Photographer Profile - Andrew Kaufman: "I wanted to create this definitive documentary about these men and women"

|

|

|

This summer, notes photographer Andrew Kaufman, an event took place that could affect every person on Earth. It didn’t get much attention.

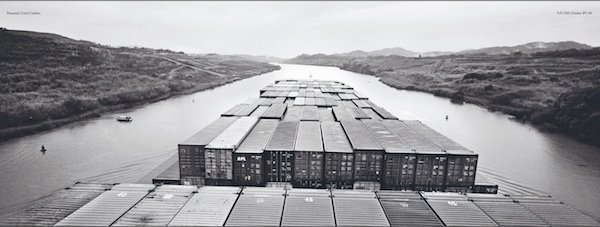

On June 26, the newly expanded Panama Canal opened for business, marking the completion of a decade’s work. The expansion doubled the capacity of the canal by widening and deepening its lanes for a new generation of huge cargo ships. In addition, a new lane of traffic was dug, allowing more ships to pass through. It was a monumental feat of engineering: The amount of steel used in construction could have built 29 Eiffel Towers, noted the Washington Post earlier this year. The Empire State Building could lie down and fit into just one of the three chambers in each of the new canal’s locks.

The affect of the canal on world trade is already being felt. For instance, it’s been estimated that 10 percent of the shipping traffic from Asia to the US will shift from the West Coast to the East Coast because of the reduced costs of going through Panama. Ports from South Carolina to Bayonne, New Jersey, are making plans to dredge and heighten bridges to accommodate the new, larger ships coming their way.

Beyond that, the canal’s expansion could have far-reaching political and environmental implications, notes Kaufman. “For one thing,” he says, “it could actually change the planet’s weather patterns because of the deforestation involved with the expansion.”

The US media, however, greeted the new canal with what was essentially a shrug. A big ditch — even a monumentally big ditch — wasn’t as exciting as this summer's political conventions and nightly tweets from Donald Trump.

For Kaufman, however, the canal was much more than a ditch. He was on hand for the first day of its construction in 2007, and he spent 10 years chronicling its progress. He kept a journal filled with his pictures and notes about the work and the people of Panama, who he grew to admire. That journal has now been reproduced as a book called The Isthmus: A New Path Between the Seas.

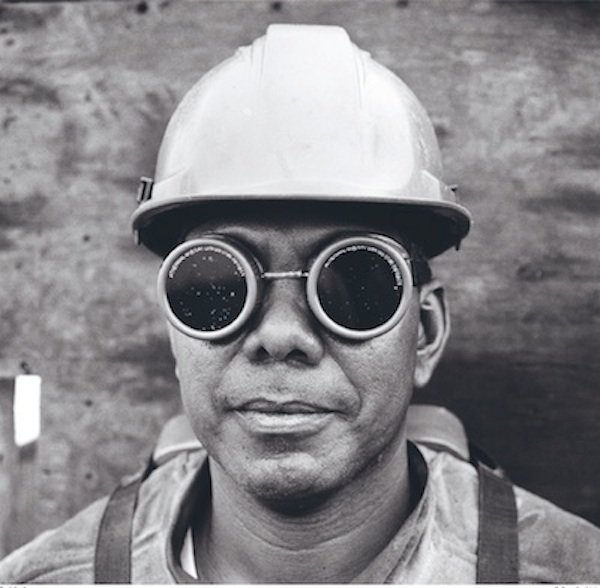

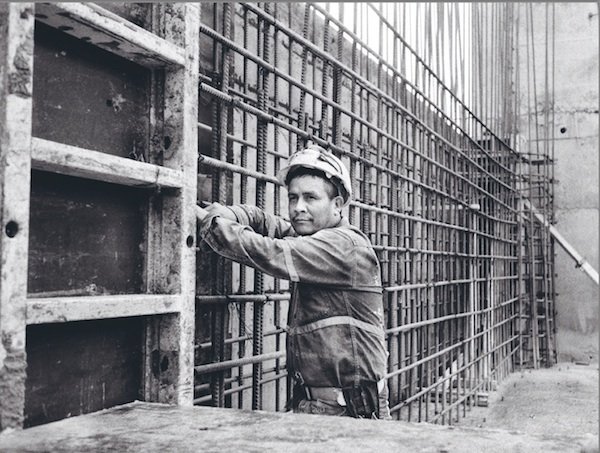

“I wanted to create this definitive documentary about these men and women who expanded the canal and changed their country and its landscape,” he says.

Kaufman is based in Miami, and earlier this fall he showed the new book to an editor at Vice magazine’s office there. For Kaufman, the story of the Panama Canal expansion is filled with drama and daring, and he thought the editor might be interested in featuring it.

“But he wasn’t sold on it,” Kaufman says. “He asked me, ‘Why should young people care about this?’ And I said, ‘Because it will change the way they shop.’”

Historic, Heroic and Herculean

The first ship through the new 48-mile-long Panama Canal was the mammoth Cosco Shipping Panama, a vessel holding 9,472 containers. It entered on the Atlantic side of the canal, made its way through one of the new locks, went on to man-made Gutan Lake and the Culebra Cut — an artificial valley dug in a tree-covered mountain ridge — and continued to the Pacific Ocean.

Before the flooding of the canal’s new locks, there was an open house for Panamanians at which people were allowed to stand at the bottom of the new Cocoli locks, 33 meters below where the water would later stand when the expanded canal became operational.

“The line to get in was a thousand people deep,” noted Kaufman in his journal.

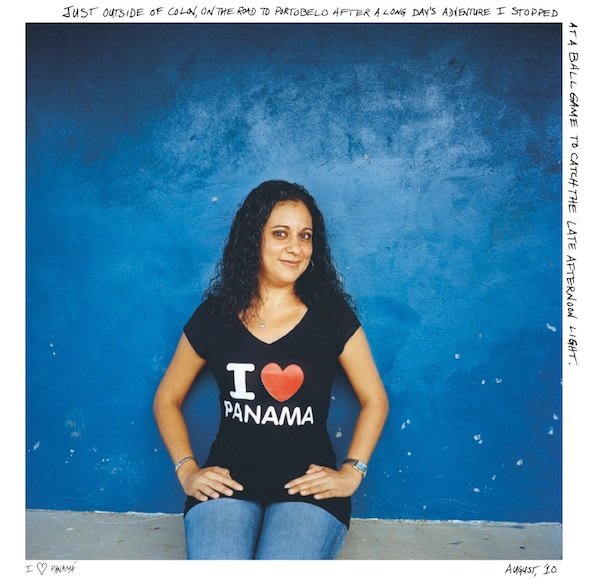

From the beginning, it was the Panamanians as much as the canal that interested Kaufman, an editorial and commercial photographer whose his pictures have appeared in Time, Newsweek, Fortune and other publications. He first went to Panama in 2004 on a surfing trip. “I’d read about the idea for the expansion, and I spent 30 days seeing the country,” he says. “I visited the canal, but I also visited all four corners of Panama.”

Right away he formed an ambitious idea about documenting the country. “I wanted to do a historic and heroic FSA-like project, something like Walker Evans or Lewis Hine did. Making

the Panama Canal bigger just seemed so Herculean an idea,” he says. Back in the US he began spreading the word among magazine photo editors that he was looking for assignments in

Panama.

“Newsweek sent me to Panama on a job. So did Conde Nast Traveler Italy and Endless Vacations magazine, “ he says. “Being based in Miami, it was easy for me. It’s only a two-and-a-half-hour flight.”

Time sent him to there in 2006 to cover the nationwide referendum in which Panamanians voted to approve La Expansión. The project’s plans mandated that 90 percent of workers on the construction project would be Panamanian, a huge economic boost in a country with at least 20-percent unemployment.

“All the time I was there shooting color for the magazines, I was also shooting black-and-white work for myself,” Kaufman says. Eventually he found that the story he was telling about the expansion project was actually two stories — one about El Canal and one about the country itself.

Two Stories That Are One Story

The two stories of Panama are reflected in his book’s double-sided design — one side features Kaufman's images of the canal and the other his photos of Panamanians.

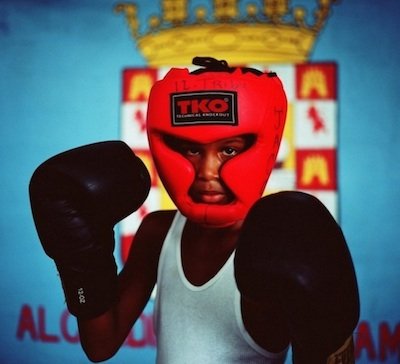

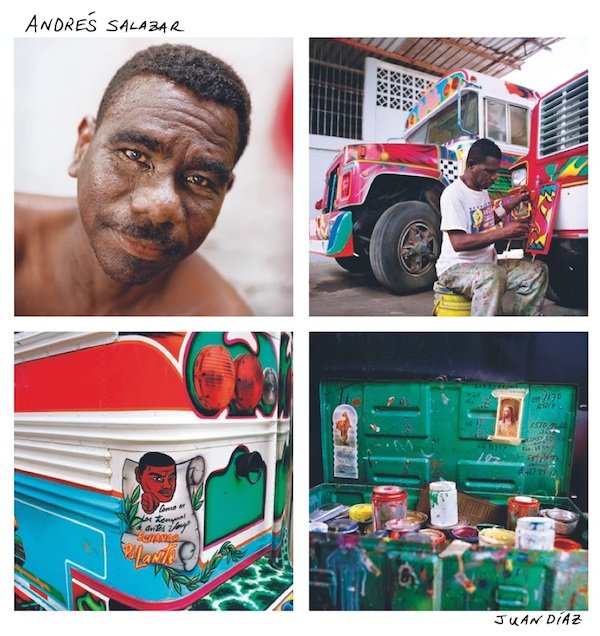

“What was very interesting is that as the canal was modernizing, so was Panama. It was that story that I wanted to tell, and the double-sided book made a lot of sense,” Kaufman told the Washington Post's In Sight blog recently. He photographed the celebrated buses of Panama — creaking old American school buses painted and adorned by local artists — which were being replaced by sleek new models. He also photographed inside the Panamanian boxing gyms that have turned out so many noted fighters.

Kaufman made 24 trips to Panama over the decade of the canal’s expansion. “In the last year it really became my full-time job because I needed to photograph the final stages of the expansion,” he says. “There were a lot of important milestones to document.”

He notes many of the particulars about the new canal in his book — that engineers devised a new lock system that will save more than half of the fresh water discharged when ships pass through; that 5,000 animals were relocated during the construction; that over 900 hectares of land have been reforested; that archeologists found 8,000 artifacts during the dig, including a 16th-century Spanish dagger and pre-Columbian arrowheads.

He also includes his photograph of the construction’s first excavation in 2007. “There were 50,000 people on a hillside in the rain watching,” he says. In end, the two stories were really one story — the story of the Panama Canal’s expansion is the story of the people who voted for the project and then made it a reality.

“It’s amazing to think about what they accomplished and what it means to them,” Kaufman says. “On the day the canal was inaugurated this summer, I photographed a hand-painted sign in the lobby of the control tower of the Agua Clara Locks. It said, ‘Nosotros si construimos el canal’ — ‘Yes, we built this canal.’”