Peter Kuper's Insectopolis: A Natural History

Peter Kuper, award-winning illustrator, comics artist and co-founder of World War 3 Illustrated, will launch his long awaited book Insectopolis: A Natural History, at the opening of an exhibition of the original work at Society of Illustrators this week. Peter is a long-time contributor to DART, going back to his first stay in Mexico, in 2006, when he fell in love with Monarch butterflies. But his passion for bugs goes way, way back to his childhood years, when he first took up the butterfly net when other kids his age were slugging it out on the local diamonds. So it was almost inevitable that Insectopolis would bring the many facets of his work as an artist, writer and educator together in a celebration of knowledge that also celebrates the place where much of the work was made: the main branch of the New York Public Library. Following is an interview conducted this week by email.

Peter Kuper: My clearest memory is in New Jersey in 1963, age 4, when the cicadas came out by the millions. Most people would run, screaming seeing them covering every tree. I however, was thrilled! Around that same time I was also reading P. D. Eastman’s, ‘Sam, and the firefly’ which was a favorite.

PR: Did this obsessive fascination bug your parents?

PK: My father had been an Eagle Scout so he was completely encouraging. He bought me a butterfly net and generally both my parents gave this pursuit the thumbs up—probably more than my next exploding passion, comic books.

PR: When did the topic first invade your work as an artist?

PK: The first notable point they crossed into my comics was my adaptation of Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, in 2002. But they made cameo appearances in my work leading up to that.

PR: Insectopolis is staged in the main branch of the NYPL— a place we don’t usually associate with bugs. Where did that idea originate?

PK: In 2019 I applied for a Cullman fellowship. My proposal was to do something like Guns, Germs and Steel, but about insects. The Cullman is given to 14 writers and artists each year. You are provided with an office and get to utilize the resources of the library to do your research. Being in that environment, it dawned upon me that the place itself would make a perfect backdrop for telling my story.

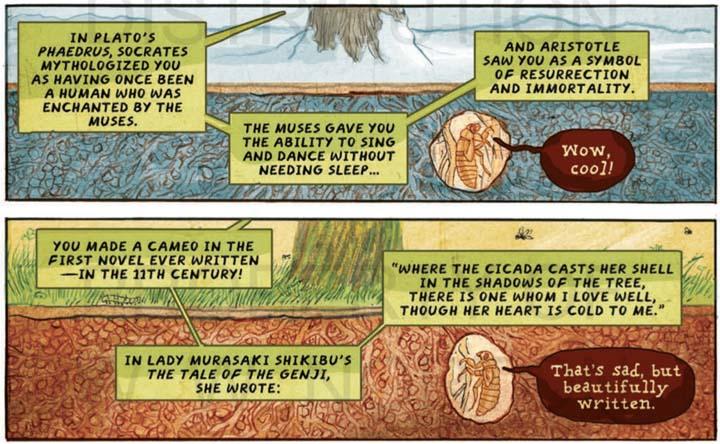

PR: As creatures of all description take over the great spaces in this Beaux Arts masterpiece, they tell their stories in the form of chapter-length autobiographical stories. What prompted you to have the regular population of scholars, tourists and other curious humans replaced by thousands of species of bugs?

PK: I received the Cullman during the fall of 2020. You may recall there was a pandemic going on at that time! The library was closed to the public, so only the people who received the fellowship, along with a few workers, were allowed into the building. Walking the empty halls, with virtually no other people around, made me much more aware of the architecture. It almost felt like being in a post-apocalyptic world, and that launched my approach.

PR: Were your drawings for Insectopolis inspired by any works in the NYPL collection?

PK: Absolutely. They have Vladimir Nabokov's butterfly drawings, Maria Sibylla Merian's original hand-colored lithographs she created of insect metamorphosis in the early 1700s, John Tenniel's original illustrations for Alice in Wonderland. They also have Charles Addams' archives and I looked at every one of those amazing original cartoons along with Arthur Rackham's original art created for a special edition he created just for the library of Shakespeare's Midsummer Night’s Dream—to name just a few of the mind-blowing items I was allowed to peruse.

PR: After you took your family to live in Oaxaca Mexico for two years, in 2006-2008, and following publication of Oaxaca Journal, you delved into a study of Monarchs that resulted in your next book, Ruins which, I understand, is just out in paperback. Please share with our readers how you began this process and why bringing this investigation—about the species, the migration, and ultimately, why/how climate change is the most significant issue of our times.

PK: I stumbled upon monarch caterpillars while hiking with my wife and daughter, and we gathered several and the milkweed plant that they subsist on and brought them back home and raised them in a terrarium. I was already interested and thought this would be a great project for my daughter, who was nine years old at the time. Visiting the site in Mexico, where all the monarchs migrate from Canada, (a 3,000-mile journey) planted the seed that became part of the book Ruins.

The whole migration is fascinating, and without having to do any political commentary, simply illustrating what monarchs have to pass through on their journey—urban areas over industry, strip mining, across borders, gave this an environmental and political subtext. As far as climate change goes, there's evidence of this growing problem everywhere. In Mexico there were droughts more recently, which led to fires. Of course, what recently happened in California, and what's happening all over the world is a constant barrage of evidence that we are in the midst of a major change in our planet.

In the course of researching for Insectopolis, I was reading books on past and current extinctions, and what the various impacts on insect has been. In fact, one of the reasons I started on that project was because of an article about the "insect apocalypse" that appeared in the New York Times magazine in 2018. I have been doing a weekly comic strip for the French magazine, Charlie Hebdo, that is all about the environment, so I have been looking into this subject for many years. What I found in my investigation is, we are actively poisoning our planet, which is to say poisoning ourselves and the natural world, and it doesn't require a degree in calculus to draw the line between our actions and this climate crisis.

PR: How have you used your sketchbooks to develop ideas— and highly detailed studies— for Insectopolis and the last few books? Do you find that the subject matter lends itself to a more direct style of drawing?

PK: I've tried to explore many different ways of storytelling, and drawing in general experimenting with a lot of different stylistic approaches. My sketchbook drawing has always been a resource and a place for me to experiment. I keep a little notebook in my back pocket at all times, so when I get an idea on the subway or in an elevator, I can write it down or sketch it up and not forget it. In Insectopolis, because each chapter could stand on its own I was able to change styles periodically in a fluid way that would not be jarring to the reader. I just find doing one single style gets monotonous but also I try to decide on what stylistic approach I use on any given project based on the tone I want to achieve. So adapting Kafka's work as I did in The Metamorphosis and more recently Kafkaesque, I did the art in black-and-white on scratchboard, which approximated wood cuts whereas, with other projects, I've used stencils and spray paint, or a combination of line drawing, and a more sketchbook approach with colored pencils, as I did, in my adaptation of Heart of Darkness.

PR: At first glance, Insectopolis appears to be an investigation into things of beauty— which it is. As a research nerd myself, however, I was stunned to learn, in the first dozen or so pages, why dinosaurs were able to grow to their colossal size— and that’s just one of the amazing bits of pure science you’ve folded into this beautiful book. With that in mind, please share with our readers: how did you come into contact with the scientists who shared resources with you?

PK: The first entomologist I came into contact with was Barrett Klein who I met at one of the New York City comic book conventions. I have often discovered that entomologists are also interested in comic books! He gave me pointers when I was working on Ruins, and then introduced me to a number of other entomologists, who gave me pointers for Insectopolis. I also just reached out to people whose books I read just by looking them up on the Internet. All of them were quite receptive to helping me make sure the information in my book was accurate.

PR: What are your hopes for drawing a general audience into the overarching subject of climate change?

PK: My first hope is to make people who find insects to be disgusting or frightening to reconsider and get a better understanding of their importance in making the world go round so their first reaction isn't just to stomp on them or spray them with insecticide. What's happening to insects is directly linked with climate change, so I believe if people are conscious of one, they will also find links to the other, and perhaps this will lead to more consciousness in general about protecting nature.

You can meet the artist this week in NYC and later at other stops along the book tour:

Thursday, May 22, 6-9pm: Exhibition opening and book launch party, signing {all of Peter's bug books], plus special guest Louis Sorkin and his live insect petting zoo. Society of Illustrators, 128 East 63rd Street, New York, NY Info Exhibition continues through September 20th.

Monday, June 2, 7pm: Picture + Panel conversation with Allison Conway. Boston Figurative Art Center, 285 Washington St, Somerville, MA Info

Tuesday, June 3, 7pm: A conversation with Harvard Entomologist, Crystal Maier. Harvard Bookstore, 1256 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA Info

Thursday, June 18, 5:30pm: Artist talk at the New South Bookstore. 105 S. Court Street, Montgomery, AL Info

Peter Kuper’s illustrations and comics have appeared in newspapers and magazines around the world. He is a regular contributor to The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Nation Charlie Hebdo and MAD where he has written and illustrated SPY vs. SPY since 1997.

He is the co-founder and co-editor of World War 3 Illustrated, a political graphics magazine that has given a forum to political artists for over four decades and has produced over two dozen books. He won a 2016 The Eisner Award, the 2024 Kennedy Journalism award and the 2025 Herblock Finalist Prize.

Peter has been teaching courses in graphic novels and cartooning at Harvard University since 2011.

If you would like to subscribe to DART: Design Arts Daily, please go here