Photographer Profile - David Godlis: "I thought, this place is so crazy and so cool, I should be taking pictures"

|

|

|

“I was hanging out around the door and I thought, oh my god, that’s Robert Frank,” he says. “For me, that was the biggest thing that could happen, because I had studied photography and he was one of my idols.”

His friends at the nightclub in Manhattan’s East Village didn’t share his astonishment.

“They were into music, not photography,” Godlis says. “I told them, hey that’s Robert Frank! But they were like, who’s Robert Frank?”

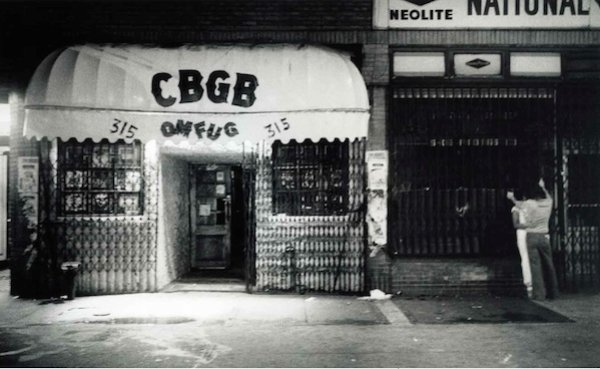

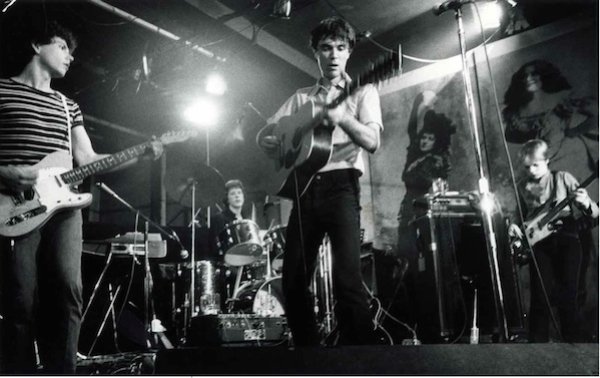

It was the late 1970s, prime time for punk and for a new generation of photographers about to change the medium, Godlis among them. He started coming to CBGB shortly after moving to New York from Boston in 1976, looking for work and a place to hang out and listen to music. What he found was a new home that was open all night.

“I’d seen ads for the place,” he says. “The first time I went there I heard Television. They were new to me, but right away I thought, that sounds like the Velvet Underground. I was a big fan of the Velvet Underground, but there weren’t that many people in 1976 who were fans of the Velvet Underground or the early Rolling Stones records, or who had seen MC5. But the people at CBGB got all that stuff. And I thought, oh, these are my people.”

They didn’t get Robert Frank, though — until Godlis explained that Frank had shot the photo on the cover of the Stones’ "Exile From Main Street" album.

“I thought it was magical that he came into the club. Later I found out that he lived three doors away,” Godlis says. “I was so in awe of him that I could barely have an interaction with him. But I do remember him saying in his Swiss accent, ‘It looks like they way people dress here is very important.’ And you couldn’t argue with him on that point.”

Godlis says that from the moment he walked into CBGB, which was soon after he arrived in New York, he started thinking about doing a photo book. His inspiration was Brassai’s black-and-white photographs of Paris’s nightlife in the 1930s. “I thought, this place is so crazy and so cool, I should be taking pictures here, even though I’m a street photographer who shoots with natural light during the day. I wondered if I could be a street photographer shooting by natural light at night.”

More than 35 years later, his book about CBGB, History Is Made at Night: Photographs 1976-1979, is finally here. Godlis showed the work to publishers over the years, but no one was interested in the grainy images, shot with long exposures instead of flash. “Punk photography was all flash, and this wasn’t,” he says. “And it wasn’t really a music book either, so they didn’t know what to do with it.”

Instead, after decades of rejection, Godlis ran a Kickstarter campaign.

“It was only right to do a DIY book, because punk was a DIY scene,” he says.

Punk Legend

One day something is old news and the next it’s legend. Sometimes success means waiting long enough to be on the right side of history.

There has been a burst of interest lately in the New York of the ’70s and early ’80s — a gritty city that has come to be seen as a mythic crucible for a generation of musicians and artists. Godlis's new book joins recent collections from other photographers of the punk era, as well as a number of exhibitions, including one about the Ramones this spring at the Queens Museum.

Godlis came to CBGB steeped in the history of photography. He had been taking pictures since he got his first camera — a Pentax Spotmatic — while growing up on Long Island. Later he went to Boston University thinking he was going to be a writer, but he came to realize that photography was his future.

“That led me to the library to look at photo books by Cartier-Bresson and other people who interested me — Frank, Arbus, Winogrand,” he says. Most big colleges weren’t offering photo programs at the time, and he ended up taking a class at a small school in East Cambridge called Imageworks, where his teacher was a young RISD professor, Henry Horenstein, and his classmates included two future photographers of note, Nan Goldin and Stanley Greene.

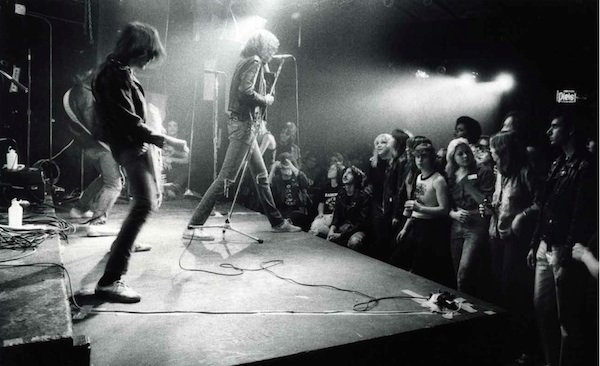

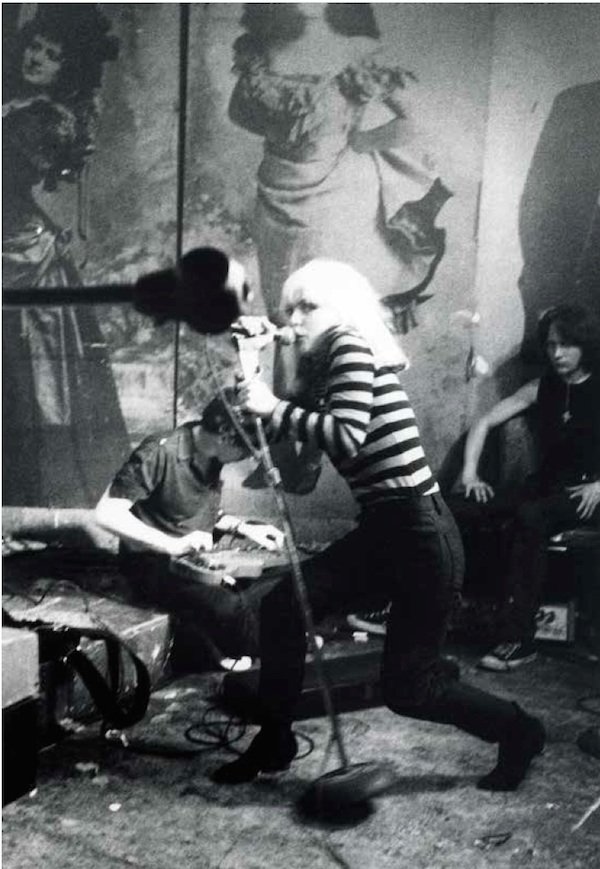

By the time he got to New York, he had a

clear idea of the kind of photography he wanted to do. Though Godlis photographed punk icons like the Ramones, Blondie and the Talking Heads, he was just as interested in the scene on the sidewalk

outside CBGB, the bartenders inside, the bouncers, the girl at the front desk and the club’s flannel-shirted owner, Hilly Kristal.

“Even back then a lot of people didn’t get what I was doing,” he says. “When you shoot with flash in a club, it changes the experience and the way people behave. Other photographers would be shooting these low-angle flash pictures to make the the spiky hair look bigger, and I was there with my Leica. People would say, hey your flash didn’t go off!”

Punk magazine eventually published some of his pictures, as did NME magazine in England. “Rolling Stone couldn’t have cared less,” he says. But Creem magazine in Detroit couldn’t get enough. “I’d send them 25 pictures and they would run them all,” Godlis says. “They’d lay them out like, this is what happened at CBGB on this night. I got five dollars a picture.”

Godlis shot at CBGB for three years, more or less every night. Then the ’70s ended and punk was dead.

Its resurrection began as early as 1981, with the landmark art exhibition “New York/New Wave” at P.S. 1. “I had a wall there, and that started people thinking about my pictures as art,” Godlis says.

Punk FOMO

It wasn’t until Nirvana came along in the ’90s that interest in the punk era really exploded. “Everybody knew that Nirvana hit because of what had happened at CBGB, and I started getting calls,” says Godlis. Then in 1996 came the book Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk by music journalist Legs McNeil. Punk wasn’t old news anymore.

Back when he was going to CBGB, Godlis had a day job as a photo assistant. “I’d get off work around five o’clock, go to my apartment and sleep for a few hours, then get a slice of pizza and go to the club around ten,” he says. “Then I’d be there till three in the morning and close the club and go with some of the band members for a late meal at a diner.”

He was driven by the

fear of missing out. “Those were all my friends. and every night you’d wonder what’s going to happen,” he says.

In the new book’s introduction, filmmaker Jim Jarmusch notes that night people are different from those who prefer the clarity of day. “At night the edges lose definition,” he writes. “In the city every corner or recess, doorway or alley becomes mysterious, alive with a constantly shifting variety of possibilities. One must be ready for them. Living at night requires imagination. In NYC in 1976 it was necessary just for survival.”

Godlis survived to tell the tale.