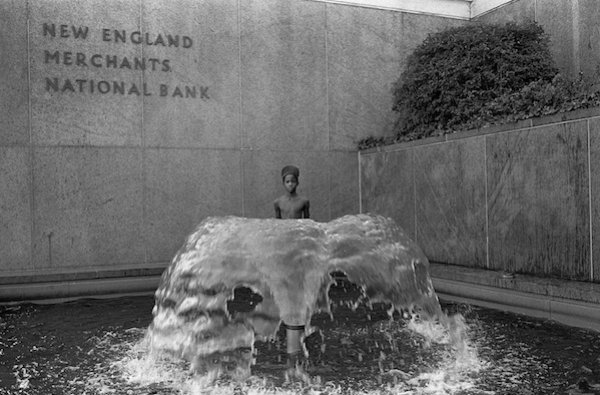

Photographer Profile - Richard Sandler: "I was a street kid - that world was my world"

|

|

|

“I was very happy with the way the work was received, especially since back in the ’80s, when the pictures were fresh, nobody wanted any part of them,” Sandler says.

Sandler’s newfound renown is a case study in the vagaries of taste. In 1967, the landmark Museum of Modern Art exhibition “New Documents” identified what curator John Szarkowski called “a shift in emphasis” and “a new direction” in photography — documentary photography that had the feel of snapshots. The exhibition featured the work of three relatively unknown photographers — Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, and Lee Friedlander. Like many other young photographers during the following decade, Sandler was deeply influenced by the photographs of all three. But by the time he began shooting his own pictures of New York in the early 1980s, the artistic landscape had shifted again.

“It was very difficult to be in the generation of street photographers immediately after Winogrand, Friedlander and Arbus,” says Sandler. “It was difficult to be taken seriously, particularly with the way MoMA canonized them and then closed the door to street photography and moved on to the next thing.”

Shut out of the art world, Sandler carried on, supporting his street photography habit with freelance editorial work for the New York Times and other publications, as well as commercial work. “In a way it was good, because I didn’t really didn’t have any hope of making a mark in the art world,” he says. “I just said, ‘Oh, what the hell, I’ll bide my time and wait for things to change. But things didn’t change, not for many years.”

Then came the age of digital cameras and smartphones, and with them a resurgence of interest in street photography. “Everybody wanted to do it, because street photography is a gas,” Sandler says. Along with that came a fascination with the gritty and dangerous New York of the ’80.

“I’m not into digital myself — particularly the look of digital — but it’s kind of a moot point these days,” Sandler says. “You could make the argument for digital being the way things look now.”

When Form Becomes Content

Sandler shot his pictures of New York with a Leica and Kodak Tri-X black-and-white film, mostly. “I would shoot with any film I could get my hands on, really — Ilford HP5, or occasionally I could get Agfa 400 or 200. I used whatever was cheapest,” he says.

The earliest pictures in the book are from 1977, when Sandler was living in Boston. He grew up in New York City and spent many days skipping school. “I was a street kid — that world was my world,” he says. “I was going to Times Square by myself by age 10 or 11 in 1956. There were so many characters there, and I was fooling around with them — you know, giving shit and taking shit.”

Sandler told Time that he moved to Boston to become a macrobiotic chef. There, he boarded in the home of David McClelland, the psychologist and Harrvard professor known for his work on motivation Need Theory, and his wife Mary. “The house was kind of communal and full of spiritual seekers and intellectuals,” Sandler says. Mary McClelland gave him her Leica 3F in 1977 and taught him how to develop film in a basement darkroom.

“I picked up photography by osmosis,” Sandler says. He also audited a class at Harvard taught by photographer and critic Ben Lifson, who introduced him to work of Kertész, Frank, and Friedlander. “It just blew me away,” Sandler says. “I thought, ‘Yeah, this is what I want to do.’ There was never any doubt.”

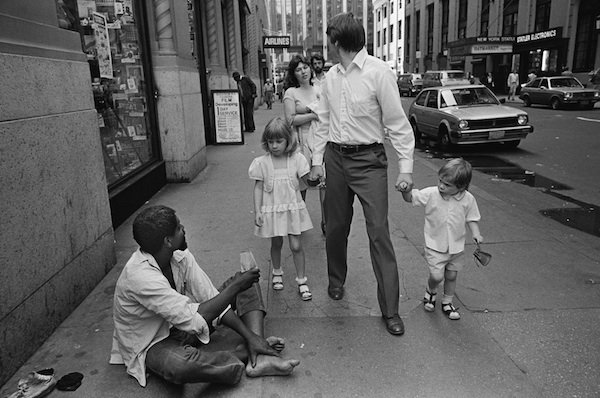

So he hit the streets. “I wanted to get to the nitty-gritty of everyday life, and having grown up in a liberal-thinking Jewish household with parents who were activists, it just made the most sense that going out on the street was the best way for me to express myself and my political leanings,” he says. On the streets, Sandler focused on the lonely and the left-out. “Photography was a way for me to deal with the income inequities of the culture we’re living in and to ask questions about that culture,” he says.

He found, however, that photography is necessarily more than a political tool; it’s also a process that informs how you experience the world.

“Photography has so many wonderful dimensions, and one is just being able to see something with a frame around it. I found that by doing that, the frame became content,” he says. “Winogrand talked about the dialog between form and content — he said the best pictures were the ones in which the form was threatening to overwhelm the content and the content was threatening to overwhelm the form. It became clear to me that the formal aspect of pictures also has content. Whatever jarring or harmonious arrangement exists within the frame is a form of content. It’s not as obvious as the subject matter of a picture, but when form becomes content, you really feel it.”

The Burden of Seeing

In Boston, Sandler began shooting for alternative newspapers — the Boston Phoenix and the Real Paper — as well as the New York Times. “In 1980, the Times told me if I moved back to New York they could give me plenty of work, so I did,” he says.

The city he came back to, filled with crack and crime, was more dangerous than the one he’d grown up in. The pictures he shot captured the toil of life in the city, the worn faces and the wary faces, the rich and poor, the beaten down and the resilient. In the book’s afterword, author Jonathan Ames writes that Sandler’s images display the city’s “play of greed, decay, venality, beauty, longing, hidden meanings, coincidences, love, terror, mundanity, suffering, boredom, loneliness.”

Ames also imagines that the work must have been a burden for Sandler. “I was looking at the things most people were turning away from,” Sandler says. “Some of those things were very troubling.”

By 1992, it was clear the city was changing. That year, Sandler won his second New York Foundation for the Arts grant, and he used the money to start shooting video in Times Square. “I was still shooting stills, but the output took a back seat to the video from ’92 to 2001,” he says. The result of his video work are the documentaries Gods of Times Square, a chronicle of the era focusing on the use of Times Square as place for proselytizing, as well as Brave New York and Radioactive City.

“When 9/11 happened, I put down the still camera completely, because it became obvious to me that the sound on the street — the arguing and the baiting and fighting and mourning — was more important than the romance of the perfect image,” Sandler says. “There was no romance anymore.”