DIARY: Isamu Noguchi, A Sculptor's World

Anniversaries are probably celebrated more by publishers than by lovers—so as a book-lover I’m taking this opportunity to celebrate a book that came into my hands almost ten years ago: Isamu Noguchi: A Sculptor’s World (Steidl 2018).This is a great time to take a deep dive into this exceptional publication, in light of the exhibition, Noguchi’s New York, which just opened at the Noguchi Garden and Museum,. The book went out of print around 2022, but a new edition will drop in June.

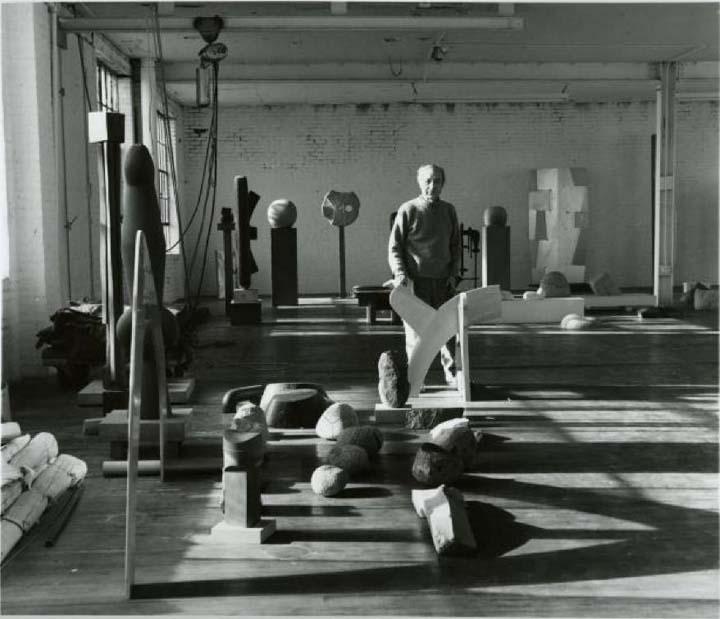

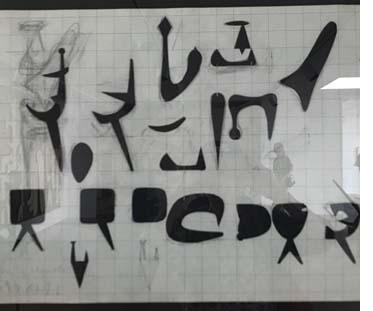

I came across the book (which is in fact an autobiography) when The Metropolitan Museum of Art presented Epic Abstraction, which occupied the entire top floor of the museum’s contemporary art wing, and opened with the Noguchi pink marble Kouros (photo above by Marco Palli). The piece is one of fifteen or so interlocking sculptures made by the artist between 1945 and 1948, using his extraordinary kit of abstract parts (see photo below, and diagram below left) to create human-scale free-standing pieces that are held together by gravity. About this work, Noguchi (1904-1988) wrote, "You have to consider the weight of the material, the forces that conspire to hold up the figure — engineering problems, essentially. Everything I do has an element of engineering in it — particularly since I dislike gluing parts together or taking advantage of something that is not inherent in the material . . . there are no adhesives of any kind — only the stones holding themselves together."

Between the book and this single piece of sculpture, I was swept into the world of this extraordinary sculptor, who during his studies at the Leonardo da Vinci Art School on New York City’s Lower East Side was told that he possessed qualities that would inform “the next Michelangelo”. With that idea in mind, and funded by a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship in 1927, at age 27, he went to Paris to become Constantin Brancusi’s first (and only) assistant. After six months working with the master, Noguchi developed an innate feeling for the restless, irregular forms he had begun shaping around the void—abstract figurations that were highly expressive of an age of anxiety that characterized the period between the wars. He later wrote, “It became self-evident to me that in the so-called abstraction lay the expression of the age and that I was especially fitted to be one of its prophets.”

At the end of the decade Noguchi returned to Japan, where he began a life-long conversation with earth, stone, water that resulted in the many public gardens he created, and where he resided for part of each subsequent year. He wrote, ''Stone is the fundament of the earth, of the universe,'' he said. ''It is not old or new but a primordial element. Stone is the primary medium, and nature is where it is, and nature is where we have to go to experience life.'' Noguchi defined direct carving as ''a process of listening….’When I'm with the stone,'' he said, ''there is not one second when I'm not working. I'm so involved in doing the right thing.''

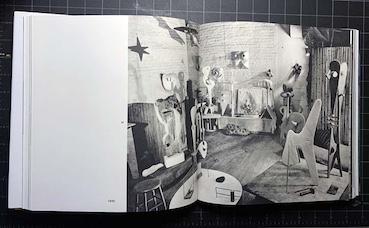

The book devotes a number of pages to the drawings and models for the series that claims Kouros as a member. The black-and-white photos in this section are by the artist as well as by Rudy Burckhardt, George Platt Lynes, and Andre Kertez. And this is one of the reasons that the book is such a treasure. Among the pages are shots by some of the greatest of the great mid-century photographers who looked in on Noguchi's world, including Evelyn Hofer, Alexandre Georges, Philippe Halsman, Barbara Morgan (above), Arnold Newmann, Hans Naumuth, W. Eugene Smith, Ezra Stoller and Martha Swope.

Isamu Noguchi: A Sculptor’s World was originally published in 1968 by Harper & Row, in conjunction with the Whitney Museum of American Art’s retrospective exhibition. Steidl’s first and second editions were 2004 and 2015, with a third edition in 2018 to commemorate the artist’s death.

The book went out of print in 2020; Steidl will release the long-awaited new edition on June 2; you can preorder here. More about Noguchi, and sculpture in general in DART. sculpture2019.19