Photographer Profile - Macduff Everton: "The Yucatan has shaped my life"

|

|

|

“And that was absolutely true, it really was,” says Everton.

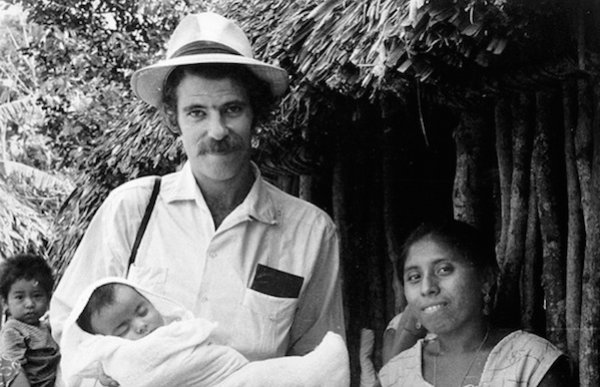

Everton is best known as a travel photographer — his pictures have appeared in Conde Nast Traveler, Smithsonian, Outside and other magazines, as well as in advertising for Delta Airlines, Rolex and Patagonia. But throughout his long career, he has been consumed with the Yucatan and the Mayan culture. He made his first trip there in 1967, when he was 19, and kept returning to photograph the people he met, descendants of an ancient race who lived apart from the rest of Mexico, with their own traditions and language.

It took him 25 years to produce his first book, The Modern Maya: A Culture in Transition, which was published by the University of Mexico Press. Twenty years after that came The Modern Maya, from the University of Texas Press. The book was a work of visual anthropology and a personal chronicle in which Everton captured the changing the world of the Yucatan’s indigenous people by documenting the lives of a number of families over several generations. It also included a 180,000-word history of the Mayan culture written by Everton.

“My greatest wish with the book was to present it to these people, because it really was theirs — it was about their lives and their history,” Everton says. “The problem was that all the text was written in English.”

Now Everton is bringing out a Spanish translation of the book, Los Mayas Contemporáneos Incidencias de Viaje y Amistad en Yucatán. He financed the project through private funding and produced it with the help of a Spanish-speaking journalist living near him in Santa Barbara, California, and he is working with Mexico’s Universidad Intercultural Maya de Quintana Roo to distribute it as a college text. He is in the Yucatan this month to give copies to leaders in the Maya community and to libraries in the area.

He will also be returning in November to lead a unique expedition being offered through the Santa Fe Workshops. Accompanying Everton will be David Sterling, founder and chef de cuisine of the Los Dos Cooking School in Mérida, Mexico, which is devoted exclusively to Yucatan cooking. Sterling is also the author of the cookbook Yucatán: Recipes from a Culinary Expedition, winner of the 2015 James Beard award. The ten-day culinary and photographic expedition aims to provide a ground-level view of the foods, landscape, and culture of region. Joining Everton and Sterling will be photographer Jennifer Davidson, who has been working in Latin America for many years.

For Everton, the two trips are opportunities to celebrate a place that has drawn him back over and over for more than 40 years. By any measure, his work there represents a monumental commitment. “The Yucatan has shaped my life,” he says.

Culture Shock

The disappearance of the Mayan race in the 9th century is not fully understood. “The so-called collapse took place over a period 400 years, and many of the explanations that have been put forward for why it happened really don’t hold up,” Everton told Pro Photo Daily in 2012. “But of course the bigger point is that the Maya really didn’t disappear.”

When he first traveled to the Yucatan as a teenager, Everton was already a veteran traveler, having just returned to the US after hitchhiking around the world.

“It was still possible then to go somewhere and shift centuries or even millenniums,” he said. “I was in the desert in Afghanistan once, watching a camel caravan, and I knew that somewhere overhead there were astronauts looking down at us. It was amazing. You heard the term ‘culture shock’ a lot then. Today, with KFC and McDonald’s everywhere around the globe, it’s harder to have that experience.”

Everton had taken pictures during his journey and thought about publishing them in a book, but instead he took a job with a company that made educational films. He was promptly sent to work on a project in the Yucatan, a place that did not seem particularly attractive when he first saw it.

“The landscape was flat, and of course you couldn’t see much from the jungle floor, other than jungle,” he says. But he found the people of the area to be warm and open, and he began thinking about telling their story with pictures.

At first, Everton considered creating a photo essay along the lines of W. Eugene Smith’s famous “Country Doctor” story in Life magazine. He soon gave up on the idea: There was simply too much story to tell, too much to explain about the lives of people like the chicleros, who bleed chicozapote trees for the natural substance used for making chewing gum.

Then he thought about telling the story of a season in the life of the modern Maya. “I thought it would make more sense to take a year, and do the story that way,” he said. “And the more I got into it, the more I understood how little I knew.”

Changing Story

In those early years, before his career as a travel photographer took off, he supported his Yucatan project with a number of part-time jobs, including working as a whitewater river guide in California and Oregon.

Five years later, after many trips to Mexico, he thought he had enough material for a book. Publishers, however, had a hard time grasping what he was doing. “At the time, the ‘Don Juan’ books by Carlos Castaneda were very popular, so they all wanted to know if I had a drug-taking shaman showing me around in the story,” Everton says.

Everton’s story changed over the years, as tourism developed in the Yucatan. His subjects changed as well. “When I first went down, the Maya had no concept of a Kodak moment,” Everton told Pro Photo Daily. “Nobody owned a camera, and people might have one or two pictures of them taken over the course of their lifetimes to commemorate events like a baptism or a visit to a sacred site. So when I came in with my camera saying, ‘I want to take pictures of you,’ it was completely outside of the realm of their culture.”

Everton told the Los Angeles Times that when he first went to the Yucatan, he was treated like “the village idiot”— tolerated and indulged — by the Mayan people: “I learned that asking people if I could photograph them often opened up unforeseen opportunities,” he said. “The hard part was overcoming my shyness. It forced me to interact with my subjects.”

His relationship with the Maya was cemented when he later showed them the pictures he’d taken. “Over the years my friends became increasingly sophisticated in their critical appreciation of photography and began to understand what I was doing,” he said in 2012. “They started to suggest photos. They would invite me to photograph not only ceremonies and special occasions, but also daily occurrences.”

It has taken Everton four decades to tell the story he wanted to tell, and along the way the story of the modern Maya became his own story. “The people I ended up working with—they let me into their lives, and I promised them I was going to document their lives, and I just took that to heart,” he says.