Photographer Profile - Arlene Gottfried: "It takes a lifetime to be a new discovery, I guess"

|

|

|

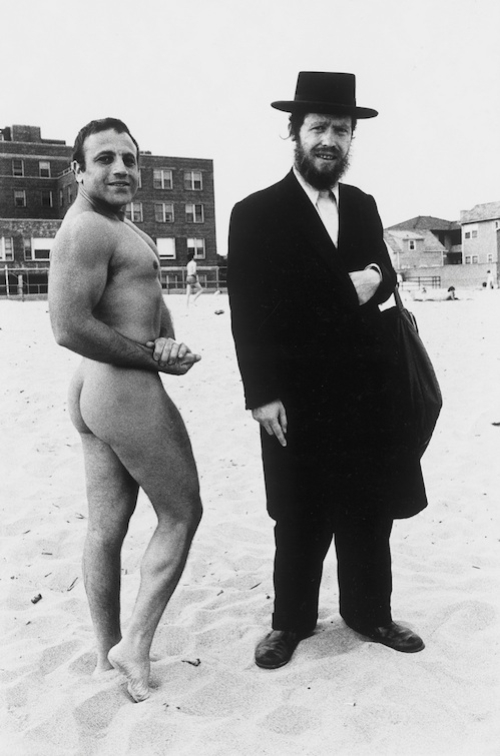

She’s photographed lovers caressing on park benches, the homeless sleeping on subway seats, and choirs belting out gospel songs. She’s captured warm moments of daily life and those odd urban juxtapositions — a muscle-bound Puerto Rican man in a tiny swimming suit standing next to an elderly woman in Brighton Beach; a Hassidic man among the crowd at a nude beach in Far Rockaway — that make the city a smorgasbord for street photographers. As a photojournalist she has worked for Life, Time, Newsweek, Fortune and other magazines and been admired by generations of photo editors. Yet in all those years of taking pictures and all the miles of New York sidewalks she has trod upon, she has never had the kind of attention she is getting now.

All of a sudden, Arlene Gottfried is hot.

“It takes a lifetime to be a new discovery, I guess,” she says.

Gottfried has recently been dubbed an “NYC treasure” by the Gothamist and “a quiet storm of power” by Glitterati. Britain’s Guardian newspaper has praised the “intimacy and wry humor” of her work, while the AnOther blog described her photography as a “candid and captivating ode” to New York. Last fall she had a solo exhibition at the Hardhitta Gallery in Cologne, Germany, followed by a solo show on view now at Les Douches gallery in Paris. New York’s Daniel Cooney Fine Art gallery showed her street photography in a 2014 show that drew television crews and newspaper reporters from around the world and on March 3 will open another exhibition, this one featuring Gottfried's photographs of New York’s Puerto Rican community. That work was originally collected in her 2011 book Bacalaitos & Fireworks.

“They told me in Paris that there has been a lot of talk on radio and TV about the show there,” Gottfried says. “I’m happy about all the press, but it’s still a strange feeling.”

Along with the exhibitions, Gottfried is now releasing a new book, her fifth. It is called Mommie, and at first it would seem to be a departure from her previous work, which looked outward at the world of New York. Her 1999 book The Eternal Light, for instance, joyfully focused on a black gospel choir. Her 2003 book Midnight told the story of a man with schizophrenia. Her street photography was collected in the 2008 book Sometimes Overwhelming, which was followed by Bacalaitos & Fireworks.

Mommie, by contrast, is a portrait of three generations of women in Gottfried’s own family — her grandmother, mother and sister. It is an intensely intimate collection of pictures taken over several decades following the women through their lives together and through their separation by illness and death.

“As they aged, I started to photograph them more, my grandmother and my mother, to try to hold on to them,” Gottfried says. “I was trying to stop time, but obviously I couldn’t.”

The photographs in the book are certainly more personal than any that Gottfried has published before. “Just before the book came out, I looked at it, and I was a little nervous about how revealing it is,” she says. On the other hand, what she did throughout those years of photographing her family was not all that different from what she has always done, which is to capture on film the people New York, and through them the character of the city, with impeccable authenticity.

“Doing this was just part of everything I was doing as a photographer,” she says. “I didn’t really think of taking these pictures as a project. It was just the way I usually work. Things that are near me, things that interest me, I photograph.”

A Saint of New York

Gottfried’s new popularity falls in line with today’s interest in a New York City that is no more. Last year the New York Times T Magazine examined the modern obsession with New York in the late ’70s and early ’80s — a time when the city was dirtier and more dangerous than today, but also less defined by corporate values of efficiency and the sanctity of wealth. New York then, wrote Edmund White, was a more democratic city, where “rich or poor, you were stuck together in the misery (and the freedom) of the place.”

“Arlene Gottfried is one of the saints of New York City, preserving its past for future generations to see how we lived when the city was much more culturally and economically diverse,” says Paul Moakley, Deputy Director of Photography and Visual Enterprise for Time magazine. “I think she deserves all the attention that she is getting for looking at the denizens of the city that most people overlook or cast away.”

In her new book,

Gottfried includes her family, and by extension herself, in that group. She grew up with her sister, Karen, and her brother, the future comic Gilbert Gottfried, in an apartment over her father

Max’s hardware store in Coney Island, a place where there was no shortage of interesting characters to watch. Gottfried said in one interview that it was that exposure to “all kinds of

people” that helped her develop the ability to talk to strangers. Later, the family moved to Crown Heights, Brooklyn, where they lived downstairs from a troupe of dancers who performed on the Ed

Sullivan Show.

Gottfried began documenting her family just as she was inching toward a career in photography, after taking a two-year course in the basics of studio work at the Fashion Institute of Technology. After that she got a few photo-assistant jobs. “It was hard in those days; they didn’t want to hire women,” she says. “They said we couldn't do the work, that we couldn’t carry the equipment.” Later she inherited an in-house photo job at an ad agency after a number of other photographers, all men, turned it down.

Eventually she started a freelance career shooting for magazines. “I worked on a lot of different stories — a drought in Missouri, welfare moms in a hotel in New York, and one about a man who had been disabled in a car accident,” she says. “He had a monkey who helped him with his chores. That was fun.”

The Rise of Street Photography

Another reason for Gottfried’s newfound stardom may be the burgeoning interest in street photography.

“It’s a trend and interest that has developed,” agrees Gottfried. “People like looking at street photography and shooting street photography more than ever.” Her own street photography is marked by what Paul Moakley calls “tender honesty” and by a mirthful eye. Coming across a Hassidic man on a nude beach in Brooklyn is, notes Gottfried, a moment to be savored.

“When I’m lucky enough to see something like that, I feel very fortunate,” she says.

Her way of working has changed over the years, but not a great deal. “In the early days, I worked mostly with a manual Nikon, and I would often ask people if I could take their picture. But I found that sometimes people would freeze or pose, so later I started shooting more candid photos of people who were not aware of me. And that’s what I like to do now,” she says. Over the years she has shot with Nikon F2s and F3s, and also a folding 1 1/4 x 1 1/4-format camera for portraits. Today she uses a Yashica point-and-shoot. “I’m still into film,” she says.

Gottfried’s father gave her the camera that got her started — an old 35mm model that she shot with at Woodstock in 1969. She later discovered the work of Brassaï, Lisette Model and Diane Arbus, all of who she cites as influences, along with the pictures she saw in the New York Daily News, the newspaper her family subscribed to.

She is still wandering New York’s streets, but, she says, not as much as she once did. There’s a lot of photography around now, she says — perhaps too much.

“It can all cause a little dulling over,” she notes.

On the other hand, New York, though a vastly different city from the one she began photographing, can still be full of surprises. “I still have some rolls of film around that I have yet to develop,” Gottfried says. “I guess I should see what’s on them.”