Studio Visit with Nick Lamia

Peggy Roalf: My first impression of your current exhibition, Cloud Architecture, seen from the entrance of Planthouse Gallery, was: This is so much like what you did at Wave Hill, back in 2012. You had done drawings of dead bumble bees, all on small sheets of paper, pinned to the wall in a grid. I remember asking why dead bees interested you as a subject for art, and you saying that live bees moved so fast that when we think we are drawing them, we are just recording what we think we have remembered—not the actuality of the bees.

Nick Lamia: That’s true, and there was also a conceptual reason for the dead bees. As you know, I was involved in ecology earlier in my life and I’m very interested in the relationship between society and nature. Bees were, and are an Indicator Species, like a canary in the global coal mine. Those watercolors of dead bees were meant to be a catalyst for conversations around global environmental health. But that’s a digression. Your remark was really about the possibility, or impossibility of capturing a likeness through drawing.

It's true that for me it feels impossible to capture a likeness of something that moves as quickly as a bee. And I thought clouds would move slowly enough that it would be easier to draw them accurately from observation. In my experience though, as clouds cross the sky, they morph and evolve constantly in a way that makes it impossible for me to accurately draw them from observation. I am forced to settle for a series of approximations that might approach their actual appearance but will never be true to a single moment in the cloud’s existence.

Peggy: So now I ask: What is there about clouds that caused you to make some 70 cloud drawings---and what is there about clouds that you find to be architectural?

Nick: I didn’t set out specifically to make 70 drawings. I happened to have a drawing pad that had special significance to me and I decided to use it in its entirety for this series and it ended up having 70 sheets on it.

As for the “architecture” of clouds, I started to work with the idea of cloud forms after a recent show titled “Cloud, Mountain, Valley, Sea.” Each of those objects symbolized a portion of the cyclical movement of water through Earth’s biosphere: water vapor rises off the ocean and forms clouds; then condenses and falls onto mountains; flows through river valleys; and eventually back to the sea again. Each painting in that show was abstract, but their compositions and imagery were inspired by what I think of as the underlying forms of those four iconic parts of the cycle.

But in that series, the clouds got short shrift—almost none of the pieces in the show related to clouds because I hadn’t yet found a way to evoke cloud forms using my abstract vocabulary. At least not in a way that satisfied me. So, after the show, I began experimenting with different ways to explore cloud forms.

Peggy: I understand from what you said in the gallery that the series began before you moved your family from the city up to rural Westchester, in 2020.

Peggy: So these are all from remembered features about cloud behavior. Could you talk a bit about how drawing from memory differs from drawing from observation.

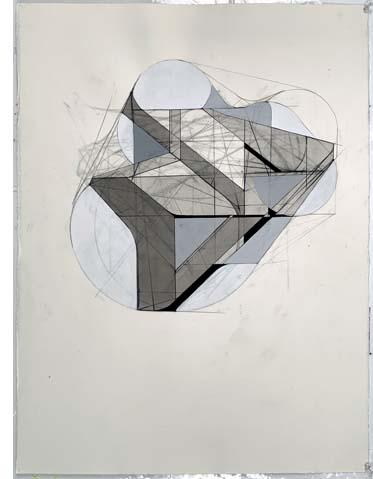

Nick: In a sense all drawing is from memory. You look at an object, take note of some feature, then look at the drawing to make the next mark. In the interim between observation and mark your memory of the object is informed by intuitive associations and connections as well as all the life experience in your head. No mark can replicate the object exactly—and this is where the magic is for me. In these drawings, I intentionally amplified the part of the process where my intuition is involved and allowed that to take precedence over any need to illustrate the “real” appearance of clouds.

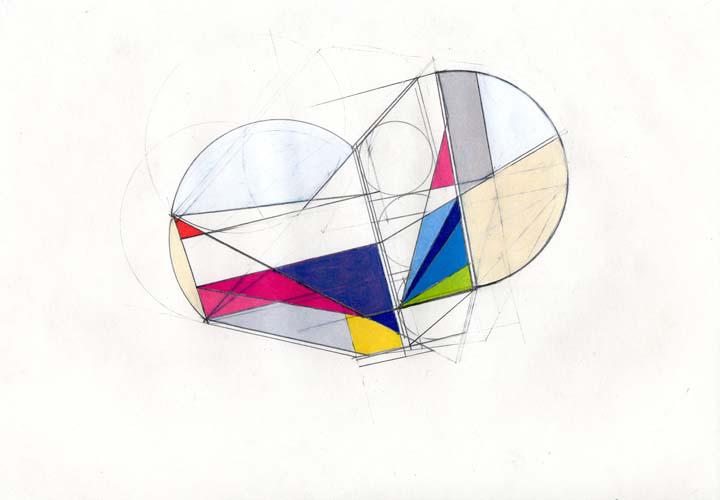

Peggy: You mentioned when we met in the gallery that the qualities of clouds changing and morphing so quickly into new forms caused you to look at them differently—almost as if these drawings became a kind of cubism in the way you found architectural form in their rapidly changing shapes, within the apparent softness of their fleeting forms.

Nick: Yes, when drawing a moving and changing object like a cloud, the subject of the drawing appears different with each glance. This constant evolution can be frustrating but also liberating, in the sense that the constant evolution of clouds prevents a specific capturing of shape, but also gives the artist permission to apply their own impulsivity, intellect and instinct to the image and therefore to create something that is, in my view, much more than a representation of the object.

All of that said, I think it is a cop-out to say the drawings are “whatever you want them to be.” I aim to give them a specificity that makes the viewer feel a sense of recognition, without being able to name exactly what they recognize. Philip Guston spoke about this. He called it the “specific enigma” and he said he strove to create imagery that had a quality of recognition but that went beyond reality. Another way one might think about this is to think of these abstract images as if they depict things that exist in a place which is real, but beyond our ability to fully perceive. Like ultra-violet light, we know it exists, but it is just outside our range of perception so we can’t really put a finger on what it “looks like.”

Peggy: What about the specificity you find while drawing cloud structures—and how that specificity informs the paintings you began following this series of drawing?

Nick: In using the relatively simple materials and approach, not to mention the constant background presence of the idea of clouds, it would be easy to fall into the trap of making the same picture over and over again. To avoid that, I aim for each drawing to have its own, what I think of as, “personality.” Each image must be specific to the point that one can perceive its character in contrast to the other drawings in the series. For instance, if I chose two drawings at random from the group and asked you to tell me which one is louder and which quieter, I want the answer to be obvious. Better yet, if we chose some drawings, showed them to a group of people and asked them to match the images to a set of characteristics, say “awkward,” “silly,” “confused” and “violent,” I would feel successful in having achieved this specificity I’m after if there was clear consensus among the group as to which drawings matched which characteristics.

As a student I was told never to just draw an object in the middle of the page, that you must always provide some context. I specifically remember one instructor saying you shouldn’t make your drawings like images of a “specimen on a petri dish.” But it’s my natural tendency in drawing, as opposed to painting, to focus on a specific object, and to zero in on it to the exclusion of other things. I enjoy narrowing my attention, and the viewer’s, on one thing, like the bees we talked about earlier, like a series of highly realistic drawings of tree stumps I know you’ve also seen, and like these “clouds.” Perhaps that makes my drawings (and perhaps drawing in general?) more cerebral while the paintings are more environmental in the sense that they, even the abstract ones, are like whole worlds that can extend off the edges of the canvas.

Peggy: You chose simple materials to make this suite of 70 drawings. Could you talk a bit about your fundamental connection to the pencil and why you felt desk pencils and waxy colored pencils and eraser are the right tools for this work?

While I was working on these “Cloud Architecture” drawings, I realized, with joy, that my memory of the feel of [the Crayola crayons I used with newsprint coloring books as a kid] is akin to the way my colored pencils feel today. In both cases, the pigment can be built gradually from almost imperceptible veils to a thick layer that sits, skin-like, atop the paper. It was wonderful to experience again the simple pleasure of applying waxy color to paper—multiple times while drawing these pictures I felt a strong connection to my childhood self, re-living the joy of placing pigment on paper—without judgment, without preconception and with a sense of simply allowing an image to unfold through an intuitive, trusting process of mark-making. This experience proves to me the importance of maintaining that open, innocent, non-judgmental wisdom that exists in all of us as children but is difficult to describe and to recapture. Perhaps this is what Picasso was referring to when he talked about trying to see the world through a child’s eyes as an important part of his creative process.

Nick: Pollock famously responded to the question of how one knows when a painting is finished by asking, “How do you know when you are finished having sex?” His response was colorful and provocative: classic Pollock. And he was correct; there is something orgasmic about “finishing” an artwork, but I don’t believe it’s quite so simple.

In my view, artworks don’t have a necessary ending point beyond which no more alteration can or should be carried out. One can bring an image to a satisfying point of resolution and then continue past that point, altering the image and necessitating further development to get it to another, new place where the image is resolved again in a different way. This is how these drawings came to be, actually. During the course of this series, because of the process of making marks and then erasing them and making more marks and then erasing those too, and so on, I began to feel that these images might never necessarily be finished in a conventional sense. Rather, each of them came to a point in their evolution when I decided to stop working on them. So, to return to your original question, artworks can and should be brought to a point of resolution, but they are never necessarily “finished” in a conventional sense.

I think of this process as an adventure through unknown territory and each stage of the work is like a new vista, where a new horizon becomes visible, with the promise of new discovery. It is my job, and great pleasure, to seek and find, through drawing, imagery of particular vitality and at some special point, to let it be and begin a new adventure on a new sheet of paper. Each time I stop working on an image it is because I perceive an unquestionable entity, an ineffable but specific wholeness that compels me to make it permanent by leaving it alone.

There will be a reception on March 31st from 6:00-8:00 pm for Nick Lamia | Cloud Architecture, at Planthouse Gallery, 55 West 2th Street, NY, NY The exhibition continues through April 9th. Info

NICK LAMIA (b. 1971) Born in Santa Monica, CA. Lamia currently lives in New York City. He is an award-winning artist whose work includes drawing, painting, printmaking, installation, and sculpture. He is the recipient of a Guggenheim fellowship and residencies at Wave Hill, The MacDowell Colony, the Robert Blackburn Print Workshop, and the Triangle Artists Association. In addition, 500 of his small-scale drawings were included in the inaugural Bronx Museum Biennial in 2011. Recent solo exhibitions include Cloud, Mountain, Valley, Sea at Jason McCoy Gallery in New York and Greenhouse, for which he created a group of site-specific wall works for the Richard Meier building at Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn.

Website: http://www.nicklamia.com

Instagram: @nick_lamia_studio

DARTinterview