Photographer Profile - David Burnett: "Photography can be a solitary business. This was a team effort"

|

|

|

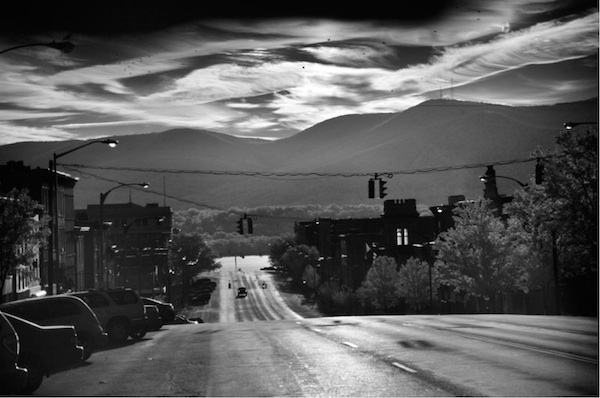

That headline, which appeared in New York magazine in 2011, tagged a once-thriving Hudson Valley city with a label that people could not easily forget. The magazine went on to note that Newburgh, about 90 miles north of New York City, “occupies one of the most dangerous four-mile stretches in the northeastern United States” thanks to gang violence and open-air drug markets.

“A lot of that has gone away. There are still issues, and still life on the street, but there are things happening in the city now,” says legendary photojournalist David Burnett, a Newburgh resident. “We’re kind of working our way towards positive outcomes rather than just negative outcomes.”

Burnett, who over a 40-year career has covered the Vietnam War, the Iranian revolution, and 10 Olympic games (among other stories), has already earned a place in photographic history. A co-founder of the Contact Press Images agency, he was named by American Photo magazine as one of the 100 most important people in photography. For many years, he lived in the Washington, D.C., area, but in 2007 he made a film in Newburgh, and his life changed. The film, called The Gefilte Fish Chronicles, was a documentary centered on the relatives of his wife, Iris, and their tradition of celebrating Passover.

After the film was completed, Burnett’s wife, who had taught communications at American University and worked in the Clinton administration, decided she’d had enough of Washington politics. “So five years ago we relocated north,” says Burnett.

Around the same time, Burnett’s life took another turn. He was contacted by Anna Wang, one of his wife’s former students, who was living in Geneva, where she worked for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Wang is also an avid photographer — she’d taken workshops with photojournalists Marcus Bleasdale in Kashmir and Gary Knight in Cambodia — and she had a proposition for Burnett.

“She said, ‘Lets get together and have our own workshop,’” he recalls.

Since then, Burnett, Wang, and a small group of professional and amateur photographers from around the globe have been teaming on a number of pop-up photo shoots and exhibitions in far-flung locations. Wang’s idea for a workshop developed into a nonprofit organization called Photographers For Hope that works with local groups on promotion and education projects.

In Rio de Janeiro, the group covered the Homeless World Cup, a soccer event run by a homeless intervention organization, and held an exhibition in Rio’s Nike store. In 2011, the photographers gathered in Bangladesh, which was celebrating its 40th anniversary, and worked with NGOs there on a variety of projects, resulting in an exhibition of prints hung on the side of pedicabs. In 2012, they were in Scotland, coaching homeless news vendors with cameras donated by Canon.

“And every time I would come back from one of these trips,” says Burnett, my relatives in Newburgh would jokingly harangue me — ‘Oh, you’ve got to go as far away as you can. Why don’t you guys do something here?’”

Which was why Burnett brought the Photographers for Hope to Newburgh in early October to photograph the city. Not the murder capital of NY. The new Newburgh.

An Intensive 10 Days

In the 19th century, Newburgh was a hub of Hudson River commerce, and the the city’s bygone glory days can still be seen in its Gilded-Age architecture. During the 1960s, Newburgh undertook an urban renewal program that New York magazine called “disastrous.” In the process, the historic waterfront was destroyed and, noted the magazine, “replaced by anything.” In recent years, however, the city has begun to turn itself around.

Burnett and his fellow photographers spent ten days working on the Newburgh photo shoot. “People arrived on a Thursday, we drove them around to show them the city, and we were photographing on Friday,” he says. “We had Anna and another woman from Geneva, an Italian guy who runs a printing shop in Croatia, another Italian guy who’s a commercial photographer in Verona, an airline captain who flies for Cathay Pacific, and a woman from Dubai. The only American in the group besides me was a guy from Philadelphia.”

Working with a grant from the Kaplan Family Foundation and another group, a local producer had planned out 30 specific events and sights for the group to photograph — a Habitat for Humanity project, for instance, and a community center for kids at the Newburgh armory. “But those plans were mostly just to provide an easy foothold for the group; they could also just go off and shoot other things that interested them,” Burnett says.

The photographers documented everything from local craftsmen and clergy to a Mexican rodeo taking place in the city. One of the photographers, Katarina Premfors, followed a cop patrolling the streets. Another, Ben Moldenhauer, photographed Chris Basso, co-founder the Newburgh Brewing Company. Sarah Bones photographed a man she saw on the street, waiting for a rainstorm to pass.

“We discovered things about the city that nobody knew anything about,” says Burnett. “I’ve lived there for few years now, but even I had my eyes opened to a couple of things.”

By the following Tuesday, the group gathered in Burnett’s Newburgh studio — located in an old handbag factory where artists create backdrops for Broadway plays — and began editing. “It looked like Photojournalism 101 class, with everyone working way into the night,” Burnett says. By the next Friday, the edit was down to 100 pictures. “Then our Italian printer took over,” says Burnett. “Canon had leant us a beautiful new 24-inch printer, and we started cranking out these 17 x 22-inch prints.”

On Saturday, the prints were up on the wall at the local armory for a opening-night exhibition. “And a crowd came unlike you ever get in Newburgh, because it was people from the street, people from the ministry, and people from the upper end of society,” says Burnett.

Anna Wang later wrote that the experience of capturing Newburgh’s revival “was like falling in love with our eyes open. It was intense.”

A Solitary Profession

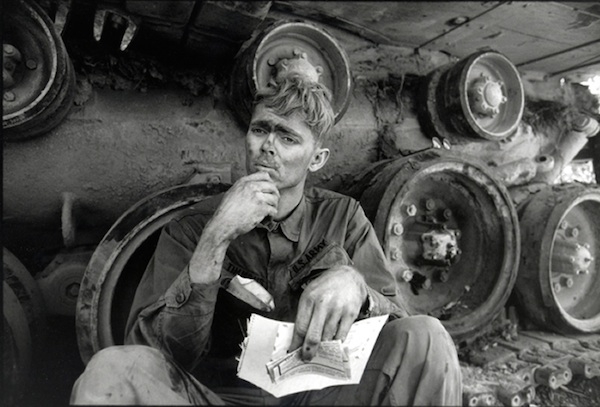

Burnett started his career as a freelancer after graduating from Colorado College in 1968, shooting for Time and Life. In Vietnam, he photographed Khe Sanh and was present at Trng Bàng in Tây Ninh Province the day that another photographer, Nick Ut, shot his iconic picture of nine-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phúc fleeing a napalm attack. Burnett produced an iconic image of his own in Vietnam — a unforgettable photo of an American soldier holding a letter from home.

His images from inside the Iranian revolution, including a famous portrait of Ayatollah Khomeini, was a journalistic coup. He covered the Ethiopian refugee crisis and political upheaval in Chile, balancing the calamities with other kinds of stories. In 2009 he published the book Soul Rebel: An Intimate Portrait of Bob Marley. His photos of the Olympics, often made using an antique Speed Graphic camera — has been widely praised.

The work he’s been doing with the Photographer’s For Hope group — if work is the right word — is something new for Burnett.

“Photography can be a very solitary business. In photojournalism you often work alone or with just a writer,” he says. “And with digital cameras, email and WiFi, it’s become more and more of a solitary activity. The projects we do with Photographers For Hope is an absolute team effort. We all enjoy the camaraderie and sharing pictures with one another in the evening. Nobody’s afraid to say, ‘We love you but your picture sucks.’ People are warm in dealing with each other. You don’t get many experiences like that over the course of the year.”

Perhaps photography is actually becoming less and less a solitary activity. Recent years have seen a boom in workshops, master classes and team projects focusing on specific social issues and communities, as well as the rise of photo collectives. Photographers For Hope may represent a new direction for the medium in an era of global connectedness.

“We’re trying to do something that is not just having fun with photography, but also trying to use the power of photography for positive purpose,” Burnett says.

The exhibition that Photographers For Hope shot in Newburgh is on view during weekends through December in a storefront space at Grant Street and Broadway, one of the busier intersections of the city.

___________________________________________________________________________

Credits, top to bottom: Ben Moldenhauer;

David Burnett; Sarah Bones; Ben Moldenhauer; Katarina Premfors; David Burnett