Photographer Profile - Matt Eich: "I do feel a much greater sense of purpose now"

|

|

|

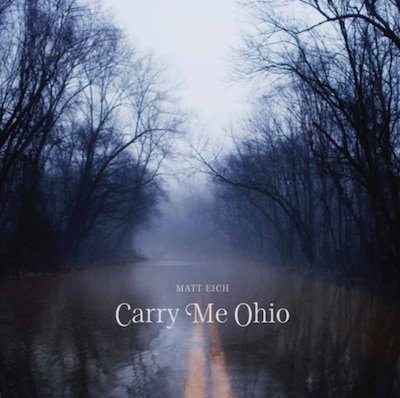

There is gloominess in the work. The pictures capture a region reeling from the coal industry’s decline — an Appalachian landscape of strip mines and trailer homes that stands apart from the shinier corners of the nation. In one, a toddler and a dog look out from behind a cracked window patched with duct tape. A photo from 2012 shows young men smoking weed on Super Bowl Sunday in a room decorated with a Confederate flag. In another image, a young girl stands by a tire skid mark on an empty street, left there when her father drove away. In another photograph, a country road covered in snowmelt disappears into murkiness ahead.

But the series, which has now been collected in the book Carry Me Ohio, can also resonate with a kind of beauty — an appreciation for a place that Eich explored over the course of a decade in which he came of age as both an artist and a man.

“I was fascinated by the haunting hills, the winding roads, and found myself photographing everything: the smokey bars, the strip mines and in the homes of these forgotten communities,” he writes in the book.

Eich began the project in February 2006, when he was a 19-year-old sophomore studying photography at Ohio University in Athens. “It’s this small town in these beautiful rolling hills,” he says. “I’d been around the area outside of Athens a little bit, enough to pique my interest. So I just started wandering around.”

What began as a school photo assignment turned into sociological study of rural poverty and then became something far more personal and nuanced. The same year Eich started the work, he met a girl, and the following year they found out they were going to be parents. His pictures began to explore family life and the bonds that tied the people of the region together.

Later, Eich launched a career as a documentary photographer, and he and his family left Ohio. They live now in Charlottesville, Virginia. But he returned when he could, sometimes for a magazine assignment, sometimes just to visit the people he’d come to know. In the meantime he developed a larger, related project: Eich describes Carry Me Ohio as the first chapter in what will be a four-volume long-form photo essay exploring places in American where, as in southeastern Ohio, the legacies of the past form the backdrop of an insecure present and fearful future.

On November 9, his ambitious project was given a new context, as that insecurity and fear helped make Donald Trump the president-elect of the United States. “Depressed people act in anger, and anger leads to situations like this,” Eich says.

Now his decade-long project has a timely new framework: Eich is no longer just looking at a forgotten America. He’s chronicling Trump’s America.

Making Coal Great Again

“It’s bizarre that it came about this way. I'm still trying to wrap my head around the whole thing. But I can say that I do feel a much greater sense of purpose now in the work,” Eich says.

His project on America is called “The Invisible Yoke.” The volume on Ohio will be followed by one about Mississippi, due out in 2018. “It looks at the legacy of racism and how that affects kids growing up there today,” says Eich. “A few years ago we thought we had gotten past all that and were living in a post-racial world, but now we know we’re not.”

Following that will be a chapter about the area of Virginia where Eich grew up. “It’s the home of the world’s largest naval base. I’m looking at the legacy of the military-industrial complex,” he says. The final volume, due out before the 2020 presidential election, will feature other places and events that Eich has photographed while traveling across America, from the annual rattlesnake roundup in Sweetwater, Texas, to last summer’s Republican National Convention in Cleveland.

The Ohio chapter reflects on the legacy of coal.

“From the 1820s to the 1960s, mining corporations stripped Appalachia of its resources,” Eich writes in Carry Me Ohio. “After taking all that they could, the companies left, leaving former boomtowns with little but their cultural identity. The worship song is some twangy country tune or ‘Oxycontin’ by Lil Wyte. You pray for the past boom to return, with little thought of the busted present or the unknowable future. What future can be expected from a life here?”

One of the memorable images in the new book shows a young man with a tattoo on his neck — a dotted line and the words “Cut here.”

“A lot of people there voted for Trump because he put on a hard hat and said he would make coal great again,” Eich says. “But that won’t happen, because it’s just too expensive to get the coal out of there.”

What America Looks Like

Ohio, writes Eich, was the place that taught him to see.

He became interested in photography as a kid, when his grandfather gave him a point-and-shoot camera during a trip they took together. He worked in a camera store before heading off to college. He says he was in over his head when he started his student work because he didn’t know how to approach people.

“I had to learn to articulate to the people I was photographing what it was that I was doing,” he says.

His break came in a little town called Chauncey, a few miles away from Athens, where he met a man named Jessie Sellers. “He was at a car wash cleaning dirt bikes with his two sons, and I struck up a conversation with him,” Eich says. “He invited me to jump in the back of his truck with the boys, and we drove to his house.” Eich met Jessie’s wife Tracy and his two identical twin daughters, who were born deaf.

Jessie — a welder who spends months away from his family to find work, as well as a self-proclaimed “wild child” — became a friend and introduced Eich to other people in the area.

Crucial to Eich's work was the funding he received from the Economic Hardship Reporting Project, which was followed by a Getty Images Grant for Editorial Photography. “That’s the way it goes — a little funding helps you do some new work, and the new work helps you get another grant, which lets you continue to make more work,” he says.

Along the way, Eich says, he developed a "deep interest" in America.

“I eventually realized through the process that this pile of pictures I was shooting added up to something, but it was hard to say what,” he says.

November 9 put the work in sharper focus. “For a long time I felt like I was shouting into the void with what I was seeing and feeling and hearing in my travels and what I’ve been trying to articulate through my photographs,” he says. “After the election, people are grappling with the reality of what I saw — this is America; this is what it looks like; this is what it feels like; this is what it sounds like.”