For 'Operators,' Pen is Mightier

These aren’t men you’d describe as approachable. Something about their mix of self-assurance, muscular build, facial hair and abundant tattoos keeps you at bay. Something around their eyes warns you off — the dull clarity in their unflinching gaze, hinting at knowledge of things best left unknown. There’s something in their movements, something calculating, something constantly measuring, something pent up, leashed, held in check. These are not men you’d like the look of, but these are the quiet professionals of Canada’s Special Operations Regiment (CSOR).

Officially CSOR is a high-readiness Special Operations Force (SOF) capable of conducting independent operations on behalf of the Government of Canada. These were the men that we sent to Libya to secure the safety of our embassy staff there in Tripoli, in 2011. These same men have been conducting operations against the Taliban since 2006, interdicting, capturing or eliminating threats to our regular forces in theater. These men are a big part of the reason that our losses here have not been higher.

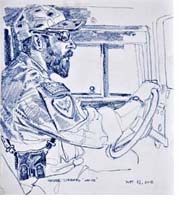

The drive out of Kabul was a security nightmare. A trio of unmarked, unimposing, but heavily armored cars travelled through the dense, thriving city along roads where every vehicle might be a threat. Disguise is important here. Blending in, essential. The threat of Vehicle-Borne Improvised Explosive Devices (VBIED) is as real as the one that killed 14 people 10 days ago. The seconds saved by this thin, urban camouflage could save your life. There are enemies looking for a target of opportunity every time Canadians venture off of a base.

The traffic in the city in the early evening is best described as challenging and dense. No rules apply. A two-lane road becomes a four-lane parking lot, before cars switch to driving into oncoming traffic. The men of CSOR stay in tight radio contact, and do their best to stay together. They watch the vehicles around — somehow hoping to spot a vehicle moving menacingly erratically in a sea of menacingly erratic vehicles. Kabul traffic surges and bumps obliviously around them. Children beg, Burka-clad women wipe dust from windows, cyclists slip by, and pedestrians lean in to stare in the car windows – looking inside through our obvious subterfuge and dust.

Master Corporal Black almost tailgates a truck full of bricks when the traffic suddenly opens up, then just as suddenly stops — during our three-car thrust across a traffic circle. Car number three almost hits us as it rockets past and becomes the number two car before we manage to extrica te ourselves from the melee. “That was f-d,” MCpl Black says, happily, as we slew back into position. “Two up” MCpl Green says calmly into the radio.

The right turn into the village of Chahar Asyab is unmarked. The dirt road through the village — lined with high-walled compounds — eventually opens out into fields, before climbing into the foothills, and arriving at the security gates and a checkpoint manned by private security guards. Almost nothing is visible in the darkness beyond the gates. “Home again,” MCpl Black says.

Camp Morehead is a small ISAF base within the considerably larger Camp Commando Afghan National Army Special Operations Command (ANASOC) base. It is built in a high valley surrounded on all sides by rolling hills, daunting mountains and abandoned Soviet tanks. Camp Commando was a Soviet Special Forces base. A huge carving of a Spetsnatz parachutist in descent is still visible, even though it was carved into a hillside almost 40 years ago. It has also been a Taliban training camp.

The mission of CSOR in Afghanistan has, since 2008 included mentoring commandos in the Afghan National Army. But when the active mission changed for our regular army in Afghanistan, the mission grew for CSOR. Their task now is to continue to mentor the training of the Afghan Commandos, but also to help create a further level of expertise in the form of an Afghan National Army Special Forces (ANA SF).

At first blush, this group of Canadian SOF operators would seem a strange fit for what is by most accounts a teaching job — and yet these men are not their stereotype. Or at least are much more than their stereotype. As well as being experts in their own field, the nature of the small SOF units in Canada has them become experts in one another’s fields as well. Many of them hold university degrees in sociology or history or political science, and even the most edgy-looking spends his down time playing 18 games of chess online at the same time. Add to this the group intellect – their five years of experience garnered while working shoulder-to-shoulder in actual warfare and you have a knowledge base that most military schools would garrote someone for.

“We have never lost anyone operationally.… We have been good, but there have been some situations where it has been pure luck,” said Warrant Officer (WO) Pink, the CSOR Team Second in Command (2IC).

WO Pink was born in British Columbia, raised in Winnipeg and now lives in Ontario with his wife and three daughters. His eldest is going to be an artist when she grows up.

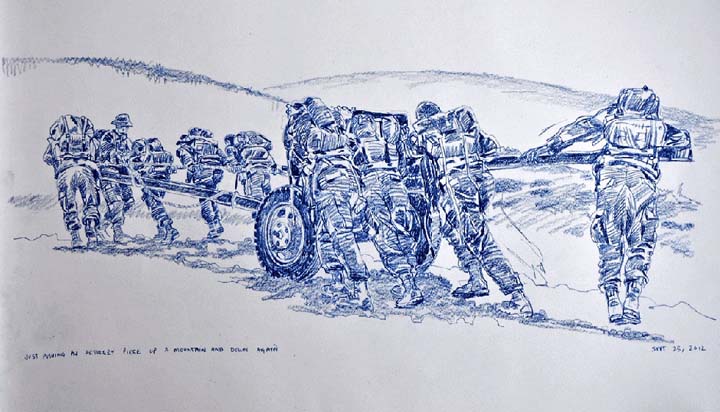

The first challenge for those hoping to become an ANA SF soldier takes previously qualified ANA commandos through a series of grueling physical tasks, over a period of three days. The hopefuls are forced to carry a backpack filled with 50 pounds of rocks. In one such test, an ancient artillery piece (see art at top) must be rolled almost a kilometer to the top of the nearest Ghar— and back down again — by a team of 16. In another a 200-pound log must be carried between four men to the top of the same hill and back. In another, a strongpoint of sandbags must be created from a pile of sand 500 meters away. In still one more they each carry an ammunition box to a remote outpost.

“We are not just testing their stamina; we are also looking at intelligence, problem-solving and how they interact with one another. They will take an IQ test as well,” said WO Pink.

Starting just after dawn on the first day, 230 volunteers and a few “voluntolds” take on these “tasks” of pain.

At the end of the first day of misery, around 200 remain. By the end of the second day, 176.

Each section is designed to break the will of the young men who wish to become ANA SF. Accompanying each group is an Afghan mentor to provide direct motivation and a Canadian Special Forces advisor to, well, advise. The Canadians keep the Afghan mentors and the would-be ANA SF — undergoing their purgatory of pain -– under a watchful eye to ensure fairness and safety.

On the third day, CSOR MCpl White stands by a small stream of grey-green water.

MCpl White is from New Brunswick; this is his fifth deployment to Afghanistan. He left behind a seven-day-old baby girl and a fiancee to come and do what he is doing now. [More]