The Portland Papers, Vol. 1

Smart Image, Social Impact: Teaching Illustration and Design Responsibility

for Social Change and Innovation

Esther Pearl Watson, Associate

Adjunct Faculty, Art Center College of Design

Martha Rich, Adjunct Assistant Professor, Fashion Institute of Technology

Editor’s Note: This article is first in a

series of presentations made at ICON8 in Portland. The ICON8 Educator's Symposium celebrates new and innovative methodologies for teaching illustration in the 21st Century. This two-part event at

the Pacific Northwest College of Art as part of the ICON8 pre-conferneceworkshops, July 9-10, features a presentation of papers by a global selection of noted educators,

and a round-table discussion on traditional and online learning. Produced by ICON8 education board chair Rick Lovell, Illustration Program Coordinator, Savannah College of Art and Design with

ICON8 vice president Robert Brinkerhoff, Department Head, Illustration, Rhode Island School of Design.

Teaching Illustration and Design Responsibility for Social Change and

Innovation.

This article discusses a newly developed class (Smart Image/Social Impact) tailored to the illustrator with a focus on the development of critical thinking skills, experimentations with visual techniques and the understanding of ethical issues in design. The goal of this class is to prepare the illustration student to enter the expanding field of design for social innovation and to broaden their problem-solving skills beyond the visual.

The Class

Smart Image/Social Impact was created as an introductory class for Illustrators

wishing to enroll in the Designmatters concentration at Art Center College of Design. With the mission to utilize art and design

education as a catalyst for change, Designmatters offers students at Art Center a range of courses, and a certificate option. Through Designmatters, students, faculty and alumni from

across disciplines are engaged in an ongoing exploration of the role of art and design in effecting large-scale sustainable change through innovative partnerships locally and around the world.

Students from any department may enroll inDesignmatters classes, many of which are team taught and interdisciplinary. A key element of the Designmatters curriculum are, real

world, project-based courses"where Art and Design meets social change" (Designmatters, 2014).

The Instructors

Since 2005, with the support of Department Chair, Ann Field, the Illustration department has hosted Designmetters classes. We taught three of these classes together and found that we make a strong collaborative team. We also discovered that there was a positive response from students who worked on the real world projects. This experience gave us the opportunity to impress on them that the skill and portfolio building so central to their education can be used to pursue issues about which they are passionate, and to facilitate positive social and humanitarian change.

The Students

Eleven Illustration students with varied backgrounds signed up for the inaugural class. They filled out a course evaluation when the class was completed and their feedback, comments and suggestions were used in this paper.

The Projects

Art Center runs on a trimester system. Each term lasts 14 weeks with the class meeting once a week for 5 hours. The coursework was based on four

projects each with a different focus: Human Rights, Urban Responsibility, Cultural Sensitivity, and Images for Change. Each project lasted 3 to 4 weeks.

THE HUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT

Students were asked to create a 3-dimensional interpretation of a single article from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Basic Rights

We asked the students to make a list on the board of basic human rights. The students quickly discovered that what to them seem obvious human rights issues become more complex in different contexts. Many in the class were not aware of the assumptions they make based on, for instance: gender, class, culture, or race. This need for critical self-reflection became a recurring theme throughout the term.

Finding Agency within Images

The class was asked to clip images from the New York Times to discuss. One photo of crying children elicited a sad feeling from the class, but also a lack of agency. Students brought up questions about the ethics of using visual devices for shaping culture or changing behavior.

Guest Lecture: Tom Moore, Los Angeles Public Defense Attorney

Defense lawyer Tom Moore was a memorable guest. He frequently represents individuals accused of violent crimes; many of his clients come from traumatic backgrounds. His stories brought to us the importance of empathy. Tom humanized clients by touching them on the shoulder in court and speaking of their lives. He talked about the basic right of a fair trial even for those who cannot afford representation. Ruth said, “Having Tom Moore as a guest was extremely moving for me.” Cassie said, “He’s the most compassionate person I’ve ever met; he showed us a level of compassion that I wasn’t’ sure was even possible. It’s always helpful to challenge fixed ways of thinking.” After Tom’s visit, students often pointed out alternate perspectives during critiques.

Visual Documentation

Students were asked to take notes in the form of visual documentation, recording their thoughts and insights during Tom's lecture. Visual documentation involves freeform sketching in combination with writing while avoiding rigid structure. During the LEAP Symposium (a three-day gathering hosted at Art Center byDesignmatters, during which 150 thought leaders in design for social innovation gathered to explore the future of careers in this emergent space) we headed a team of students who took visual documentation of what was discussed, grappled with, discovered, and developed and create a workbook about the symposium. This workbook was used as a guide for future discussions. During this in-depth participation in the symposium, we discovered that there are growing opportunities for illustrators in the field of design for social innovation (Crow, 2006).

Encouraging Autonomy

In the beginning, students presented the Human

Rights Project with loose parameters. It was important for us as instructors to facilitate student questions and to be comfortable ending a discussion without clear resolutions. We often stepped back

and facilitated the students’ open-ended questions pertaining to students’ sources, of their statistics and the choices of their imagery. Student-led critiques encouraged autonomy. By the

end of the term, students developed their own projects and advocated for them with effective presentations that were backed by research. A student named Ashley describes this philosophy as

“self-directed projects with a social theme and tools to analyze imagery critically.”

Messages with a Personal Connection

We also encouraged our students find a personal connection when problem solving, igniting a passion to find unique and relatable solutions that have meaning for the artist. Adriana made a video designed to be disseminated online that raised awareness of oil drilling in remote areas of her home country, South America. Estella created a doll that could be explored for messaging that was directly related to a negative physical experience she had as a child. The presentations were moving and the class connected.

URBAN RESPONSIBILITY PROJECT

Students were asked to explore their own neighborhood and look for problems they felt could be improved or fixed through design.

Participatory Design

It was important that projects involved collaboration between the illustrator and the end-user during the design process. We referred to this exchange as “participatory design” as used by Austin Center for Design (Kolko, 2012). Cassie discovered that her local public library lacked outdoor signage. She found that many local residents didn’t even know the library existed. After meeting with the librarian and talking to English and Spanish speaking patrons of the library, she created bi-lingual signage For the text in Spanish, she used Google Translate and then tested the legibility with Spanish speaking friends and the end client. She explains that this particular project helped prepare her to problem-solve and work with the needs of her community. “[I had to] find problems in my local community of Pasadena and act on it. This was the first time I had to speak with individual to help them address real problems for an illustration class.”

Client/Designer Relationship

The class took a field trip to the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles, to see an exhibit that used illustration as a means to educate. The principal of the design firm hired to create this exhibit and the museum staff were on hand to discuss the design process from start to finish. The students engaged in a real world account of the client/designer relationship, including how ideas were generated, what research was done and how problems were solved and overcome.

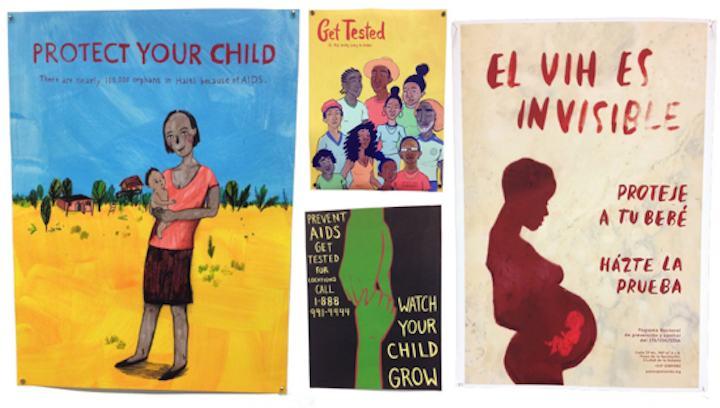

CULTURAL SENSITIVITY PROJECT

Students were asked to create a poster encouraging the use of condoms for birth control for a specific location in the Caribbean.

When our Ideology conflicts with the Client Brief

This assignment had many levels of complexity. In researching condom use in the Caribbean, students found belief systems and social behaviors that contrasted with their own. One student wanted to address the stigma against homosexuality and chose to create a poster advocating tolerance. Another student was Catholic and had a problem promoting the use of birth control because it was against her religious beliefs. She chose to create a poster educating pregnant women on how to get tested for HIV. During the critique students learned how hard it is to suspend judgment and put aside personal beliefs. One student recognized, “this project really forced me to re-evaluate my personal biases and to have an open mind.”

Recognizing Western Cultural Bias in Image-Making

During the poster critiques, we discussed how Euro-American illustration stylizations might affect the messaging. The class continued to struggle with their assumptions. In particular, we discussed how one student's use of a floating hand could be interpreted as a reference to corporal punishment, still legally used in over 33 countries today. Another student's illustration style utilized a contemporary western way of rendering faces that could be misinterpreted to signify that the noses were missing. The discussion continued about various ways images are interpreted around the world, by generation, religious beliefs, culture and degree of education (Werner, Maxell, Thurman. 2013). The students learned they had to essentially wipe their minds clean western cultural assumptions- from directional symbols, and left-to-right, up-down reading to the visual metaphors they use in their daily lives (Clarkson, Jonson. 2002).

Localizing Visual References

In this stage students were required to back their image choices with mood boards and the class came to develop their own style of research packets. Lori’s research boards included her name, her goal, images, and color palette, evolution of sketches, cited statistics and bibliography. In order to reduce confusion, The Peace Corps advises testing visuals, using local likenesses, and making revisions for clarification (Peace Corps, 1985). The poster messaging improved, as the student’s research narrowed their message to a particular city and its specific demographic. Having research to back up their choices gave the students more confidence in presenting their work.

When

Participatory Design is Missing

Without working directly within a community, more questions were raised than answers. The students discussed how context and location could change the message of an image. Some students recognized the handicap of not working on the messaging with the community itself, and the students noticed their design disadvantage of not testing the messaging with the people who would be seeing their images. Our student Ruth said, “The Cultural Sensitivity project was the most challenging. It had restrictions, limitations. It made me dig deeper and challenged how I solved problems.” In cultural sensitivity projects, students could greatly benefit from in-class guests, field trips, or working directly with a community.

IMAGES FOR CHANGE PROJECT

Students were asked to research an area/problem of interest, write and present a proposal, create a solution then formally present their proposal to visiting guests.

CRASH Awareness in Imagery

A field trip to Target challenged the students to become more aware of how images in the media categorize people to promote and sell products, for example using the acronym CRASH-Class, Race, Age, Sexuality, and Handicap (O’Shaughnessy and Stadler, 2006). The class began by exploring the toy aisles where stereotypical gendered imagery is most prevalent. They were asked to record their observations. As was expected, the aisles for girls were dominantly pink and the boy's aisle dominantly blue with a small section tucked away in the back with gender-neutral toys painted orange. Very little packaging showed both a girl and boy playing with a toy together. Nearly every child shown was white and representation of diversity was almost absent. We discussed, as illustrators whose imagery is disseminated into mass culture, why it is important that we do not unthinkingly recycle gendered images.

Disagreement and Discussion

Open critical dialogue between classmates and instructors became the backbone to the development of this class and the students and their work. As Cassie pointed out “We do a lot more discussion and research than image-making, and we practice pitching our ideas to clients - neither of which we practice in any other illustration classes.” Because problems and solutions were complex, discussion helped everyone understand what the visual outcomes could be. The conversations were often intense due to heavy subject matter but by the end of the term, the students understood the messaging of agency and hope.

Effectively Presenting to a Client

Most Designmatters classes include a project with real clients, presentations and deadlines. In this class we knew it was important to introduce the experience of presenting work to a client. We invited members of the faculty to act as "clients" to listen and critique the final presentations. Cassie pointed out “I’ve found my weaknesses are in doing research efficiently and speaking comfortably during presentations. I’m glad that I discovered those weaknesses before entering the professional world.” Following this class, Cassie has gone onto proposing projects within her community, initiating fund-raising for her projects and will be presenting at ICON8, The Illustration Conference.

Lori, the most junior student in the class, created a standout final project. She worked on re-imaging Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar for both blind and visual readers so that they could read together using textures, bright colors and Braille. She said, “Illustrating a Braille friendly book that can be read by visual and non visual children was a project I loved. I was able to run free with my own idea and I’m able to walk away with a deeper understanding of how to design as an illustrator.”

The Benefits and Pitfalls of Team Teaching

Designmatters-based classes are often taught with more than one instructor. Multiple perspectives should be welcomed to fully explore atypical solutions. Being able to handle differing opinions is a crucial skill needed in this growing field. Working with teams usually brings out differences. We found that problem solving with diplomacy is a skill that can be learned through practice. Students must be able to present a considered proposal, hear varied feedback, and be confident to make informed revisions. According to Stanford Business Graduate School of Art, the drivers for social innovation are a “cross-sector fertilization” that involves“exchanges of ideas and values, shifts in roles and relationships” (Chang, 2000).

Conclusion

We have seen first-hand how excited students are to use their work for change, to find some meaning in their work. Creating an introductory class geared specifically toward illustration shows students what they can do with their skills. Smart Image/Social Impact prepares illustrators for using critical thinking and visual skills to collaborate with people of different backgrounds and knowledge. They learn to tackle challenging social issues using open-ended, problem-solving skills fostered by empathy and ethical awareness. They learn how to research smartly and how to prepare persuasive presentations.

Design for Social Impact is an exciting new field for illustrators to carve out a participatory role. Especially now, as companies and non-profits search out innovative designers and to improve business practices or tackle social issues. Access to social innovation classes creates illustrators who are empowered to create the career they want, rather than doing solely what is expected of them.

Perhaps we should take our student Cassie’s advice, “It (may be) the one class that will focus on applying your illustration skills to tackle current issues. It’s an elective now, but it should be required.”

Bibliography

Designmatters. (2006) About. [Online] Available from: http://www.designmattersatartcenter.org/. [Accessed: 2014].

LEAP Symposium. (2013) A Focused Conversation. [Online] Available from http://leapsymposium.org. [Accessed: 2013].

The Center for Social Innovation, Stanford Business Graduate School of Art. (2000) Social Innovation. [Online] Available from http://csi.gsb.stanford.edu/social-innovation. [Accessed: 2013].

O’Shaughnessy, Michael and Stadler, Jane. (2006) Media And Society and Introduction, third edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Werner, D., Maxell, J., Thurman, C. (2013) Where There is No Doctor; A Village Health Care Handbook. Revised Edition. Berkeley: Hesperian Foundation.

Clark, M., Harvey, M., Nest, K., Wilburn, M. (1985) Oral Rehydration Therapy and the Control of Diarrheal Diseases Training For Development. Session 18-Adapting and Pretesting Health Education Materials on ORT for Controlling Diarrheal Diseases. Oak Park: Peace Corps/CHP International.

Clarkson, R., Johnson, H. (2002) Production Manuals for Non-Literate Farmers: Handbook for Development Workers, Part 2-Illustration. Scotland: Institute of Ecology and Resource Management, University of Edinburgh.

Crow, D. (2006) Left to Right/The Cultural Shift from Words to Pictures. Switzerland: AVA Publishing SA.

Kolko, J. (2012) Wicked Problems: Problems Worth Solving, A Handbook and Call to Action; Austin: AC4D Austin Center For Design.

Biographies & Experience

Esther Pearl Watson, Associate Adjunct Faculty, Art Center College of Design, has an MFA from CalArts and is the author of the comic Unlovable for Bust Magazine and Fantagraphics Books. Watson’s illustrations have appeared in many newspapers and magazines including New York Times and Lucky Peach. Watson’s paintings have been exhibited at The Santa Monica Museum of Art, the Oakland Museum of California, Suzanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. Watson has lectured extensively including “Teaching Design Responsibility and the Millennium Dream Project,” UNESCO NGO/DPI CONFERENCE, Paris, France. She has taught at Oxbow Artist Residency, The Lexicon of Sexicana at Columbia College in Chicago, and will attend an Artist-in-Residence through GrafikiensHus at the old royal barn of Gripsholms Castle in Mariefred, Sweden. Watson Currently lives in Los Angeles and teaches at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California.

Martha Rich, Adjunct Assistant Professor, Fashion Institute of Technology, is a Philadelphia-based artist and teacher. She graduated from Art Center College of Design with Honors and received an MFA in painting from the University of Pennsylvania. Rich’s commercial work has been used in music videos, advertising, magazines, book covers and more. Her paintings have been shown in galleries across the country and internationally. In Philadelphia, Rich taught at Tyler School of Art, Drexel University and University of the Arts. She’s currently teaching in the MFA program at the FIT in NY. Prior to relocating to the east coast, Rich taught at Art Center College of Design within the Illustration and Designmatters departments. She has recently returned to Art Center to team-teach (with Watson) the newly developed Smart Image, Social Impact class that again partners the Illustration Department with Designmatters to introduce the Designmattersconcentration to illustration students. She served as President of ICON6: The Illustration Conference.

ICON: The Illustration Conference is committed to providing a forum for an ongoing dialogue that serves the illustration, design, publishing, advertising, and academic communities. Its purpose is to provide a platform for the most influential illustrators and industry leaders to address, in a timely manner, the most pervasive issues facing the profession. Illustration Conference (ICON) is a 501 C-6 nonprofit organization of illustrators and is an entity in itself. ICON remains the only national conference specifically for illustrators and the graphic arts community providing an unprecedented forum for the creativity, inspiration and drive that captivates the profession. ICON8 Education Program is chaired by Rick Lovell, Illustration Program Coordinator, Savannah College of Art and Design.