Edel Rodriguez

The celebrated

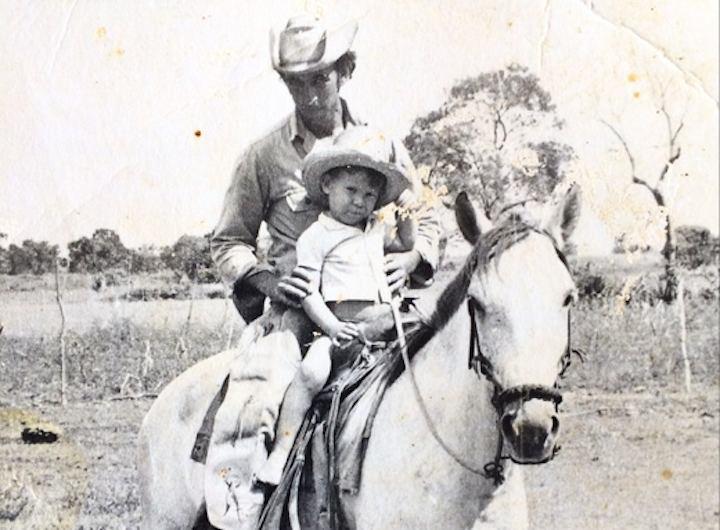

Cuban-born artist and illustrator Edel Rodriguez was a Marielito—one of 125,000 who migrated to the United States in 1980 during the mass exodus called the Mariel Boatlift. This

took place during a short-lived thaw in relations between the U.S. and Cuba. Edel’s family was on one of the first boats that landed in Key West. They lived in close quarters with

another family in Miami until his parents found work and their own place to live. Photo above: Caesareo Rodriguez

The celebrated

Cuban-born artist and illustrator Edel Rodriguez was a Marielito—one of 125,000 who migrated to the United States in 1980 during the mass exodus called the Mariel Boatlift. This

took place during a short-lived thaw in relations between the U.S. and Cuba. Edel’s family was on one of the first boats that landed in Key West. They lived in close quarters with

another family in Miami until his parents found work and their own place to live. Photo above: Caesareo Rodriguez

Just a few weeks before President Obama’s surprise announcement that the U.S. will restore full diplomatic relations with Cuba, Edel and his family were on their way to Havana to celebrate his solo exhibition at Casa de las Americas. The title of the show is Nature Boy—the name of the shrimping boat that carried him and his family to freedom 34 years ago.

In the process of preparing for the show and the trip, Edel mined his family archive of photographs, which began appearing last summer on his Facebook page. Following are some extracts of his commentary on those images, and new photos from his recent trip to Cuba. You can read a recent interview in Print magazine here. You can view his recent photos from Cuba on Instagram/Roads & Kingdoms here. Visit his website here. His work is included in Illustrators 57, opening this Friday at the Society of Illustrators.

Edel left front,

with his extended family in El Gabriel, La Habana. Photo: Caesareo Rodriguez

Edel left front,

with his extended family in El Gabriel, La Habana. Photo: Caesareo Rodriguez

My father was the town photographer in Cuba in the 1970s. He built a darkroom in the back of the house, and would hang negatives from the ceiling; I remember walking through all of it to take a bath. I spent a lot of time with him developing pictures. Seeing the images appear out of thin air was kind of magical--thats probably one of the reasons why I remained interested in photography.

He built a small history of Cuba at that time, even though that may not have been his intention. He shot with small Russian cameras at first and later with large

format Mamiya cameras that family members brought him from the U.S. His success in town brought attention. New friends appeared, curious about his business. One of them made notes, a list of

all the equipment he owned, along with everything else in our home. When we were ready to leave the country, soldiers came with the list, the government confiscated everything. The

house, darkroom, cameras. It all now belonged to the revolution.

The idea [for the exhibition] developed over several years, first via online exile designers groups and later personal visits with some of the designers and curators on the island. When I left in 1980, we were considered traitors, called names, and some people were beaten, amongst many other injustices. For someone like me to come back to Cuba, after having had success in America, can be a very complicated thing. I was told that it was not easy, but the people I was working with pushed and pushed to make it happen. This was like putting on any other art show, but with international political intrigue thrown into the mix.

I titled my show “Nature Boy”, after the name of the boat I left the island on in 1980. I didn’t know how this would be received, but the young people I was working with embraced the poetry of it all and promoted the concept to the media. Here I am signing silkscreened promotional posters printed at one of the factories on the island. Photo above by my show’s curator, Cristina Figueroa

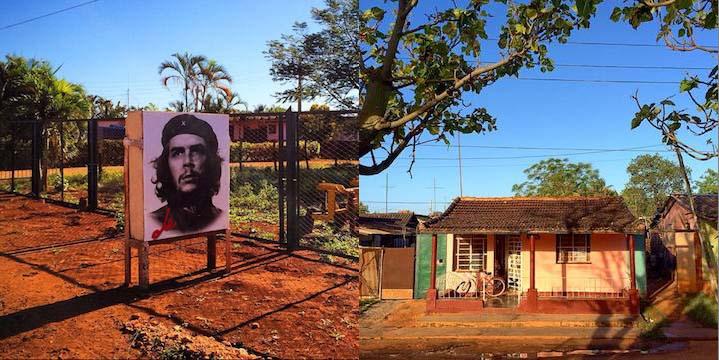

Portraits of Che Guevara are everywhere [left]. Much more than those of Fidel or Raul Castro. He's promoted as a martyr for the revolution, which helps the regime and those still in power. This poster is in front of a farmer's collective near my hometown.

One day I was speaking with a computer technician about the lack of internet access on the island. They have one fiber optic cable coming in through the sea from Venezuela. I wondered, is the lack of access due to bandwidth? He looked at me incredulously and said "It's about control, man, control." We looked up and a giant portrait of Che was looking down on us, like Big Brother. Photo byEdel Rodriguez.

This is the house I grew up in [above, right]. I am staying at my grandparents’ house next door. The family has lived on this small plot of land for about 100 years. When my dad was growing up, this was an empty yard. He married my mother and was given the yard as a gift by the family, and together they put up this small house on it. It was the start of the Revolution, there was little money and supplies were very scarce. It took my parents about 8 years to build this house, and then I was born.

Our house, and all of its contents, were confiscated by the Communist government when we left the country in 1980. We could not hand it down to our family. The Communist government gifted it to someone in the Party. The family still lives there to this day, they are nice, always lets me walk through and take photographs of the rooms I used to play in.

The issue of property rights will be a big one if Cuba is ever to be an open country. Many people assume that the properties that were confiscated by the Communist Party were all owned by big American corporations, but that’s not the case. Many properties were owned by poor families like mine. Families that worked very hard to build small houses and farms. Houses are not just property. Houses are history, family, and memories. And many people feel all of that was taken from them by the Communist Party when their homes were seized. Photo by Edel Rodriguez