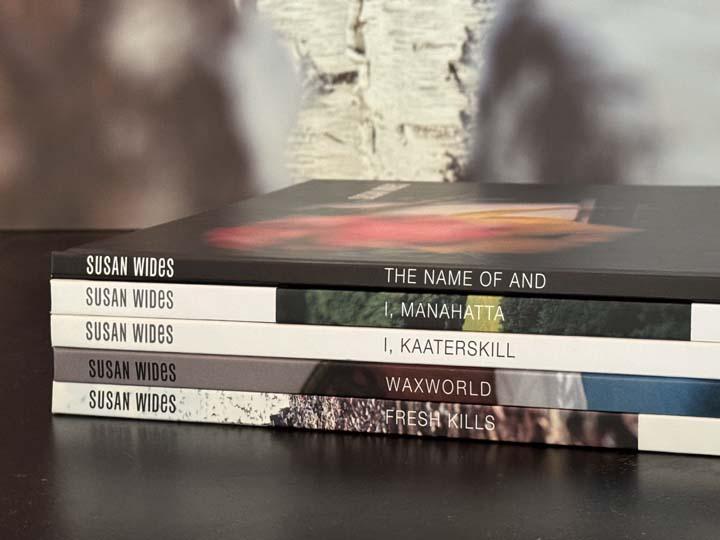

SW: At ‘T’ Space, it’s highly structured — art and architecture mixed alphabetically, then sections for philosophy, urban and landscape design, poetry. They sit side by side to cross-pollinate. At home, it’s looser. Art and photography books drift into theory, then poetry, then biography. I like the mixing — it reflects how my mind works. Some shelves hold sketchbooks, family papers, and objects that tie ideas to memory. Right now, I’m designing a slipcase to house five related books of my photographs — they’ll live together as a single set on the shelf.

Every body of work I make is rooted in books. Waxworld began when I found that uncanny Arbus photo of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor in wax — it sent me back to my Dada and Surrealism book and Susan Stewart’s On Longing. The Name of And began at Brooklyn Botanic Garden in 1990 with words — reading plaques— how language frames nature. The roses honored friends lost to AIDS. Reva Wolf gave me The Culture of Flowers — I paired it with Luce Irigaray’s feminist theory. Their words fed an artist’s book layering text and image. Mobile Views grew from landscapes and my fascination with interwar European photography’s sharp and blurred still-lifes. I wanted areas of focus but disrupted them: I used my 4x5 large- format camera, tilting the lens to shift sharpness in and out — cinematic, like a moving image that never resolves. Baudelaire’s flaneur hovered behind it—perception and embodied presence.

In the Catskills, history is embedded in the land. Books on Thomas Cole through Barbara Novak’s Nature and Culture and Emerson’s essays reframed the landscape as both material and mirror in my I, Kaaterskill photographs, begun in 1997. Voice of Silence grew from the same terrain — walking the creeks near Catskill, letting water guide the lens. Poet Robert Kelly saw the images and wrote ekphrastic poems in response. The title echoes his lines and Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring — listening for what’s gone quiet, ecological and spiritual.

PR: How do you maintain your library? Do you reorganize? What do you do when you run out of shelf space? Do you ever weed out books?

SW: When I run out of space I weed out what I no longer need. After the flood, clinging too tightly isn’t the point — what matters is staying alive to what feeds the work now. Now and then, I rearrange — by theme, project, or instinct. Moving things helps me see connections again.

PR: What are the best and worst things about moving this kind of collection?

SW: The best part is rediscovering — you touch each book again, notes fall out, things you’d forgotten surface. The worst was the flood. That loss shaped how I hold my books now — companions, and fragile.

PR: Is there anything you’d like to add about favorite libraries for research?

SW: The New York Public Library is wonderful — the people, the hush of the stacks, that slip of paper, the old book surfacing from deep below. Since moving Upstate, the Bard Center for Curatorial Studies Library is my go-to. My studio and library are one long conversation of making and thinking.

PR: Do you consider being a bibliophile a form of madness?

SW: If so, I’m fine with that. Books are collaborators. My work starts with intuition — an image, a question, a tension — but books give that impulse shape and challenge. Poetry, ecology, the spiritual, neuroscience—and more— all touchstones. My shelves hold ideas I carry into the field, the studio, the lens. In this moment, books comfort and guide — steady companions through chaos and reactionary times. They remind me, as someone shaped by the flowering of the ’60s and ’70s, that thought endures — ars longa, vita brevis.

Susan Wides is an internationally recognized photographic, video, and installation artist based in the Hudson Valley, with four decades rooted in NYC. Her work explores perception, abstraction, and ecological presence through intuition and research. Exhibited in 100+ shows worldwide, her work is in over 20 museum collections around the world. A Hudson River Museum survey highlighted her multidimensional landscapes. Her work is widely published, and she lectures frequently. Susan is the Curator and Director of the Steven Myron Holl Foundation | ‘T’ Space, an interdisciplinary arts and architecture venue where she has curated 42 exhibitions that unite art, architecture, poetry, and music.

Website: @susanwides: https://susanwides.com/

Instagram: @susanwides

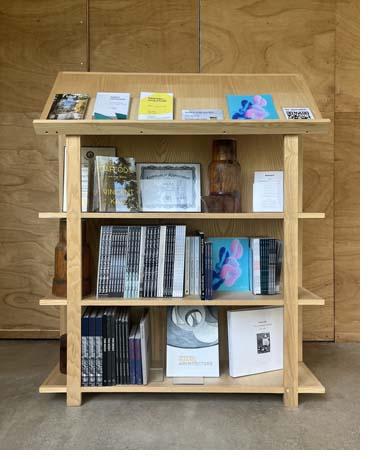

‘T’ Space/SMHF has special programming for Upstate Art Weekend this Saturday and Sunday: a Robert Grosvenor exhibition in the Archive Gallery; free campus tours will include the Architecture Archive’s permanent exhibition of over 1,200 models, the Research Library, plus the acclaimed Ex of In House.

Susan has an installation of her photographs at the ‘T’ Space Gallery, in dialogue with Peter Halley’s wall painting and the gallery’s architecture by Steven Holl. It’s available for visitors on Upstate Art Weekend, and by appointment at other times by contacting sw@susanwides.com

Visitors are invited to see the art and step inside the shelves that hold the questions behind our work at the Gallery and the Archive. The books are there waiting — just like the art and the landscape.

SMHF Main Campus is located at 60 Round Lake Road, Rhinebeck NY 12572 .‘T’ Space Gallery is at 125 1⁄2 Round Lake Road, Rhinebeck NY 12572.

T Space is open Upstate Art Weekend, but other than that by appointment only via sw@susanwides.com :or by paid tours—please sign up on website. Hours: July 19, 20—Saturday and Sunday from 11 – 5 pm

Free campus tours on the hour, with the last one at 4 pm

Reservations for tours are recommended on the website, but not required.

‘T’ Space Website: https://tspacerhinebeck.org/

‘T’ Space Instagram: @tspaceandsmhf

All photos by Susan Wides except as noted