Photographer Profile - Petra Barth: "I hope to create an emotional connection between the viewer and the subject"

|

|

|

Barth, who was born in Germany and studied fashion design in Milan, worked in the fashion industry before moving to the United States 13 years ago and enrolling in photography courses at the Corcoran College of Art and Design in Washington, D.C. (Now the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design.)

“I was pretty fed up with the fashion business, and photography was sort of a lifelong dream of mine,” she says.

At first she didn’t know what kind of photography she wanted to do, but an interest in social issues in developing countries — sparked during travel to India at age 23 — led her to documentary work. In Germany she had avidly read Latin American literature, and soon after enrolling at the Corcoran she decided to take her cameras on a road trip to Central America and Mexico. The journey cemented her dedication to documentary photography.

“I didn’t have a plan and didn’t want a plan,” she says. “I wanted to experience what I saw, not to go with a preconceived subject in mind. I got involved pretty deeply in photographing small rural communities, in El Salvador and Guatemala, and when I came back I had tons of photographs.”

She showed them to one of her teachers as the Corcoran, Andy Grundberg, formerly the photography critic of the New York Times, who advised her to look at the collection of photography from different places within a bigger framework.

“She’d been traveling all over, and she said, ‘Here is my work from Nicaragua, here are my pictures from Mexicali,’” Grundberg recalls. “I said, ‘Isn’t this work really about all the Americas, as opposed to just these different places you’ve been?’”

He also told her to study the work of Robert Frank. “It was an aha moment for her,” Grundberg says. “It shows you where she was coming from — she hadn’t heard of Frank. But he became a big inspiration for her.”

His suggestions have had a powerful effect of Barth’s life and work.

Heeding Grundberg’s advice, she continued her travels, but with a new focus, having conceived of a longterm project she called “Las Americas,” a view of daily life in locations stretching from Chile and Central America to the United States.

“I went to places that people don’t normally go, villages, towns and smaller cities — the kinds of places that are never reported on, except when there’s a natural disaster and the media comes,” she says. The black-and-white work, which until 2014 was shot on film, includes portraiture, landscapes, and reportage.

About four years ago, Barth’s journeys came to a standstill at the U.S.-Mexico border. There she embarked on a series that has marked another stage in her evolution as a photographer.

Barth arrived in the area as the United States was building up enforcement measures, including a fence, to keep undocumented migrants from entering the country. In the divided city of Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora, she began documenting life on both sides of the border.

“I followed deported migrants as well as people who tried to cross the border in an attempt to find work or reunite with families living in the U.S.,” she writes about the work. “I wanted to know more about these people — often referred to as migrants or illegals — and learn why they risk their lives to cross the unforgiving desert.”

In Nogales, she contacted two nonprofits, — on the U.S. side, a group called the Border Community Alliance, which works to bridge north and south with cross-border tours and social and education programs, and on the Mexican side a community organization called FESAC, or Fundación del Empresario Sonorense (Foundation of Sonoran Entrepreneurship). Through FESAC she was led to the San Juan Bosco shelter, a way station of sorts for people who have been deported from the U.S.

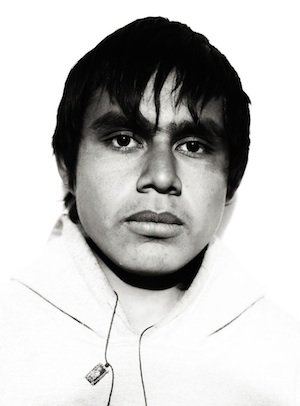

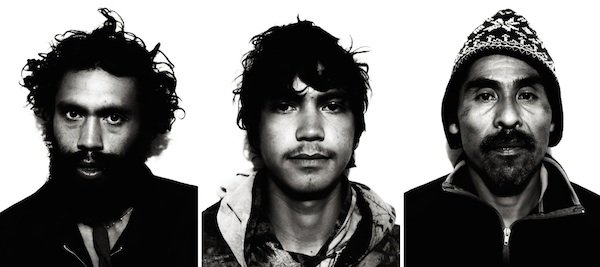

There Barth began a series of portraits of the people passing through the shelter. She titled it “Los Mochileros,” or “The Backpackers.”

Barth notes that in recent years increased border enforcement by the U.S. has significantly slowed the number of migrants crossing the border illegally. (See this 2016 report from Pew Research Center.) “As a result, the Department of Homeland Security estimated in 2015 that the probability of getting caught by the border patrol was 54 percent, up from about 36 percent in 2005,” she writes in a statement about her “Backpackers” project. “Despite the fact that fewer migrants try to cross into the US, the misery of those who do is shocking, and their suffering is profound.”

Her portraits, shot with her subjects posed against a bare white wall and uniformly framed, form a typology of the misery.

Barth has made five trips to the shelter over the years, always photographing the deportees in the same room — a space lit by a single fluorescent light fixture that doubles as a

chapel.

“It was really dark, the worst you can imagine,” she says.

The entire series was shot with a Leica Monochrom camera; Barth later compensated for the poor lighting in Photoshop.

Almost everyone she approached at the shelter wanted to be photographed, she says. “I asked permission, and then I would be alone with them for a while, waiting for the right moment to photograph them, when they were at ease with me,” Barth says. Her goal, she says, was to put the focus on the faces of these people she met in the shelter.

Her work has been entirely self-financed. “I have not received any grants yet, even though I applied to many of them and did not give up the hope,” Barth says. “The financing part was very hard and often made me question my work and wonder if it would be better to drop everything. I had to put in much of my own savings, and I sold some prints along the way.”

“When you meet someone as a student, you’re always skeptical about how its all going to turn out — some people disappoint you and some people amaze you. Petra's one of the people who amazed me,” says Grundberg. “She dedicated herself to learning photography, at the Corcoran and in workshops with other photographers, and she has pushed herself and gone about her work with very little in the way of public acknowledgement.”

The acknowledgement is now coming. Last summer, Barth’s “Backpacker” portrait series was shown at the Houston Center of Photography, and this year it will be exhibited at the Venice Biennale, from May 13 through November 26.

The timing is important, as the United States moves toward building the border wall that Donald Trump promised during his presidential campaign.

In Nogales, the busiest international crossing in Arizona for workers and a hub for international trade, Barth was introduced to the complexities of trans-border culture and economics. She says that many of the people she spoke to, on both sides of border, are wary of a wall. That impression is born out by a Cronkite News-Univision News-Dallas Morning News poll published last July, which found that the majority of residents of U.S. and Mexico border cities oppose a wall.

In the dimly lit room at San Juan Bosco shelter, Barth put the focus on the faces behind the numbers, and in doing so found her voice as a documentary photographer.