Photographer Profile - Lyle Owerko: "Mongolia is sort of the last frontier"

|

|

|

Sometimes not knowing where you are on a map is a good thing: Owerko was in fact right where he wanted to be. Getting lost in the middle of nowhere in Mongolia was more or less the point of his trip.

He’d started thinking about traveling to Mongolia in 1999, when he was working as a designer at an advertising agency in New York and shooting pictures and music videos on the side. “I had had enough of being in a cubicle 16 hours a day, grinding out ads, and I decided to go traveling,” he says.

He didn’t get to Mongolia then. Instead, he went to Southeast Asia and Africa, where, he says, he taught himself photography. “I shot only transparency film so that I would get really good,” he notes. He returned to New York just in time for a tragedy.

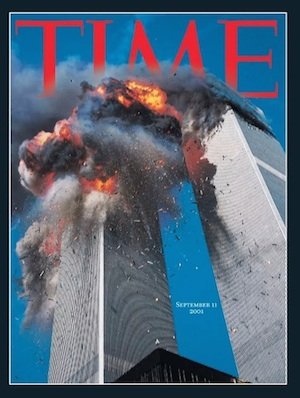

On the morning of September 11, 2001, Owerko was in his Tribeca apartment, jet lagged and unable to sleep, when he heard an unfathomable sound. An American Airlines jet had just hit the World Trade Center’s north tower. He grabbed his camera bag, with a 35mm SLR and a medium-format Fujifilm GA645zi camera, and ran toward the disaster. There he used the SLR with a 400mm lens to photograph people jumping from the burning tower.

Then he saw a second plane approaching the south tower. Using the medium-format camera, he shot two frames as it hit. One of the photos ended up on the cover of Time magazine. In 2005 the American Society of Magazine Editors ranked it among the 40 most important magazine covers of the last 40 years.

Such was the beginning of Owerko’s professional photography career. He might have gone on to become a globetrotting photojournalist, if not for some advice from a friend he’d made — Magnum photographer Gilles Peress. “He said, ‘You’ve already had the cover of Time. Now maybe you should reinvent yourself,’” Owerko recalls. Following Peress’s advice, Owerko returned to Africa as part of economist Jeffrey Sachs’s Millennial Promise initiative documenting the lives of the Lau people of Sauri, Kenya.

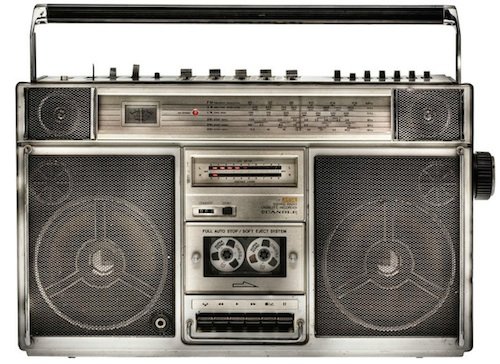

In 2006, back in New York, he reinvented himself again by starting a personal fine-art project about vintage boomboxes. He had been collecting specimens since the 1990s and was fascinated by the cultural history they represented. The result was The Boombox Project, an acclaimed book from Abrams and a body of work that has become a favorite with collectors.

“It’s like the hit album that you can tour on forever,” Owerko says.

After the boombox book came out in 2010, Owerko decided it was finally time to go to Mongolia. What he found once he got there three years later was everything he’d hoped for and something completely unexpected.

Mad Max Imagery

“It’s a magical place where you can be all day and not hear an airplane or see a contrail,” he says. “Mongolia is sort of the last frontier.”

Owerko, who grew up in Calgary, Canada, says the landscape of Mongolia “tapped into the journeys of my youth through western Canada with my dad.”

“I went to school with kids from the Sarcee and Blackfoot tribes,” he says, “and going to Mongolia fit into the Canadian-wilderness-meets-Farley Mowat upbringing I had.”

The least densely populated country in the world, Mongolia has seen tourism climb since the 1990s while becoming a go-to destination for photographers drawn by its rugged landscapes and the nomadic culture of its people. Among the attractions are the Kazakhs, who have been hunting with golden eagles in western Mongolia for thousands of years.

When Owerko arrived in Mongolia, he was confronted by a reality that sparked his considerable curiosity. He says he was determined to avoid the trap of cultural imperialism — or, as he puts it, “telling bullshit backstories about trekking off into the wild to document these indigenous people.” Rather, he wanted to capture the sense of adventure and strangeness he experienced at the airfield in the middle of nowhere.

“The imagery is almost post-apocalyptic — like Mad Max imagery,” Owerko says. “You go there and you see a guy on a motorbike wearing a Russian army overcoat with an eagle riding on back. I couldn’t make that up. I couldn’t style a weird picture like that. I didn’t want to photograph indigenous people wearing traditional outfits — I wanted to photograph that guy with an eagle on a motorbike. It doesn’t get much more badass than that.”

He shot portraits with a Hasselblad H4D-50 and action photos with a Canon DSLR. The look of the finished images reflects Owerko’s conception of a mythology in which eagles serve as the connection between earth and sky, between man and a higher life order.

“In post-production I pushed everything so that the skies went white and yellow, and I introduced jewel tones and the color purple into the images because purple is the color of royalty, and the eagles there felt so regal,” he says.

A New Eden

Owerto says he grew up painting and drawing; it wasn’t until his late teens that he became interested in photography — and then only as an “information-gathering tool.”

“The camera was just a sketching device for me,” he says. “Photography was a way for me to annotate life.” He moved from Canada to New York City to get his MFA in design from the Pratt Institute. But, he notes, he always carried around a Ricoh GR1v point and shoot in his pocket.

“I would take pictures on my way to work and on my way home,” he says. “I shot the ’90s that way — street stuff, saving negatives, just building and building, then eventually I bought some lights and started experimenting.”

The images Owerko made in Mongolia bear comparison to his work from Africa in the 2000s — both avoid cliches in order to capture an unsentimental portrait of a contemporary culture. “When I was in Africa,” he says, “I was like, ‘I love the idea that the guy I’m looking at is wearing a wrist watch and has a beaded case for his Blackberry. It’s a mix of traditional and current.”

His work has also invited comparisons to that of Peter Beard, who has come to be a friend and mentor to Owerko. “He was really fascinated with my 9/11 work, and he always challenged me as a young photographer,” Owerko says.

In 2008, Owerto penned an appreciation of Beard for Photo Icon magazine that puts his own photography in perspective. “Peter’s Africa does not exist anymore,” Owerko wrote. “We can search for it, we can climb for it, we can drive for it, but it’s not there. The innocence of the African Eden is gone. We can only hope to maintain what remains of its great swaths of nature. Each trip I make to Africa, I feel like I am running into a burning house, taking pictures of vanishing beauty.”

Owerko found his Eden in elsewhere. “What I tell people is that if Peter Beard were coming up now, he wouldn’t be in Africa. He’d be in Mongolia,” Owerko says.