Edward S. Curtis: The Shadowcatcher

Timothy Egan’s new book, Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher: The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2012), tells of the epic undertaking of the photographer who documented Native American life.

Mr. Egan is a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer for The New York Times, who won a National Book Award for his book about the Dust Bowl, The Worst Hard Times. In a recent feature for the New York Times LensBlog, Timothy Egan wrote,

I’m a third-generation Westerner, so the photographs of Edward S. Curtis have been as much a part of my landscape as a desert mesa or a mountain glacier. I took him for granted: those faces of Native Americans, those everyday tasks, those searing looks from the inside of tepees lit by late daylight. In his pictures, ordinary people look extraordinary. He captured the humanity of the continent’s first inhabitants.

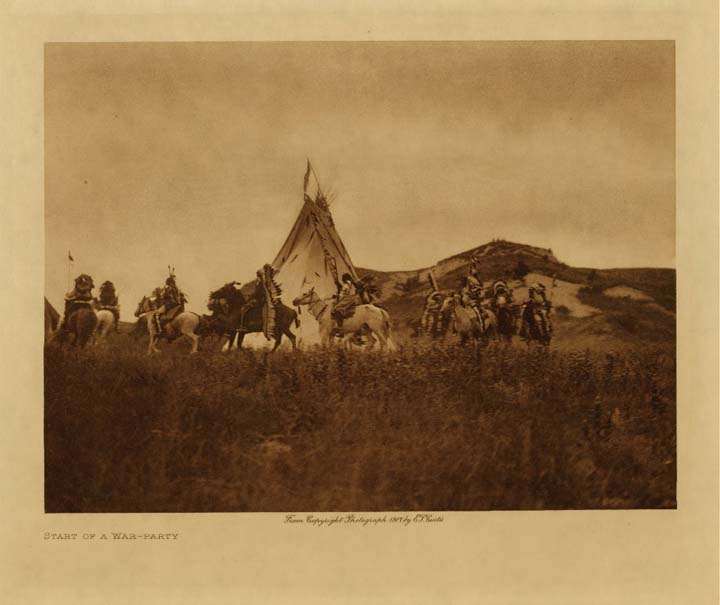

Edward S. Curtis, Start of a War Party, 1907, from The North American Indians, Volume 03, The Teton Sioux, The Yanktonai, The Assiniboin [Seattle]. Cambridge, Mass.: The University Press, 1908. Courtesy Northwestern University Digital Library Collections.

But it was only when I started looking at his life story for my book Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher — his slog by horse and hoof, train and auto to the attics and aeries of America, where Native Americans had been pushed to the margins — that I started to appreciate the scope of his masterpiece.

Curtis was a celebrity, the Annie Leibovitz of his day. He gave up a life as a prominent portrait photographer to start his Indian epic, and spent more than 30 years producing the 20 volumes of The North American Indian. It was called “the most gigantic undertaking since the making of the King James edition of the Bible” by The New York Herald.

But it was also one of the largest anthropological enterprises ever undertaken by a single man. When he started in 1896, Indians were at their low ebb, with a total population that had dwindled to less than 250,000. Many scholars thought they would disappear within a generation’s time. Curtis set out to document lifestyle, creation myths and language. He recorded more than 10,000 songs on a primitive wax cylinder, and wrote down vocabularies and pronunciation guides for 75 language.

Along the way, he never denied asking people to pose. He paid them for it. He asked his subjects to dress in the clothes of their fathers and mothers. To me, this is no different than, say, going to Scotland to photograph different family clans, and then asking someone if they would pose in the kilts of their grandparents.

Curtis was looking for the authenticity that the early 20th century was crushing. He urged Indians, many of them his friends, to show him the dances and ceremonies that the government was then trying to outlaw. In essence, he was an accomplice to a crime – urging people who were not yet citizens to show him the old ways.

But Curtis achieved what he set out to do, for he always said his goal was to make American Indians live forever. Note: a complete set of The North American Indians recently sold at Swann Galleries Fall auction for $1.44 million. View the complete work online.

NOTE: In yesterday's post there is a typo in the address for Janet Borden, Inc. The opening reception on Thursday, December 6 is as follows: 6-8 pm: Mary Ellen Mark | Prom. Janet Borden Inc., 560 Broadway, NY, NY.