Photographer Profile - Sarah C. Butler: "I would use the only tool I had, my camera"

|

|

|

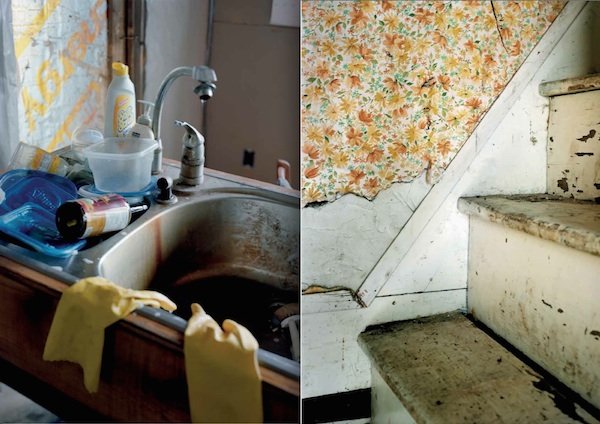

The book is about Butler and her mother, though strictly speaking it’s about a house. In its forward, critic Vicki Goldberg calls Frozen In Time “a psychological narrative and a highly unusual one at that.” The narrative reveals itself amid a mess of details Butler photographed over the course of several years — dirty dishes, peeling wallpaper, piles of magazines, faded mementos — and it defies easy summary, as untidy stories do.

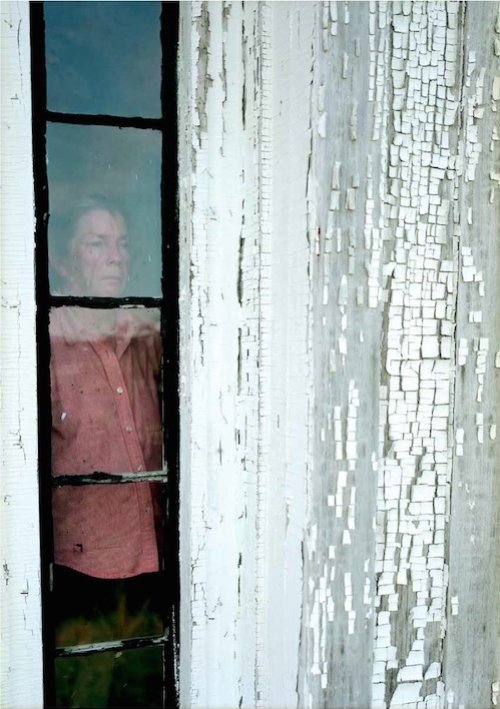

In one sense, it began in 2009, on the day that Butler received a phone call and learned that her mother’s health was deteriorating. She traveled from her home in Boston to the farm in Maine where her mother had been living for the past 16 years and was dismayed by what she found. “It was 45 degrees inside the house and she was in layers of clothes. She hadn’t showered in weeks, and she was just crying,” Butler says. “If she’d been walking down the street, I wouldn’t have known her.”

Butler, who hadn’t visited her mother’s home in eight years, was not warmly welcomed. That part of the story goes back well beyond 2009.

“As a kid,” Butler says, “I never got along with my mother — I sort of hated her and blamed her for my parents’ divorce and for taking us away from the life we had had.”

Butler grew up in the town of Mount Desert, on Mount Desert Island in Maine. Her parents divorced when she was in the second grade; she and her sister Rachel lived with their mother, while her father built a home about a mile away. “My sister and I were taken care of by babysitters, sent to summer camp and boarding school, so I felt abandoned, though at the time I didn’t recognize it as such,” she says.

Her mother, she writes in her book, was a woman “who seemed to glide through life with elegance and grace.” The daughter of a doctor, she grew up in a stately home and formal way of life. “In raising us, she rejected the formalities of her own upbringing. Yet she herself never lost the airs and attitudes of that background,” Butler writes.

Butler was grown when mother fulfilled her longtime dream of living on a farm with animals. The house she bought with money she’d inherited was broken down, as was a barn with a small apartment in it. And they remained that way.

Emptiness and Disarray

“When she moved to the farm, she didn’t know anyone and was very isolated. She didn’t have a job or responsibilities or commitments, and I think that affected her,” Butler says. “She was also a drinker, and all of that led to depression. Basically, it was a perversion of someone deciding that she was going to have it her way.”

Butler says that when she arrived at the farm in 2009 her first reaction was to run. Instead, she decided to stay and photograph her mother’s neglected home.

“Unconsciously, I began this work viewing my mother as if I were still eight years old, and this house was proof that she had failed me again,” Butler writes in the book. “The unfinished interiors, the broken-down exterior; emptiness was all I could see.”

She made a dozen trips to the farm that first year to photograph the house, but only one of the images she took resonated with her — a shot she made when she found dresses that she and her sister had worn as children. “It was something I could at least relate to,” Butler says. Because of that picture, she made a commitment to return and photograph more often.

“I came back three or four times a week and would photograph for two hours at a time,” she says. “Sometimes my mom was okay with it, sometimes she kicked me out, and sometimes she was passed out. It was, ‘Sarah, why do you come here photographing every day? Haven’t you been here enough?’ Because of the house and the way it was, all I could do was shoot. It was like being on survival mode.”

It was only after two years of photographing the house that Butler began to look closely at her contact sheets. “That is when I started falling in love with the light in the house and how it fell throughout the space,” she says. Month after month, year after year, she photographed the house, and sometimes her mother. Butler shot mostly with a large-format 5x7 camera, which meant she worked slowly and deliberately. “I was able to be still in the emptiness and disarray,” she writes.

A Catalyst for Change

Photography, the act being still and seeing, has been a catalyst for change in Butler’s life. In her book, she describes her initial decision to photograph her mother’s house as an act of desperation, if not self-defense.

“I realized this time I had to stay,” she writes. “I would use the only tool I had, my camera, the one thing I had ever trusted to guide me where I needed to go.”

Butler says she was a rebellious kid. “I got kicked out of a lot of schools. I drank a lot, so my mom and I had that in common, and the behavior patterns that come with that,” she says. The last school she was kicked out of was Rockport College — now the Maine Media College — where she’d been taking some photography courses. She had shown up to a class drunk. Several months later she was in a car accident that nearly took her life.

“There was no permanent damage, but the accident changed something in my head. I knew I was never going to drink again,” she says. She reapplied to Rockport College, and this time she fell in love with photography.

“It was a substitute for everything I’d been doing before,” she says. “My teachers said I produced more work than they’d ever seen a student produce.” Later she transferred to the Savannah College of Art and Design in Georgia, where she created a project that became her first book, Portrait of a Maine Island. “I thought of it as a picture album about the place where I grew up. There was no aim behind it. I just enjoyed doing it,” she says.

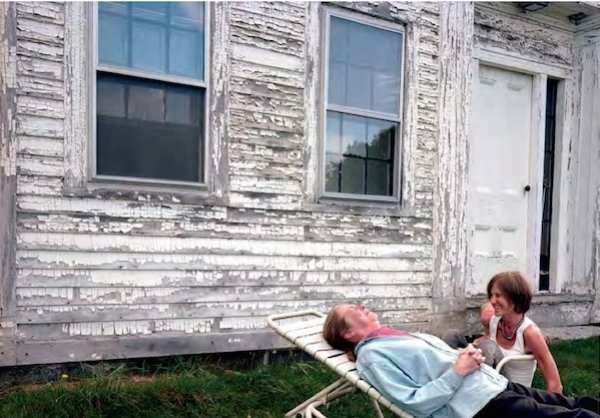

Butler went on to work as a photographer’s assistant in Boston. And then, in 2009, came the call about her mother. Photography worked a change on Butler when she began documenting and then falling in love with the farmhouse. Her mother responded in kind, she says.

“To her, my acceptance of the house was like an acceptance of her,” Butler says. “That sort of opened up a space for a friendship, so a friendship began.”

When she started to organize her work from the house, Butler wrote a short artist’s statement about it. “I wanted mom to look at it, and she said she would do it later. I said, ‘Mom read the statement now.’ It basically was the truth about her life, without being judgmental — the alcoholism, the unfinished business, the feeling of never finding what you’re looking for. She started crying. I thought she was going to kick me out and say never come back. And then she asked me for a copy, which was the most powerful thing.”