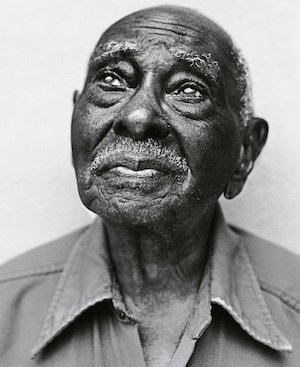

Photographer Profile - Paul Mobley: "When somebody who's 105 tells you about the joys and tragedies in their life, you listen"

|

|

|

Paul Mobley has photographed hundreds and hundreds of faces — movie stars' faces, comedians' faces, musicians' faces, athletes' faces — and he knows what features make for a great portrait.

“Sunken eyes, big eyebrows, big chins and big ears,” he says. “I really love big ears.”

Mobley, who splits his time between Los Angeles and New York, spends most of his working life shooting portraits for magazines (People, Esquire, Rolling Stone) and advertising work for commercial clients (Delta Airlines, Chevrolet, Max Factor, and John Deere). But he has also taken on a number of personal projects that have led him far from the studio for long periods. One of them — a two-year journey to some 300 farms and ranches across the US, turned into the 2008 book American Farmer: Portraits from the Heartland. It was while visiting farmers in their homes that he stumbled onto another idea.

“Every once in a while, I’d pull in to meet the family, and there would be grandpa sitting in the kitchen, or out in front driving a tractor,” he says. “I’d ask, ‘How old is grandpa?’ And the answer would be, ‘Oh, he’s 103 now, and still going strong.’ I always took time to photograph the grandpas and grandmas. Then I’d get back to the studio and say, ‘Oh my god, look at these faces!’ I was just fascinated by everything from the curve of their spines to the shape of their hands and the wrinkles on their faces. So I thought, wouldn't it be great to do a book of portraits of centenarians.”

Rizzoli agreed, and the result is the new book If I Live to Be 100, which features 85 of Mobley’s black-and-white portraits of centenarians. The book is partly a travelog: Over the course of two years, Mobley traveled to each of the country’s 50 states to find his subjects. But you may as well think of it as a journey through time.

There are 70,000 people in the US who have lived to be 100 or more — a frankly arbitrary mark we use to distinguish those who have challenged the norms of mortality. Numbers are a way for us to track time and measure our allotment of it. Recently the New York Times spoke with Dr. Jan Vijg of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, who published an article in the journal Nature proposing that humans have hit the upper limit of longevity at around 115. The record for human longevity still belongs to Jeanne Calment, who passed away in a nursing home in France in 1997 at age 122.

In his travels, Mobley photographed a 114-year-old, a couple of 115-year-olds and one vibrant lady who was closing in on 117. One of the 115-year-olds, Besse Cooper of Monroe Georgia, shook Mobley’s hand firmly when they met and told him, “There will be no pictures taken if I can’t wear my pearls.” She’d been wearing them since she was a young women; they were, her son said, her good-luck charm.

“She was a diva at age 115, and it was just the best,” Mobley says.

Numbers, at any rate, are only one way of keeping track of time. There’s another way, and it doesn’t come with limits. Mobley’s portraits ask us to consider what age is: an accumulation not of days but experiences etched into fascinating faces. In his pictures, age is knowledge.

“When somebody who’s 105 starts to tell you about the things they've learned and the joys and tragedies in their life, you listen,” he says.

The Secrets of Long Life

You also don’t spend two years photographing centenarians in 50 states without asking them for tips on how to beat the odds.

“I asked all the time, ‘What are the keys to long life?’” Mobley says. “I recently looked at the notes I kept, and what stood out was how different the answers were.” One person told him not to go to the doctor. He was also advised to get a dog. Others told him the secret was having things to look forward to. For one of his subjects, Goldie Steinberg, that was the nightly phone call she received from her son at precisely seven o’clock.

“He did that for 50 years,” says Mobley, “and she lived to be 114. The one thing I took away from it all was that long life is not all about genetics. When we talk about doing everything in moderation and exercising and not getting too stressed out, those are really important.”

Mobley, who says he hates airports, was determined not to stress over travel when he launched the project. “Rizzoli said I didn’t need to do all 50 states, but I thought it made a better story,” he says. Instead of flying here and there, he hit the road with his wife Suzanne and dog Jesse in an RV loaned to him by Airstream. An assistant hired by Rizzoli provided him with biographies of potential subjects.

“I did it in segments — a week here, 10 days there,” he says. “If I was on the road and a commercial job came up that I needed to do, I’d leave Suzanne and the dog and fly off to do it, then come back.”

His gear consisted of a Hasselblad H5D and Canon 1Ds Mark III, along with Profoto and Kino Flo lights. Mobley’s lighting etches the wrinkles deeply into the faces of his subjects while imparting a glow of dignity. “The idea was to do the opposite of any kind of post-production,” he says. “I wanted all those wrinkles in the pictures. Any retouching would wreck it.”

Time Well Spent

The photo sessions often took longer than he expected because his subjects had so much to say. The elderly, often ignored and left unseen, are like vaults filled with stories, says Mobley. His cameras and his time were the keys to opening them up.

“I could do the picture in 20 minutes, 30 minutes, but they wanted to sit around and talk,” says Mobley. “They wanted to share their lives and their stories. Some of them had outlived their own children, so there was loneliness.”

Listening to them, Mobley says, was time well spent. There was a period in his life, he noted in a recent interview, when he became fed up with photography. “I had gone eight years without a significant break in my commercial work, and photography had become a very stressful thing. I had gotten to a point where I’d put a camera in my hands and they would start shaking,” he said.

He decided he needed to spend a summer with his wife at a cabin in Michigan, where he grew up. Then one day at a coffee shop he saw a group of farmers and couldn’t take his eyes off their faces. “They were beat up and muddy, and I saw them and thought, ‘Really? The photography gods will not give me the summer off?'”

He photographed the men in the coffee shop, and the experience reignited his love of photography. He went on to shoot his farmer project, which in turn led to his book on centenarians.

“In the end, it was my interactions with the farmers, these salt-of-the-earth honest people, and the centenarians, who’ve lived such incredible lives, that was worthwhile,” he says. Filling his allotted time in the presence of such people, he says, “is the best thing about what I do.”