Developing an effective illustration curriculum for the 21st century

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a series of presentations made at ICON8 in Portland. The ICON8 Educator's Symposium celebrated new and innovative methodologies for teaching illustration in the 21st Century.

This two-part event at the Pacific Northwest College of Art as part of the ICON8 pre-conferneceworkshops, July 9-10, 2014, featured a presentation of papers by a global selection of noted educators, and a round-table discussion on traditional and online learning.

Produced by ICON8 education board chair Rick Lovell, Illustration Program Coordinator, Savannah College of Art and Design with ICON8 vice president Robert Brinkerhoff, Department Head, Illustration, Rhode Island School of Design. View a selection of the presentation papers here.

This paper discusses how digital access to previously difficult-to-access stages of the creative process can help students of illustration in the understanding and development of research, ideas, thinking, technical skills and, most importantly, confidence. The vastly expanded intake of university students in the UK in recent years has presented new problems for educators as well as for students themselves. In particular, first-generation students new to the university and/or the system of higher education are often quietly or silently embarrassed by their lack of understanding of what is required in the pursuit of creative thinking and subsequent development of ideas. They can be susceptible to doubts about their abilities. We need to transform their thinking by encouraging them to let go “…of earlier, comfortable positions and (fear of) encountering less familiar and sometimes disconcerting new territory.” (Meyer, Land et al 2004: page 54).

Jackson states that: “Creativity lies at the heart of a student’s own identity” (2006: page 16), suggesting that we must “encourage risk taking in safe environments and help students to engage with messy/complex and unpredictable situations where there are no right and wrong answers” (2006: page 12). As a university education is increasingly about the holistic development of the student it is crucial that we get this right. Dunn states that: “By stimulating the senses, especially the visual sense, learning can be enhanced.” (2000: pp 20-30). Whereas, Laird quotes research that found that the vast majority of knowledge held by adults (75%) is learned through seeing (1985). The first few weeks of a student’s course are essential to establishing their wellbeing and confidence; this can be expedited in classroom/studio sessions that put them at ease and reassure them by giving them a clear picture of pathways to creative thinking. New students need to feel comfortable with their new environment before they can begin to learn. It is of equal importance for students further on in their BA degree course or for MA students to feel confident about their approach to their work. Darling-Hammond, Orcutt et al discuss the need to create and foster “a meaningful curriculum” (2003: p 94) in order to achieve this.

In this paper we describe one conduit for this, an online research resource developed by Seven Stories: the National Centre for Children’s Books in Newcastle on Tyne in the UK in which all aspects of their archive collection, which includes every stage of the development process and final artwork of post-war to modern British children’s book illustrators, is made digitally available to students along with related correspondence between authors, publishers and illustrators.

It is worth noting that In my own (Alison Barratt) experience as a freelance illustrator and designer the background work to illustration projects that provides such insight into the creative process was not so long ago not considered of enough importance to preserve.

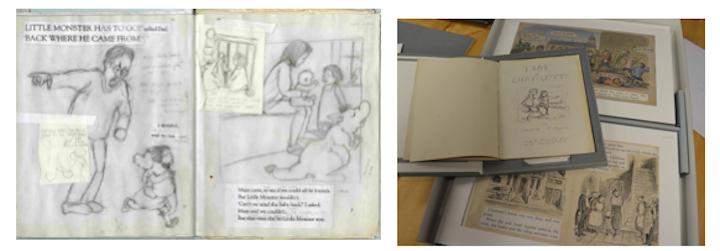

Above, dummy page, Helen Cooper; right, dummy pages, Edward Ardizzone.

Above, dummy page, Helen Cooper; right, dummy pages, Edward Ardizzone.

Background

Methods and possibilities for illustration have been changing at an ever-increasing speed. The teaching of illustration is reflecting this: it has adapted to and embraced the digital and the ever-expanding platforms for its use and will continue to do so. Nevertheless traditional methods of experimental development remain core to the success of the final illustration. “As much as computers have invaded the field, I think traditional illustration (brush, paint, pen, etc) will still win out, visually, over digital. However, I do believe deadlines will continue to shorten, and the skill level of the Illustrator will have to raise to keep pace with digital manipulation from computers.” (Heron, WOSU Public Media. 2012. mycooljob.org. [ONLINE] Available at: http://mycooljob.org/wise/illustrator.php. [Accessed 16 November 14]. Indeed traditional skills are more important than ever to understanding and practice in order to give substance and conviction to what could slide into over-dependence on the easy impressiveness of instant digital results. “Despite the speed at which hardware and software developments move, and despite the speed of change across apps, social media and online environments, there continues to be a genuine need for more in-depth understanding and knowledge, and for a more deeply developed practical skill-set.” (Zeegan, 2013: p.219). With the widening student population it has become increasingly important to educate students as early as possible in their university education (and arguably at secondary school) to be aware of the depth of communication gained by using traditional methods of analysis, thinking, idea development, exploration, thereby achieving greater professional satisfaction for both illustrator and client.

The question explored by our project was what would result from exposing the ‘warts and all’ of the visual creative process to students, from showing them that the process of creating a successful illustration is as experimental a process for experienced illustrators as it is for the first-year student. Could this help to unblock that fear of being ‘wrong’ or ‘useless’ that so many students suffer from? Could it encourage students to become more confident about exploring their own, unique potential openly and freely, releasing unseen potential and stimulating new ways of visual thinking? We have in mind here Colbeck , Cabrera and Teranzini’s argument that: “Students' classroom experiences are critical to their persistence.” (2001: p174)

Development of the research idea

Seven Stories has always made its collection available to interested parties via exhibitions, events and in-person research visits but not digitally other than via examples on its visitor centre website (www.sevenstories.org.uk). By bringing their collection into the digital classroom (and thereby creating global access for all), we wanted to find out if students would learn more effectively, teachers teach more effectively and whether the resulting illustrations would be richer and more professional. What would result from the creative collision between ‘old’ material and new digital ways of working and learning?

Following the success of previous collaborative projects, Carey Fluker Hunt (Creative Projects Manager at Seven Stories) suggested that we might explore this question by collaborating on a pre-digital pilot project focused on opening up the pedagogic possibilities of the physical archive material. This fitted my on-going concerns about how to help students understand the importance of research as a basis for their visual thinking. Barron and Darling-Hammond (2008) state that ““When students have no prior experience with inquiry learning, they can have difficulty generating meaningful driving questions and logical arguments and may lack background knowledge to make sense of the inquiry. Students can neglect to use informational resources unless explicitly prompted. They can find it hard to work together, manage their time, and sustain motivation in the face of setbacks or confusion.” As they suggest, “Students engaged in inquiry-based learning develop content knowledge and learn increasingly important twenty-first century skills, such as the ability to work in teams, solve complex problems, and to apply knowledge gained through one lesson or task to other circumstances.” Barron and Darling-Hammond (2008)

We needed to show students methods of inquiry step-by-step so that they could understand that the working process of research is not something to be afraid of but is very enjoyable; that it is about curiosity, about finding out, it is about helping them to be self-determined. Field and Hoffman (1994: p164) define self-determination as "the ability to identify and achieve goals based on a foundation of knowing and valuing oneself". What we needed at the university was such a project as Carey had invited us to participate in: a professional ‘real-world’ context or model that challenged and inspired, fuelling students’ development as Illustrators by opening up their understanding of the creative practice of others, of the process of making a picture-book, including liaising with publishers as well as professional demands and expectations, thus creating an environment to motivate them to take a genuinely creative and adventurous route towards their goals. “Fundamental to expressing and practicing self-determination in real settings is encouragement for appropriate risk taking” (Field & Hoffman, 1994b). As Barron and Darling-Hammond (2008 http://www.edutopia.org/inquiry-project-learning-research) state: “A growing body of research demonstrates that students learn more deeply if they have engaged in activities that require applying classroom-gathered knowledge to real-world problems.”

What we wanted to find out was what kind of materials students would be interested in. Over the period of a semester (Jan – May 2012) the 23 students in the second year of the BA Illustration and Design course at the University of Sunderland were taken to the archive collection at Seven Stories and shown a wide variety of materials.

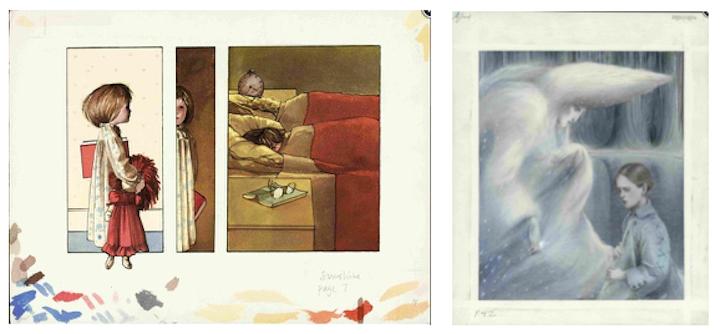

Above, finished artwork Jan Ormerod; right, finished artwork Angela

Barrett.

Above, finished artwork Jan Ormerod; right, finished artwork Angela

Barrett.

More material was brought to the university for a series of workshops in which students explored the contents of the archival boxes from sketchbooks to final artwork and correspondence from those involved in the publication process. A collection of picture books designed to widen students’ awareness of the range of books that are published for children was included. The books either addressed real-world issues or showcased creative approaches to book design or page layout. The idea was to assess the impact on students in seeing how original materials benefited and challenged the students and what parts of the process were particularly beneficial. According to Bandura, showing examples is one of the most effective instructional strategies: “Cognitive representations of experiences in knowledge structures provide the substance for thinking." (1989: p9). He also states: “Students' beliefs in their efficacy to regulate their own learning and to master academic activities determine their aspirations, level of motivation, and academic accomplishments.” (Bandura, 2010:p1)

The examples of development work were taken from the publication period 1950 to the present and included illustrators such as William Stobbs (Chanticleer), Bob Graham (Jethro Byrde, Fairy Child), Angela Barrett (The Snow Queen), Sarah Garland (Billy and Belle), Pat Hutchins (One Hunter) and Gillian McClure (Tog the Ribber). The project’s illustration brief was introduced at the start of these workshops: it was to illustrate part of an original manuscript for the story ‘My Dad’s a Birdman’, written by David Almond and published by Walker Children’s Books with illustrations by Polly Dunbar, which are also held by the Seven Stories Collection.

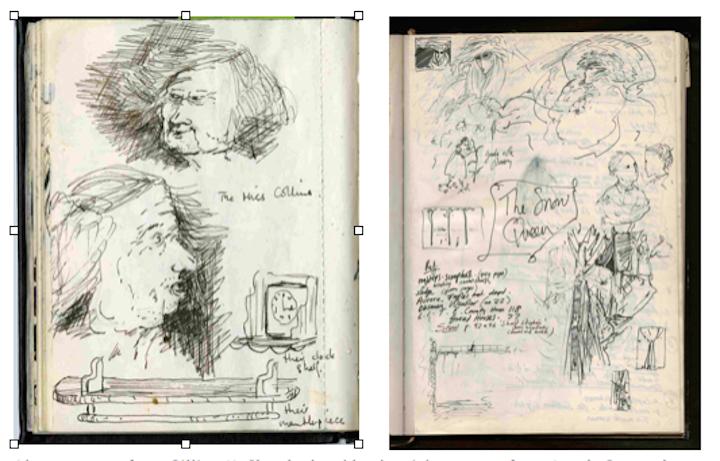

Above, a page from Gillian McClure’s sketchbook , right, a page from Angela Barrett’s

sketchbook.

Above, a page from Gillian McClure’s sketchbook , right, a page from Angela Barrett’s

sketchbook.

Applying the results of this pre-digital pilot project to ‘Picturebook in Progress’.

The results of the pre-digital project were powerful. They confirmed the importance of certain aspects of the creative process, such as sketchbooks, storyboards, dummy books, correspondence illuminating the editorial relationship and their creative impact on students; in particular, the evidence of ‘mistakes and dead-ends’. Students saw that expecting to create a ‘perfect’ image first off is unrealistic and perhaps not conducive to the learning process. They saw that professional illustrators build through exploration. It reassured them. The question now was whether a similar project based on these findings would work for other institutions, other students, with differing age ranges. The project was expanded - thanks to funding from the Arts Council England to include students from the MA Illustration course at Edinburgh University, MA Children’s book illustration students at Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, and sixth form students studying art (16-18 years old) at St Cuthbert’s Boys’ School in Newcastle on Tyne. This expanded project was called ‘Picturebook in Progress’.

In their impact and outcomes both projects exceeded initial expectations. Click here to listen to Carey Fluker Hunt talking about this first stage. Below are examples of the responses from students involved in both pre-digital projects:

Sketchbooks: “It showed me mistakes can actually be better for your work than trying to get it right the first time around”. BA student University of Sunderland

Storyboards: “Seeing the storyboards and final artwork shows me that I need not focus on getting a final piece at the first try. It’s a process of drawing, redrawing, working out; that there is a lot of behind-the-scenes work before a final piece.” MA Anglia Ruskin student

Dummy books: “What helped me the most was the dummy books, which really helped me to (know how to) plan out my work.” BA student University of Sunderland

Character development: “I thought that looking at the artists’ original work helped me develop my character to make it better and more detailed”. St Cuthbert’s student

Final artwork: “(What surprised me was) the state of many original drawings such as the lots of correction paints on Judith Kerr’s originals of ‘The Tiger Who came to Tea’.” MA student Edinburgh University

Techniques: “It was useful to see a variety of media experimented with in a sketchbook, then the finished result to see how the chosen media was applied and how it looked when printed.” BA student University of Sunderland

Publication: “The most interesting thing to me was the correspondence between authors publishers and writers. It showed us a world that we as illustrators still do not know and lets us understand how things are made”. MA student Anglia Ruskin

Summing up: “My expectations were beyond fulfilled, (to see) not just finished products but also the processes behind those products… I found incredibly helpful. I’m very happy about that”. MA student Edinburgh University

Example of tutors’ responses to seeing the collection:“(Seeing the collection has) tipped them over from being sixth form (age 17) artists to really thinking that they can make a go of it on their own. It has given them loads of confidence.” Tutor St Cuthbert’s Boys’ School

“What I do think stood out best was showing (the students) zoo those sketchhbooks, seeing all the observational drawing illustrators were doing and the feeding (of) themselves creatively outside of working on projects, that’s really useful for students and I think stood out for them.” Tutor Edinburgh University

And listen to what Pam Smy, MA tutor at Anglia Ruskin University has to say.

Looking at the feedback from students and staff it was clear that the collection material really was a revelation. A big plus was that students were learning that ‘mistakes’ are simply other ideas and might be useful in the future and not to be dismissed or ashamed of. “Mistakes are the most important things that happen in any classroom, because they tell you where to focus deliberate practice.” (Maats and O’Brien, 2014: http://www.edutopia.org/blog/teaching-students-to-embrace-mistakes-hunter-maats-katie-obrien)

Students were learning what research meant and there was a resulting richness, depth and excitement in their work. They relaxed: “Research can be creative and empowering, and [to] give them ownership over their own work.” (O'Loughlin-Brooks, 2004:p26); they were beginning to understand the relationship with publishers and writers and that illustrators do not work in isolation but as part of a team.

Building the digital resource

Seven Stories wanted to make its Collection holdings available to all illustrators and would-be illustrators not just those who could visit the archive for themselves, and to create a resource such that they could browse at their own pace, follow their own research interests in their own time wherever they happened to live. It was possible to build a digital resource - but should such a resource aim to replicate the experience seeing the original materials “face-to-face”, or should it offer a different kind of experience? Seven Stories commissioned the making of a prototype based on the need and interest expressed by students taking part in the pilot project.

Images from the collection were digitised and interviews with illustrators were added along with links to other websites; suggestions for reading and text commentary. In short, an attempt was made to bring everything together in one place that would provide an interesting journey through the process of making a successful children’s book thereby creating a curated experience for the user rather than supplying simply an online catalogue of the Collection’s holdings. Although the digital resource cannot replace the excitement of handling the original materials, it does allow for a close and satisfying examination of texture and detail and there appear to be many additional benefits gained by digital access. It enables students’ cognitive skills: they learn to explore for themselves in an environment in which they are comfortable; they take more responsibility for their own learning. “Easy electronic access to well-organized instruction in virtually any subject creates extensive learning opportunities that transcend time and place.” (Bandura 1997:p212-258).

Here, Carey Fluker Hunt speaks about the building of the prototype.

The Digital Learning Resource (DLR)

The DLR is a work in progress and as yet only some of the material in the collection has been uploaded. However, even at this early stage the resource features more than forty illustrators, including archival material by Edward Ardizzone, Anthony Browne and John Burningham alongside video interviews with John Lawrence, Shirley Hughes and Levi Pinfold, amongst others. Manuscripts are also represented, with material showcasing the collaboration between successful author-illustrator partnerships such as Martin Waddell and Patrick Benson, and Terry Jones and Michael Foreman, as well as correspondence between illustrators and their publishers. The editorial perspective is a particular feature of the resource, as one of its aims is to clarify the illustrator’s role in the publication process and provide a window into the ‘real world’. To date, staff at Walker Children’s Books have contributed via video commentary and more interviews will follow.

The home page invites the viewer to choose between two chapters - ‘From First Ideas to Finished Book’ and ‘My Dad’s a Birdman’. Clicking on an icon leads to a choice of ‘chapters’: in the case of the first title, these deal with aspects of the creative process of making a picture book and include sketchbooks, character development, storyboards, dummy books and finished artwork. The ‘First Ideas’ section, for example, features digitised pages taken from the initial idea generation and exploratory work of a number of illustrators including Angela Barrett, Sarah Garland and Gillian McClure. Video interviews with other illustrators are included, along with a voiceover commentary, links to illustrators’ websites and related books for further reading. Other chapters have a similar structure, offering a curated experience, and users can browse freely or use the search function to locate required material. A benefit of the resource is that it enables the creation of portfolios in which students can collect everything of interest for personal use.

As we have already noted, in the past the development work of professional illustrators was not regarded as an important pedagogic tool for students and rarely available other than through a student knowing an illustrator personally. Archive material per se was rarely available to anyone other than scholars or administrators, yet it “…provides fruitful opportunities for engaging students… and provides a link to the present.” (Kafai and Gilliland-Swetland, 2000: p366). Viewing and exploring through digital access makes research an activity that students can engage in with relative ease and relate to with a sense of recognition of their own way of working.

Web-based instruction has revolutionized how students work, think, and access information: “These tools engage students in focused problem solving, allowing them to think through what they want to accomplish, quickly test and retest solution strategies, and immediately display the results.” (Peck & Dorricott, 1994: p 11-14). It nurtures their confidence and motivation. (Daugherty and Funke, 1998: p 21-39). One unexpected and valuable teaching tool is that a well-designed learning support, as in the structure of the digital resource provides clear and stable guidance for the student to learn about the nature and development of creative visual exploration, a process that is a revelation to many contemporary illustration students. The necessity of a strong pedagogic structure is discussed by Hsun-Fang Chang and Gwo-Jen Hwang (2010: p 1023-1031)

To explore this resource further and to contribute to the development of the website please contact Carey Fluker Hunt at carey@sevenstories.org.uk. If you wish, you can go directly to the website. Part of each title is freely accessible although a subscription is needed for full access: http://research.sevenstories.org.uk/.

The subscription payable depends on the duration of access required. Multi-user subscriptions are available to educational establishments. Seven Stories, itself, is an educational charity and funds raised via subscriptions will be used to maintain and develop the resource.

Student Response to using the Digital Learning Resource (DLR)

At the time of giving this paper at ICON8 the prototype website had only been online a few weeks and written feedback was minimal, though a number of students and tutors had been interviewed (see figures below). Further research results will be written up in due course.

From the start of the pilot project we began to learn more about how students learn and this insight will inform and influence our teaching methods in future projects and hopefully result in increased student confidence at an earlier stage in their education. “Understanding the basis of student performance can help us identify appropriate teaching practices or approaches.” (Cerbin, 2009: essay).

Results so far suggests that students do indeed respond positively to discovering the ‘warts and all’ of illustrators’ development work. They are beginning to realise that their own instinctive ways of working are not only ok but to be enjoyed and nurtured; they are beginning to allow themselves to be reassured that their ideas and/or sketches are not ‘mistakes’, ‘worthless’ or ‘embarrassing’ but valuable tools with which to explore an idea. They can see that re-working and pushing through with an idea is necessary for progress; that to question and doubt is part of the creative process; that it takes time and effort to achieve what they are aiming for.

Additionally, students exploring the DLR can enjoy the revelations of video interviews; hearing from published illustrators themselves about the creative process; learning from the commentators’ observations as well as being able to set up and gather information in their own virtual research portfolio to peruse in their own time. Further to that, the Digital Learning resource helps to introduce them to, and reassure them about, the ‘real’ world that they need to learn to negotiate once they have graduated. The students who have been interviewed and those with whom I have worked seem to be increasingly relaxed about exploring the unknown and are pleasantly surprised about what they can achieve when they do.

Below are synopses of the videos of students shown at ICON8. If you wish to see and listen to the videos for yourself please click on the following links: MA student University of Sunderland ; BA student University of Sunderland; BA Illustration level 2 group.

MA Illustration student at the University of Sunderland:

Seeing sketchbooks of ‘real’ illustrators on the prototype surprised this student by showing that sketchbooks are places to experiment, doodle and work things out; they do not have to be ‘pristine’, it doesn’t matter (what they look like). It reassured her that ’famous’ illustrators are normal people who have had ‘bumps and struggles along the way’ and that it is a case of perserverence. While researching the website for inspiration about character development this student understood that exaggerating features gave her a way forward to visualising her intentions. She appreciated the diverse selection of work that is offered on one website.

Second year BA Illustration student at the University of Sunderland:

This student liked the fact that the collection breaks down the process of making a picturebook so that the process can be understood from start to finish through the different sections. Being able to explore the area that most worries him (such as starting or finishing a project) and seeing that professional illustrators have difficulties too, is very reassuring. Being able to explore such a resource at any time of the day or night is a great bonus. He is also aware that this idea development process is applicable to any other visual job he might be working on.

Round the table discussion between BA Illustration students at the University of Sunderland:

Student 1 who is currently looking at story and character development finds it exceptionally helpful in that it has taught her to make numerous sketches of different poses, characteristics, expressions in order to ‘get to know’ her character as well as making notes next to visual studies. Prior to exploring the Digital Learning Resource she had not realised this. Student 2 thinks that students’ creativity can be helped because it allows them to see other artists’ work and think that they too can work like that – it gives them confidence. She had found that there is nothing else like this anywhere online, where everything is in one place. Student 1 finds that it gives insight as to where to begin with a project just as the actual Collection in Newcastle does.

Final year BA Illustration student at the University of Sunderland:

Exploring the prototype has encouraged this student to trust her instincts. She finds the video interviews with illustrators inspirational. Again she finds it reassuring to find that professional illustrators ‘get stuck’ or frustrated just as she does and that they go through the same process as she does. Everything that they (as students) have been taught is what they do too. It has given her confidence in her work and motivation to make it to the top. As well as for herself she sees it being really helpful to first year students when they are fresh and open to new teaching.

Tutor responses to the prototype have been very encouraging:

“It’s virtually impossible to show background material, development and research from any other source.” MA tutor Edinburgh University.

“We don’t want to be without it now.” Tutor St Cuthbert’s Boys’ School

“The students haven’t had access to anything like this before. It will influence the way they work without a doubt.” MA tutor Anglia Ruskin University.

“It’s a valuable support tool for tutors too; it helps to teach students exactly what creative research means.” BA and MA tutor University of Sunderland.

Carey Fluker Hunt sums up by saying that all who have responded so far have done so very positively, whether they have been students, illustrators or staff who have been involved in and contributed to the project. It has become clear that that there is nothing like this available as yet; it is unique in the way that it explores the full range of the creative process. There will be subscriptions at certain levels depending on the depth of information required, but students will be able to explore a large amount of materials free of charge. The opening up of the archive collection is having a far bigger impact than expected on student understanding of research and creative thinking as well as being support for tutors. The full launch of the resource is currently scheduled for September 2015, though project participants and other interested parties have already been invited to access the materials. Should you wish to use the DLR then please email Carey Fluker Hunt at carey@sevenstories.org.uk or visit http://research.sevenstories.org.uk

The Future of the Digital Learning Resource

The Seven Stories Digital Learning Resource is a model for future learning possibilities, harnessing all stages of the visual creative project and making it accessible to all through digital access whilst allowing the student time to gather relevant information and absorb it at their own pace. Feedback tells us that the archival materials in themselves are a welcome and pleasant surprise and have the capacity to affect the illustration student in a clear and inspirational way, and the DLR has the capacity to expand upon this as a way to preserve and to share, for example, intimate illustration history, thinking, techniques and processes. Through correspondence the archive shows students that working as an illustrator is a collaborative process, and the DLR, too, could in time become collaborative: a focus, maybe, for an interwoven global illustration community engaging in discussion to enhance the strength of understanding of the power of illustration. Live online events could be joined by anyone no matter where they were in the world. The DLR could even provide links for showing work and discussing it with publishers and writers. And with growing reach, more illustrators may be encouraged to donate their work to the Seven Stories Collection, thus preserving it for the future as well as increasing the DLR’s impact and pedagogic value.

Significantly, the DLR provides a doorway to a new approach to illustration where students can be more confident of their work and feel freer to explore their own paths, reassured that their tentative thoughts, ideas and ways of working are similar to that of many successful illustrators before them. The Digital Learning Resource inspires creative excellence; it makes clear the nature of visual research is as well as the rewards of that research.

To end this paper I would like to quote the feedback from a level 1 Illustration student that seems to exemplify the present and future rewards of this resource: “I felt at ease knowing that I don’t have to be perfect in my sketchbook… that’s made me feel happy.” The Digital Learning Resource offers creative freedom.

Data on which this research is based.

2011 -12: 25 BA Illustration students from the University of Sunderland took part in the pilot project.

2013 -14: to date, 25 BA and MA Illustration students from the University of Sunderland; 39 BA and MA Illustration students from Edinburgh University; 50 MA Illustration students from Anglia Ruskin University; 24 students from St. Cuthberts’ Boys’ School and 7 MA and PhD students from Homerton College, Cambridge have taken part in the Picturebook in Progress project.

The Picturebook in Progress project was supported by Arts Council England through its Strategic Museum Development programme.

Seven Stories is the UK’s National Centre for Children’s Books. The museum holds an extraordinary collection of manuscripts, artwork, related archival materials and books by leading British writers and illustrators, from the 1930s to the present day. Highlights of the illustration holdings include substantial holdings of original work by Edward Ardizzone, Harold Jones, Judith Kerr and many others. To find out more, go to http://www.sevenstories.org.uk/collection.

Author:Alison Barratt, Senior Lecturer and Programme Leader for Illustration and Design. The University of Sunderland, Design Centre, City Campus, St Michael’s Way, Sunderland SR13SD, United Kingdom. Email: alison.barratt@sunderland.ac.uk