Photographer Profile - Robert Clark: "I've worked with some of the smartest people in the world"

|

|

|

Clark reached out to an animal

trainer—the man who trained the wolves for the film Dances With Wolves—and explained his predicament. It so happened that one of the trainer’s wolves was about to give birth

to cubs, and one of his dogs, a Maltese, would soon be having puppies. The trainer took a cub and puppy from the two litters and raised them together for a year.

After waiting 12 months, Clark was able to photograph the perfectly amiable animals together. “That’s the kind of photo that only Geographic would do,” Clark says.

“Most other magazines need their photos next week, not next year.”

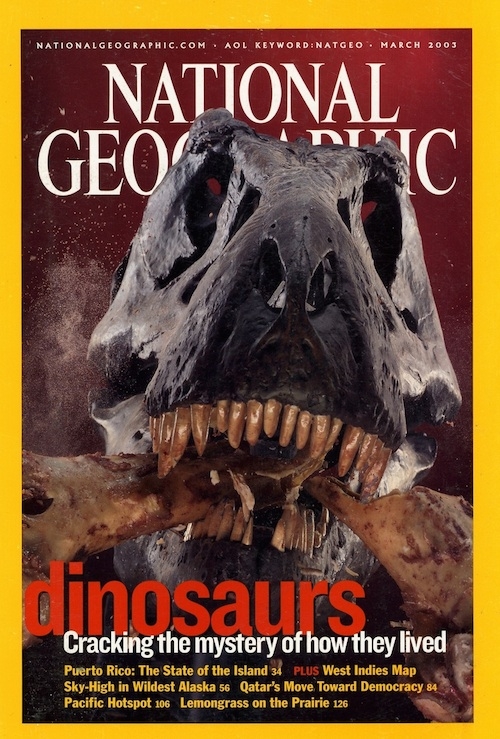

As it turned out, Clark’s picture of the wolf and dog became his first cover for the US edition of Geographic; he’s since shot 11 others, and 40 stories overall, for the magazine. “I’m not sure where that puts me on the quote-unquote all-time list, but it’s a lot,” he says. “I think that over the past 20 years I’ve turned down only two stories they offered me.”

The scope of his output became clear to Clark only two years ago, when he began thinking about collecting his Geographic work in a book. Looking through his stories, he saw a thread linking them together—in one way or another, many focused on the science of evolution. With that idea in mind, he created an accordion-style dummy that pulled out into a visual narrative that literally linked his work together.

Clark presented the dummy to publishers at the Paris

Book Fair in 2013 and, as he puts it, “was told 15 times that it was a great idea but that nobody would ever be able to do it.” Later, he showed it to Phaidon Press. “The editor

there said, ‘Yes, I think we should do this book,’” says Clark, “and I said, ‘Yes, I think so too.’”

He is now about to

launch a Kickstarter campaign to crowdfund the project. “I’m hoping I can raise $40,000 to $50,000—I’ve got 377,000 followers on Instagram, and the connection with National

Geographic will help,” he says. “It’s amazing to see how you can build your own audience, and I’m very interested in doing that.”

Evolution of a Photographer

Some photographers aim their careers in a particular direction with certain goals in mind; others start taking pictures and see where they end up. Clark is among the latter group.

“My uncle used to say that you need to ride the horse in the direction it’s going,” he says. “You can learn a lot that way, not fighting things in a sense. I’m lucky in the work I’ve done; I’ve worked with some of the smartest people in the world.”

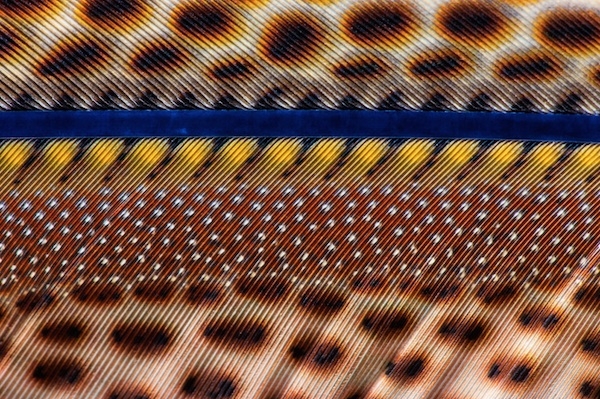

Clark has shot Geographic stories about everything from Mount Vesuvius and the history of taxidermy to the latest research on dinosaurs, the human predilection for sugar and the evolutionary biology of bird feathers.

That story, published in 2011, was one of his most memorable, and an excellent example of the type of documentary science photography he has mastered.

“I was starting to work on the story and went to talk to Rick Prum, an ornithologist at Yale who was leading the charge in saying that birds and dinosaurs are related,” recalls Clark. "He developed a technique to inject color into fossils so that he could accurately show the feathers of birds from the past.”

Clark’s images manage to be shatteringly beautiful while forming an evidentiary archive for Prum’s ideas; they will be published as a book this fall by Chronicle Books in a prelude of sorts to his Phaidon retrospective.

“The best part for me about the work I do is that it gives me a chance to dive into the information, and from the information comes approaches to the photography,” says Clark. “The most important thing is to make sure you know what you’re talking about. You do the research, find out who’s got the great feather collections, and then go see the feathers.”

Taking pictures of feathers – or working on science stories at all — was not what Clark thought he’d be doing when he was growing up in western Kansas. He says he started thinking about photography after reading a book about the great Kansas miler Jim Ryun. The book included photos by Sports Illustrated contributor Rich Clarkson, who, Clark later discovered, lived in Topeka. “To me, that was proof that someone from Kansas could do this kind of thing,” he says.

Clark went on to study photojournalism at Kansas State University. It was another Kansan, Gary Haynes, the celebrated photo editor of the Philadelphia Inquirer, who arranged for him to come to the newspaper, at first as an intern and then a regular contributor. At the time, in the mid-1980s, Haynes was turning the Inquirer photo department into a hotbed of talent, with a staff that included Larry Price, Sarah Leen, and Stephen Shames.

While he was at the Inquirer, Clark met someone else—Pulitzer Prize-winning writer H.G. (Buzz) Bissinger, who had just gotten a contract to write a book about the football team of Permian High School in Odessa, Texas. Clark convinced Bissinger to hire him as the photographer of the book, which became the best-seller Friday Night Lights.

Recently, Clark revisited that part of his past: To mark the 25th anniversary of the seminal book, which spawned both a feature film and television series, Sports Illustrated sent Clark back to Odessa to re-create his original cover photo with the three Permian players who were on it.

An Unintended Specialty

Clark’s big break came in 1990s, after he moved to New York and began freelancing for magazines. By that time, he’d assisted for a number of master photographers, including Walter Iooss, Gregory Heisler and Craig Cutler. “And because of that,” he says, “I knew how to light big objects.” One day he decided to phone Tom Kennedy, then the director of photography at National Geographic. Kennedy had been a photo editor at the Philadelphia Inquirer during Clark’s stint there and knew his work. The result was Clark’s first story for the magazine, about the discovery of 17th-century French explorer Robert de La Salle’s sunken ship in the Gulf of Mexico. That project was followed by a story about Patagonian dinosaur hunters.

In that way, Clark began to fill niche at the magazine that, he says, nobody

else really wanted to fill. “What I really dreamed of doing was to be a National Geographic photographer like William Albert Allard or David Alan Harvey,” he says. “I wanted to

wander around the world and shoot free-form narrative stories in beautiful light. But the magazine already had Allard and Harvey, and I needed to work.”

He counts among his influences Louie Psihoyos, the longtime National Geographic photographer who went on to direct The Cove (2009), an Oscar-winning documentary about the yearly killing of dolphins in Taiji, Wakayama, Japan. “He shot stories for the magazine about subjects like sleep and smell, and a lot of the jobs I got were ones he probably would have done,” Clark says.

Now, with his new book on feathers and his Phaidon retrospective project, Clark is charting his own evolution as a photographer. “I’m not a scientist—I’m a visual storyteller,” he says. “What I do is not narrative photojournalism, but it’s documentary work. It’s all fact-based. It’s paleobotany and feathers, and that’s really, really fascinating stuff.”