Photographer Profile - James Whitlow Delano: "I show what I have seen"

|

|

|

In that sense, the timing of the Everyday Climate Change Instagram feed couldn’t be better.

Launched in January, Everyday Climate Change (#everydayclimatechange) is part of the Everyday Everywhere network of Instagram feeds that have broadened the idea of what photojournalism can be by providing a new perspective on daily life in regions around the world, from Africa and Eastern Europe to Latin America. The new feed features images by some 40 photographers from five continents who want to show that climate change is real, and that it is part of our everyday lives.

“We focus on both problems and solutions—probably more problems at this point. That’s the balance we’re at now,” says James Whitlow Delano, the Tokyo-based photojournalist who organized the project and oversees the feed. “We don’t want to water down the message, but we don’t want people to be so pessimistic that they think there’s nothing they can do about the problem.”

Delano, who has been covering stories related to the environment and social change throughout Asia, Africa and Latin America for the past two decades, had already been considering setting up an Instagram feed focused on climate change issues when, last summer, he took note of the Everyday Africa feed established by photographer Peter DiCampo, which offered a fuller view of life there than is often seen in the media. Delano wondered if the concept of Everyday Africa and the similar feeds it spawned around the world could be expanded to include a photo stream anchored in science. Last October, he met with DiCampo in New York to discuss the idea.

At the time, DiCampo was meeting with a number of photographers who had launched Everyday sites, and a loose-knit organization was created in order to maintain a degree of control over the brand’s identity and mission. The pliable Everyday concept had already been pushed to include feeds like Everyday Black America and Everyday Incarceration, which added elements of issue-based content to the mix, and the idea of Everyday Climate Change went further.

“It was clearly a leap from what we had been doing,” says DiCampo. “But it seemed clear that it fit in with what we are about. It’s geographically diverse, and while it’s fact-based, it’s not, ‘Here’s climate change—look at these melting ice caps.’ It’s very much about daily life.”

Mainstreaming Climate Change

For Delano, Everyday Climate Change is a way to talk about what he’s been witnessing around the globe in a way that reaches beyond what he calls the “cloistered photo world.”

“I wanted to communicate with people in mainstream media and establish connections between our actions in the mostly industrialized north with what’s happening on the other side of the supply chain,” he says.

From his perspective, what’s happened is that people in countries like the US have developed a false sense of security about environmental issues. “A lot of our manufacturing has been exported, so the mess is gone—people don’t see it on a day-to-day basis,” he says. “But a lot of that mess has been sent over here to Asia.” He points to the dangerously polluted air of cities in China, hazy with coal smoke, as an aspect of the global nature of climate change. “I’ve seen things in Asia that scare me,” he says.

At the Huffington Post, Delano recently related a story about the Batek Negritos, hunter-gatherers he photographed in 2010 and 2011 after they had been relocated away from their ancestral rainforest home by the Malaysian government. The land they once lived on has been logged and turned into palm oil plantations.

Loss of rainforest contributes to a rise in the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, a factor in climate change. Moreover, Delano pointed out in his article, the environmental impact is inextricably linked with social and human-rights issues.

“I do not believe that humans will die out entirely from climate change,” Delano wrote, “but many endangered species will [and] many people will needlessly suffer grinding poverty as a result of global warning, and many will also die as a direct result of that poverty.”

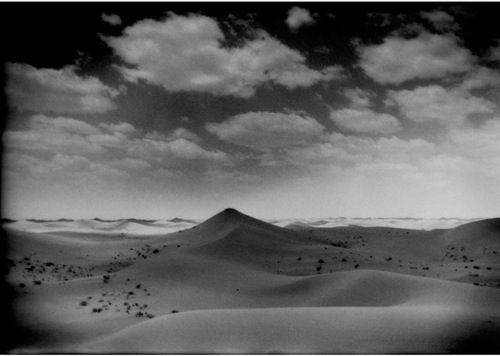

One of big challenges facing Delano and the other Everyday Climate Change contributors is how to picture the effects of climate change on a daily basis. “Because we don’t always live in the places where climate change is visible—in the margins, in the deserts or the arctic or the rainforests—we have to travel to these places,” he says. Consequently, there is a considerable amount of what Delano calls “later grams” on the account—images drawn from photographers’ archives.

Cultural differences also play a part in how the feed’s various photographers approach the topic, says Los Angeles-based photographer Sara Terry, an Everyday Climate Change contributor.

“I see my place in Everyday Climate Change as being very different from what most of the other photographers are doing,” she says. “While they are reporting from places that might seem remote to most Americans, I’m reporting from California, and the approach to talking about climate change in the US has to be more nuanced. Most people think of climate change and picture an island in the Pacific going underwater. But I’m showing how it’s there in your backyard.”

She means that quite literally: Recently, Terry shot a story about an artificial lawn in Los Angeles. “In my caption, I noted how much water it takes for a real lawn. We’re in a drought here in California, which is not caused by climate change but is exacerbated by it, and it’s important to show not only that it exists, but that concrete steps—big and little—can be taken as solutions.”

Everyday Climate Change gives its contributors a new template for communicating directly with a concerned audience—the feed has 15,000 followers so far—and as such it indicates how journalism, enabled by social media, is evolving. But along with that new power to communicate comes responsibility. Because it’s a fact-based photo feed, captions are a particularly important.

“The photographers have to be smart, and all their captions should be able to be fact checked,” Delano says. “It makes you think about what you’re saying, whether you’re saying it properly. I always ask myself, ‘Is a scientist going to get on my case if I overstate something?’ It’s good to have to be careful how you frame a situation.”

The Loss of a Forest

It was shortly after moving to Tokyo from Los Angeles in 1994 that Delano began focusing on environmental issues in his work. He’d just read a 1987 book about the virgin forest in the heart of Borneo and went there to see it for himself. But the forest had disappeared. “I realized then how modern technology could lay to waste huge swaths of land,” he says.

Delano moved to Tokyo after talking to a friend who had just returned from Japan. He was living in Los Angeles at the time, launching a commercial photo career after having worked as an assistant for Annie Leibovitz, Michel Comte and Joel Meyerowitz, and saw Japan as a place where he could redefine himself as an artist.

“I thought about how Robert Frank came from Switzerland to America saw it in a new way, and pictured myself doing that in Japan,” he says. He learned to love the country—and a Japanese woman who is now his wife—but after two decades he knows that he is still considered an outsider. “I found from day one that assimilation is off the table,” he says.

He was in Italy on March 11, 2011, when a magnitude-9 earthquake off the north coast of Japan caused a tsunami that left more than 28,000 dead or missing. He flew back the next day, gathered together some journalist friends in Tokyo and drove north. “It was a time of unreality here,” he says. His widely praised images of the disaster were later gathered together in the book Black Tsunami, which was crowdfunded and published by FotoEvidence. Work from the series was also selected for the American Photography 30 annual.

As he has turned his attention toward climate change, Delano has found his adopted homeland to be an interesting vantage point, because in Japan conservation is an everyday issue. Per person, he notes, Japanese consume about half the carbon that Americans do. One of the images he recently posted at Everyday Climate Change shows a parking lot in Tokyo’s Setagaya Ku (Ward) filled not with cars, but bicycles.

“People ride bikes here. They don’t mind being crowded into trains. And they don’t heat all the rooms in their houses—just those where they’re sitting,” he says. “That’s why Japan came up with heated toilet seats—the bathrooms are really cold.”

Science doesn’t get any more everyday than that.

Delano already has plans for developing Everyday Climate Change—he wants to add mind maps—a visual tool that makes complex information more comprehensible—to show the cause and effect of climate change in various localities around the globe. He’s also planning to take the project to universities and schools around the US, which is another logical extension of the Everyday concept.

He’s driven by a sense of mission. “I show what I have seen … in the magnitude and proportion I have seen it. It is what it is,” Delano wrote at the Huffington Post. “The magnitude of the problem needs to seen, without filters, for the true challenge to be understood. Solutions and change, that is real change.”