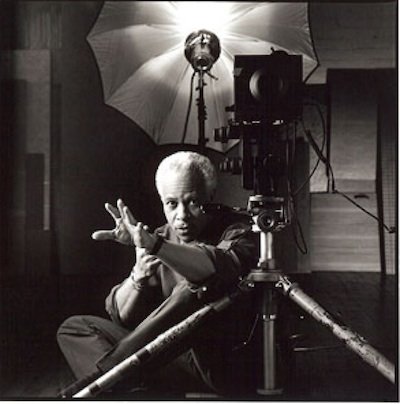

Photographer Profile - Lou Jones: "I don't actually call them poems"

|

|

|

Since then, he has become photography’s most prolific bard.

For years, Jones has been sending out short missives written in verse to friends, editors and advertising clients. His notes are about everything and anything, from his travels to the act of creativity. This one, for instance, was written just this April, during a trip to Japan:

bubbles

parts of this country are effervescent

carbonated

bubbles

written in kanji

ive been photographing for decades with an eye the differences

parts are indecipherable

opaque

but

in helvetica

all the rest is out of sight

or just out of focus

Another one, written in May of 1997, contemplates one of photography’s essential ingredients, light:

photojustice

tear a hole in the firmament

figure how to ride the light

energy

those indifferent to the moon

where the skies end

the photography begins

smell of rain & thunder

with my

camera

i can purchase the sun

i cant be held responsible

though sunlight can be cruel

“I don’t actually call them poems,” Jones says. “People who write poetry are attacking a sophisticated art form, and I don’t think anything I’ve written rises to that level. I call what I write prose-poems.”

Jones began writing them early in his photo career. “I just thought I had no chance of succeeding, but I started finding clients and traveling,” he says. “I’d go to Romania or France. And I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful if I could let my friends and potential clients know that I’m doing this?’ So I started writing these things on postcards and sending them to people. I would mention photography only in passing — maybe just the job I was working on. I never asked for work.”

The writing, Jones says, helped discipline him in the art of self-promotion. “The exercise forced me to keep in touch with people who’d given me work, “ he says.

Eventually, he became known for his postcards. “I’d go to see a client, and I’d see one of them on his or her bulletin board. And sometimes if I didn’t send one to someone for a while, they would ask me if they’d fallen off my mailing list,” he says.

No doubt other photographers have dashed off lyrical lines from time to time. But Jones is probably unique in his systematic use of poetry as part of a business plan. His long career — he’s shot for IBM, Federal Express and Nike as well as National Geographic, People and other magazines — might in part be attributable to his verbal as well as his visual talent.

There’s a marketing lesson to be gleaned from Jones’s experience: Consistency counts. So does honesty. His poems are an genuine reflection of how he’s experienced the world, rendered in his own style — no capitalization — one line at a time.

In and Out of the Sandbox

“Sometimes they come quickly and sometimes it takes longer,” he says of his prose-poems. “I have to look up spellings and word definitions, so they can take a couple of hours. Each one is unique. Each person I send them to gets an individual idea.”

For instance, this one, written to a client from Las Vegas in 2012:

neon

here sunset falls faster than

neon lights are manmade substitute for sun

most opulent most decadent shoulder to

shoulder with most despicable

eyes notice everything across gaming tables

roulette

blackjack

craps

sin

erase the

family fortune without leaving the airport

money

buys anything

everything

kitsch

flesh

all you can eat

buffets

money

Jones credits a college roommate with introducing him to both poetry and photography. The college was Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, where Jones studied physics. “Photography was a hobby, he says. “My roommate told me about f/stops, shutters speeds, and I taught myself everything else.”

That part, he says, was fairly easy.

After college he worked as a physicist for a few years, which is not the usual route to a career in photography. As it turned out, he didn’t enjoy the job.

“I found that I didn’t play with others well in the sandbox; I was taking orders from people who I thought lacked leadership qualities. Let’s just put it that way,” he says. Photography beckoned.

Along the way, his career shooting for commercial clients has taken a few detours. In the 1980s he was hired by a group that organized trips for congressional delegations. Jones photographed congressmen in Central America and, through that job, ended up documenting the bloody conflicts in the region. He was also hired by a magazine to cover the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, a job he loved. “After that, I started seeking out clients who would send me to the Olympics,” he says. He’s covered 12 consecutive Olympics, summer and winter, and will be in Rio de Janeiro this summer to photograph the 2016 games.

What may have been his most memorable personal project came about, he says, after

an informal meeting with his studio staff in the late 1980s. “The business was humming along — I was shooting computers and high tech and all kinds of annual reports,” Jones says.

“When I started out, I was a nobody, a schmuck, and then we built something. But as I sat there with my staff, I said, ‘Is this all there is?’ I got into photography to illuminate

the world and make a difference, and here I was shooting annual reports.”

Not long afterward, he saw the BBC documentary Fourteen Days in May on television. The film, which tells the story of the final days before the execution of a prisoner convicted of rape and murder in Mississippi, proved to be an inspiration.

Words and Pictures

“It took us two years to get into the first prison, and it took six years to complete the work,” Jones says of his 1997 book Final Exposure: Portraits from Death Row. His portraits of 27 death-row inmates in prisons across America, accompanied by interviews, humanized the condemned and raised questions about the morality of the death penalty.

Among Jones’s other varied projects is the series "Sojourner's Daughters,” portraits of 26 women in the Boston area who made significant contributions to the African America community. He’s currently working on what he calls his panAfrica Project, aimed at portraying African countries in a way that is “devoid of the preconceived, western notions of distress: conflict, pestilence and poverty.” He has completed work in Egypt, Ghana, Lesotho, Senegal, Swaziland and Tanzania and recently launched a Kickstarter campaign to finance further trips.

Jones still sounds surprised about the turns his life has taken and where it has led him — from studying physics to shooting for companies like IBM and Aetna, from making portraits of death row inmates to documenting modern Africa.

“Going into photography may have been the stupidest decision I ever made, but here I am, 40 years later, and still at it,” he says .

He’s left not only with pictures, but decades worth of words. “People have told me I should collect the poems in a book, matched with my photographs, and we’ve been looking into that,” he says. It may include this one, written in 2012:

we are

borne of water

from it we gain meter & measure

vastness prepares us for the immense

journey ahead & the

search for fire

fire aspires to electricity

electricity is of invention

invention

begotten by learning

& passion

the flames never subside

maybe over the time smolders

but the

intellect is of air

& lofty ideas like ships before the wind

we can meddle with our knowledge & experiences

until in the end we are framed

deep inside the earth