Photographer Profile - Doug Menuez: "We're looking at a whole new model now"

|

|

|

It was 30 years ago that Menuez, who as a young freelancer had already covered the AIDS crisis, the war on drugs and other big stories of the day, began documenting the digital revolution beginning to take shape in California. He had just returned from covering the famine that devastated Ethiopia and Eritrea and was looking for a different kind of tale to tell.

“I was discouraged about whether my work had really contributed to helping people in a meaningful way, so I wanted to tell a positive story,” he says.

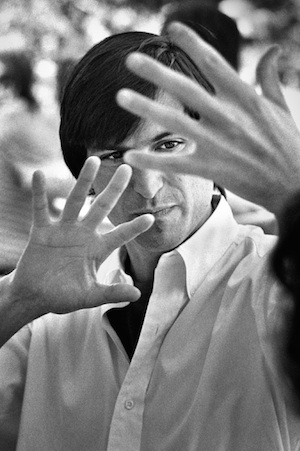

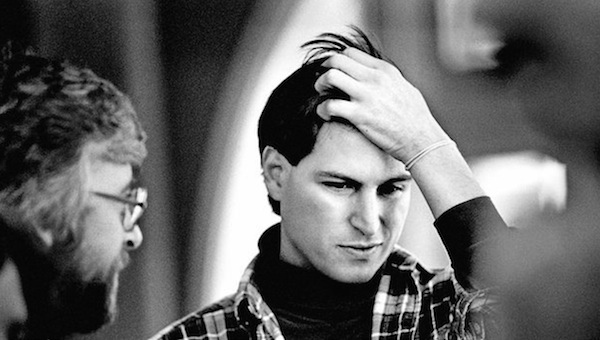

Living in the San Francisco Bay Area at the time, he didn’t look far: Menuez turned his attention to Jobs, who had just been forced out of Apple, the company he’d helped create, and was at work on a new startup called NeXT. He had promised to build a computer that would revolutionize education. “And that idea really excited me,” says Menuez.

Jobs, who Menuez has called “the consummate showman,” ended up giving the photographer intimate access to himself and the work being done. Menuez then approached Life magazine with the idea for a story framed as Jobs’s comeback. The magazine gave him an open-ended three-year assignment.

That was what the photojournalism business model was like 30 years ago.

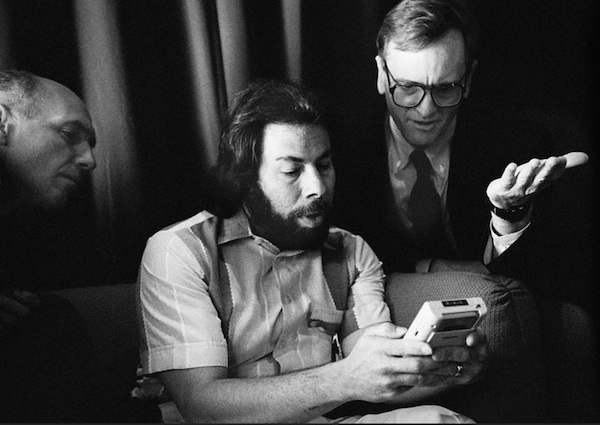

The three-year assignment turned into a 15-year personal project that went well beyond the original idea. Working on and off between other assignments, Menuez went on to record a crucial period of American history from the inside. “I shot everyone from Bill Gates to the financiers like John Doerr who made it happen,” he says.

He was on hand at Adobe when Photoshop was created — he documented the work on Kodak Tri-X film — and witnessed the birth of Netscape and the rise of the Internet, as well as Jeff Bezos’s retailing behemoth, Amazon.com.

Menuez ended the work in 2000, when the dot com bubble burst and the nature of Silicon Valley changed. “It shifted from being this noble cause of making the world a better place to being an unsustainable greed-fueled gold rush. And it was just no longer interesting,” he says. He went onto other documentary projects and a string of more lucrative commercial jobs that helped pay for them.

In the meantime, his Silicon Valley work more or less fell through the seat cushions of history. No one, it seemed, cared much about the history of those early years of the Silicon Valley. Eventually, Stanford University acquired the archive of 250,000 negatives, and photo editor Karen Mullarkey was brought in to edit the material.

“Then they came back to me a few years later and said, ‘Our budget has been cut and we can’t afford to scan this stuff.’ So I got back involved in 2009 and raised some money and then used my own savings to edit and scan the material,” Menuez says.

It was after Jobs’s death that interest in Silicon Valley’s shatteringly innovative years — and Menuez’s work — really sparked. An exhibition of the work debuted at the Moscow Photobiennale in 2012, followed by a show at the Visa Pour l’Image photojournalism festival and other venues around the globe.

“I couldn’t really get arrested with this project in the Untied states, but for some reason people elsewhere thought it was wild,” says Menuez.

Last year, however, Menuez published the book Fearless Genius: The Digital Revolution in Silicon Valley 1985-2000, and he recently showed the work at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California, in the heart of Silicon Valley.

“That was kind of an acid test, because the people in the pictures were going to be able to show up and tell me what they really thought. But they loved it. It set attendance records,” Menuez says.

The renewed interest in the work has sent Menuez on a new mission. Now he himself is innovating new ways to use the archive to fulfill the purpose he originally intended for it. He wants it to make a difference.

“So we’re looking at a whole new model now,” he says.

Interactive Innovation

Menuez was born in Texas, but when he was young his family moved to the South Side of Chicago, where his father worked with community organizer Saul Alinsky. Most of his youth, however, was spent living on Long Island. “So I consider myself a New Yorker,” he says. At age 10 he was given an Argus C3 rangefinder, and by 12 he’d built himself a darkroom and was beginning to make trips into New York City to shoot street scenes. Later he began photographing anti-war demonstrations. After attending the San Francisco Art Institute and studying photojournalism at San Francisco State University, he interned at the Washington Post.

“And within a couple of years I was a freelancer shooting for Fortune and Life magazines,” he says.

It was in the 1990s, right in the middle of his long project on the Silicon Valley, that Menuez began taking on commercial jobs to support the documentary work. Over the years, he’s shot projects for Charles Schwab, General Electric and other companies. He recently returned from Asia, where he completed a documentary project for FedEx.

At the same time, he has been experimenting with new ways to, as he puts it, “keep the Silicon Valley project relevant.”

“We’re trying to figure out how we can we make 'Fearless Genius' more than a book or exhibition," he says.

He has, for instance, launched an education program and is working on an interactive web platform, and on a program of leadership conferences for entrepreneurs. He recently found success by publishing work from “Fearless Genius” at Storehouse, one of the new generation of self-publishing websites that are transforming the way photographers are getting their work seen. “I ended up with 90,000 followers on the site,” he says.

“Today, a work like ‘Fearless Genius’ has to be more than the sum of its parts,” noted David Schloss in a recent story about Menuez at Digital Photo Pro. In the story, Menuez says that he is trying to use the tools created in the Silicon Valley to expand on his project.

“I am trying to create, trying to take this record I have and make it a compelling educational or entertainment body of work. We're trying to make a new model—we have a core story and then a documentary around it, a book and an exhibit. We're combining video and sound around the stills, but all of these expressions of the core story get distributed to different channels and different revenue streams.”

The passage of time has allowed Menuez to view the history he captured in the Silicon Valley in a new way and to tell his story in new ways. “My project isn’t definitive — it’s my view as a wandering observer, a witness. And now I can look back and add opinions. I can draw conclusions and make comparisons to today,” he says.

That opportunity is what’s driving him forward. “The people I photographed defined their lives by their mission.They sacrificed everything to make something that no one had done, and they actually did want to improve human life,” he says. He wants his pictures of that time to inspire future fearless geniuses to do the same.