Photographer Profile -- Nick Brandt: "We are living in the antithesis of genesis right now"

|

|

|

He was just warming up. Brandt also decried the disappearance of democracy in an America that, as he put it, “is increasingly more insane as we career toward a Trump presidency.”

“So just as you think the US cannot get any more fucked up and stupid, here it comes,” he said. “None of us thought Bush would be elected. But he was. And then McCain brought in Palin, and we thought, ‘Jesus Christ, who the fuck is going to take this woman seriously?’ But she was, even though she can’t even speak a sentence. It’s like English is her second language, but she doesn’t have a first language.”

He paused. “I love the opportunity to go off on America now and then,” he said. “By the way, you can quote me on every single thing I just said, including the curse words, because I really don’t give a fuck.”

Why should he? Brandt has spent the past 15 years documenting in increasingly elegiac photographs the wild animals of East Africa — species, he says, that are being “destroyed by the hands of man.” The subject of his work is nothing less than the end of nature, and if you can’t get worked up about that, then what?

“We are living in the antithesis of genesis right now,” he writes in his new book. “All those billions of years to reach a place of such wondrous diversity, and then in just a few shockingly short years, an infinitesimal pinprick of time, to annihilate that.”

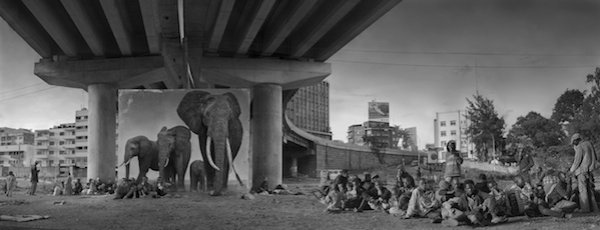

His new book is a jeremiad and, he says, a “call to action” meant to focus the world’s meandering attention on the destruction of landscapes and species before they are gone. But it does so in a conceptual way. As the New Yorker noted in March, Brandt set out to decontextualize his own wildlife photography, which he has called “unabashedly idyllic and romantic.” He produced prints showing the animals in life size, placed them in large panels, and then placed the panels in locations where the animals once roamed but are now factories, building sites, and roadways. Then he photographed the scenes.

The work marks a turn in Brandt’s own thinking. “It’s an attempt to explore the subject in a more direct, emotional, and political way than the previous work did,” he said.

Behind the Scenes

Brandt will be one of the featured artists at this year’s LOOK3 photography festival in Charlottesville, Virginia, which runs from June 13 to 19. Three of his life-sized images will be on view, and he will be interviewed during an evening projection by the photography critic Vicki Goldberg, who once wrote that his photographs of animals “convey a rare sense of intimacy,” as if he knew the animals and “had invited them to sit for his camera.”

“He is on firm footing in the areas of beauty, awe, and sympathy,” wrote Goldberg, “and he navigates a sure course across the diverse regions of portraiture, emblem, environment, nostalgia, narrative, and entropy.”

Brandt, an Englishman, moved to the US in 1992 and built up a career shooting music videos. It was while directing the video for Michael Jackson’s “Earth Song” in Tanzania that he first encountered the wildlife of East Africa. That was in 1995; by 2001 he was back in Africa working on a trilogy of books, the first of which, On This Earth, was published in 2005. His second book, A Shadow Falls, was published in 2009, and he concluded the series with Across The Ravaged Land, published in 2013. Taken together, they represent his own journey of discovery and a maturing viewpoint.

“It began as a sort of honeymoon period when I was photographing a paradise, because I was completely in awe of that world,” he says. “Then it became darker and darker and more and more melancholy — more so than even a pessimist like me could have thought possible. Finally the trilogy ends with images of the tusks of elephants killed by man.”

The idea for the new book came to him in 2014. “I always felt that history in school was so boring, just learning about treaties and battles,” he says. “For me, what would have brought it to life was the idea of finding out what happened on the very ground you were now standing on. That’s what I wanted to do in the book, to show the animals that once stood on these places.”

The book ends with a behind-the-scenes look at the project — something Brandt didn’t want to include at first. “I get irritated at the Making-of-obsessed media in which we increasingly live, and rightly or wrongly, believe in preserving the mystery of creation,” he writes.

He changed his mind after showing his finished panoramas to people, some of who asked if he had added the animals into the landscapes with Photoshop. He felt the need to show that these were real places — places he had been to with a crew of some 20 men carrying 30-foot-long panels in 100-degree heat.

Man and Nature

Of all the locations he shot in, two stand out in his memory.

One of them was a vast dump site, where he and his crew spent 10 days working. “But we got to go back to our hotels every night, and then later back to our comfortable lives,” he says. "Meanwhile there are people who spend their whole lives in that toxic environment. The dump is the kids’ playground, and they get their food from the rotting garbage that arrives every day.”

The other location that stays with him was a highway underpass where he photographed a huge print surrounded by young men high on glue. “There’s no societal support for them — no one is going to come along and help those kids out,” he says. “Their motor control is beginning to go at a very young age, and I don’t see how they will ever recover from it.”

Interestingly, those two shoots produced what Brandt considers the best images in the book, “Wasteland with Elephants” and “Underpass with Elephants.”

“I don’t know if that’s a coincidence or not,” he says.

The pictures make it clear that the issues Brandt raises in Inherit the Dust go beyond poaching. We see that the destruction of wildlife and nature results in the destruction of man.

“This body of work appears to suggest that there’s no hope — the images are unremittingly dystopian, almost to the point of being post-apocalyptic at times,” Brandt says. “It’s beyond my skill set to include a semblance of hope within the photographs. But there is hope. I just can’t capture it. Instead I have to talk about it, both in the written word and in interviews.”

Sometimes he rants.