Photographer Profile - Ali Smith: "When I'm telling women's stories, I'm the happiest"

|

|

|

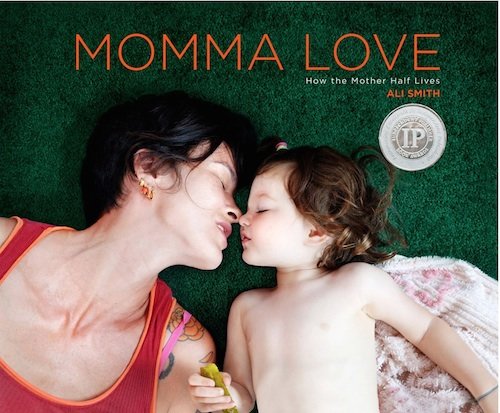

Her portraits and interviews with 40 mothers from a variety of backgrounds captured the everyday reality of mothering, from messy dinners to quiet moments of intimacy. Her subjects talked forthrightly about the self-questioning and feelings of isolation that come with motherhood, as well as its rapturous, bottomless love. A sentimental Hallmark card it was not.

“Momma Love is not only about the love a mother shows. It's about the love she is shown, by herself and the world around her,” notes Smith, who is the mother of a six-year-old.

The book turned out to be just the kind of Mother’s Day gift modern moms were waiting for and has become a perennial hit gift. “The essays are as detailed as the photographs that accompany them, and both will stick with you for a long time,” noted the New York Times. The Huffington Post praised the book’s honesty and beauty.

The response offered some redemption for Smith, who had worked on the personal project for more than a decade, in between commercial work and editorial assignments for publications including the New York Times, Marie Claire and Cosmopolitan. After a series of publishers turned down the book, she crowdfunded it through Kickstarter.

“We got a lot of praise from the publishers, but no one knew what to do with it,” she says. Sales teams couldn’t figure out how to market a book that featured an Oscar-nominated actress talking about being a mother in youth-obsessed Hollywood, an African American woman raising two adoptive sons of different races, and a mom determined to raise her two-year-old during her own battle with a terminal illness.

This year, Smith is adding to the love: For each copy of the book sold before May 8 at MommaLoveTheBook.com, she is donating $10 to Women In Need, an organization that provides shelter and other aid for homeless women and children in New York.

A native New Yorker, Smith picked up photography back in the days when she was the bassist for the rock band Speedball Baby. She documented the group’s tours but found her niche when she began photographing women. Her first book, Laws of the Bandit Queens, featured portraits of 35 celebrities — from comedian and actress Sandra Bernhard to singer and poet Exene Cervenka — who forged careers in uncommon ways.

“I realized early on in my photography that when I’m telling women’s stories, about things I’m inspired by, I’m the happiest,” says Smith.

For the past year, Smith has been working on another series about mothers and is now beginning to show the work. She calls it “a continuation” of what she was doing with Momma Love, though the subject of the project is far more somber: She has been photographing mothers who have lost children to gun violence.

7 Kids a Day

“It was the third anniversary of the Sandy Hook school shooting,” says Smith, recounting the day she began the project. “There was a gathering of people in Manhattan who wanted to commemorate it. I took my son, though I didn't tell him what it was about. I wanted to represent and not ignore the tragedy. I heard a woman speak about her own experience as a gun-violence victim. And I spoke with her afterwards.”

The woman was Kim Russell, a survivor of a robbery and gun attack that claimed the life of a friend. Russell had gone on to become National Director of Outreach for the group Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America, and through her Smith was introduced to women whose children had been killed by guns.

They included

Oxsana Naumkin of Saratoga Springs, New York (above), whose son Nicholas was 11 when he was accidentally shot in the head by a playmate just before Christmas in 2010, and Natasha Christopher (below),

whose son Akeal was shot in the head in a confrontation with teenagers in Brooklyn. He died on his 15th birthday.

There was also Diana Rodriguez (below), whose 18-year-old daughter Samantha was at

a bus stop in the Bronx when she was struck by two bullets during a gang-related shooting.

Hearing their stories, says Smith, “triggered fear in every part of

me.”

“I felt fear for my child and for other people’s children,” she says. “I thought about what it would be like as a mother whose child was killed that way."

The national conversation about gun violence has become stalled and rhetoric around the issue has hardened along political, social and geographic lines, says Smith. "I wanted to give faces to these killings we hear about," she says. She titled her project “7 Kids a Day,” because, she notes, that is the number of people under the age of 19 who are killed by guns on an average American day.

Crying That Doesn’t Stop

Gaining the trust of the mothers she photographed sometimes was difficult. “It’s understandably an insular community,” Smith says. “There are people who want to exploit their stories. They can also face personal attacks.”

Among the mothers Smith photographed was Nicole Hockley (below), whose son Dylan was one of the children killed by Adam Lanza at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, on December 14, 2012. Hockley described to Smith how her other son, Jake, had howled when he was told about his brother’s death. “She told me she’d never heard a child make that kind of noise before,” Smith says.

She also told Smith

that she had been the target of insults and allegations springing from a conspiracy theory involving the Sandy Hook shootings. Adherents to it claim that a number of mass killings in recent years were hoaxes perpetrated by the government in order

to further gun-control laws.

Smith’s encounters with the women left her emotionally drained. “I sat with them and cried with them for hours, and I would leave feeling totally depleted,” she says. “But then thought, ‘They never stop crying.’”

"I don't know how she does it, but Ali manages to capture what it feels like to lose a loved one to gun violence,” says Kim Russell, who now works with the Brady Campaign To Prevent Gun Violence. “There is unbearable, unending grief but also strength and courage. It's heartbreaking but important for Americans to witness that pain, the aftermath — to understand violent loss, to know they don't want to wear those shoes. These stories and photographs of survivors will ultimately be what sets our country back on a path to sanity when it comes to guns.”

Smith says she was as non-invasive as possible when she made the portraits. “I’m just a woman with a camera,” says.”In my portraiture, I like to strike a balance between contrived moments and telling documentary style. I would take the lead of the mothers, and if I saw some nice light or a good location, I’d try to use it.”

Her connection to the women has grown over time. “There’s good and bad to that, because it’s very hard to turn off that knowledge once you have it,” she says. “Once you can count among your friends women who have lost children to gun violence, you’re not the same.”