Frank Stella and Moby-Dick

Frank Stella, whose work is currently the subject of a major retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, hit the New York Art world running, in 1959, with a series known as the Black Paintings. In these 24 pieces, which he diagrammed in advance of picking up a brush, he studied the effects of black house paint on raw canvas, applied in symmetrical linear bands delineated by stripes of blank canvas.

The series began with the simplest possible combinations, gradually reaching a crescendo, as if portraying a musical set of themes and variations in a sublimely systematic way. With this radical new form of abstraction, Stella ushered in Minimalism. He said, "What you see is what you see" and went on to prove that geometric form and color could rise beyond decoration to reach the highest level of art-making.

For a while, his approach seemed almost scientific, as he defined painting as an opportunity to solve artistic problems by painting through a series of issues to reach a conclusion about painting that could be stated visually and literally. The critic Lawrence Alloway came up with the term "systemic art", referring to geometric abstractions by Stella, and his contemporaries Agnes Martin and Kenneth Nolan, among others.

By the late 1960s, Stella had begun to paint geometric compositions on aluminum panels, the corners of which he notched out to create shaped paintings that began to blur the line between painting and sculpture. "A sculpture," he said, "is just a painting cut out and stood up somewhere."

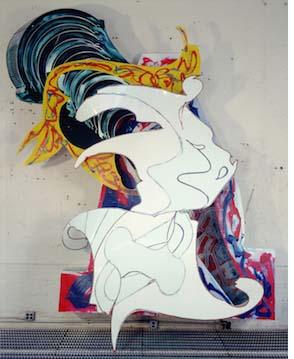

Operating like Matisse did when making his cut-outs, but using metal and industrial tools instead of paper and scissors, Stella sawed, hammered, and welded his vocabulary of aluminum forms into shape, then attacked every surface, front and back, with thick layers of paint, piled up, scraped away, sometimes wiped off, that re-delineated these riotous assemblages in a way that seems to resolve the visual cacophony of the chaotic overlapping planes he had created.

This week, several pieces from Stella's Moby-Dick series meet their inspiration when the third annual Moby-Dick Marathon Reading will take place in the Whitney's fifth-floor galleries, where the exhibition is installed. Artists and writers will read Melville's epic novel, starting at 11 am on Friday, November 13, and conclude sometime on Saturday, November 14--the 164th anniversary of the publication of Melville's masterpiece. The event is free, with museum admission.

Above, left: Frank Stella, The Whiteness of the Whale (IRS-1, 2X), 1987. Paint on aluminum. © 2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Steven Sloman, courtesy the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Frank Stella | A Retrospective. Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort Street, NY, NY. Info Moby-Dick: A Marathon Reading Info