Photographer Profile - Ernesto Bazan: "If you are generous, things come back to you"

|

|

|

Being forced by the Cuban government to leave the island in 2006 turned out to be a blessing in disguise, he says. “I lived there for 14 years and I loved being in Cuba and photographing there, so it was a big blow,” he says. “But it turned out to be a beautiful story.”

Bazan resides in New York now, along with his wife, Sissy, and twin sons Pietro and Stefano, after having lived in Mexico for a number of years. “My kids came up to me one day and said, ‘Dad, we would like to go to high school in the United States. That was in 2014. Now they are citizens of the world, like me,” he says.

It was Cuba — its people and its landscapes — that inspired Bazan’s best known work to date, a hauntingly beautiful trilogy of self-published books. David Gonzalez of the New York Times described Bazan’s photographs of the island as “remnants of a tropical dream — suffused with tenderness, color and a hint of mystery.” The books, Bazan: Cuba, Al Campo, and Isla, have become collector’s items.

Bazan says it was destiny that him to Cuba in 1992. Destiny is another word he uses often.

“I would like to tell you it was just by chance, but I truly believe it was something more than that,” he says. “I went there just out of curiosity — but Cuba ended up changing my life in so many ways.”

It was where he met his wife, where his sons were born, and where he found a consuming photographic subject. But whenever he wanted to take his family out of the country, he had to ask for permission. That grew irritating, he says. And when the government denied him permission to teach the popular workshop series he had launched — he was said to be teaching journalism without authorization — he and his family departed.

Now, with the recent normalization of relations between the US and Cuba, there is a possibility that he may be able to return to the place he captured so memorably. Or not. “I don’t know,” Bazan says. “There are rumors that I might be able to go back, but I haven’t tried yet.”

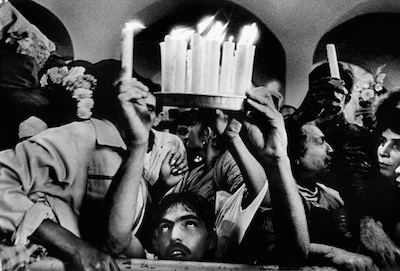

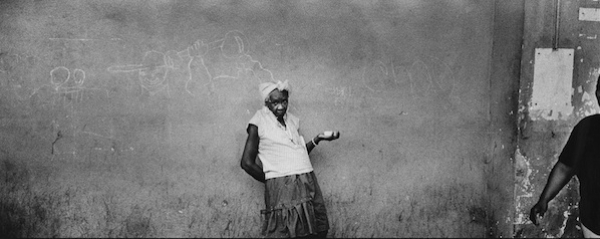

Meanwhile, he continues to lead workshops in Latin America and other places — he recently left to do one in Sicily, where he was born, and another in Naples, a city he adores. He is also working on a long-term photo project about Mexico, Peru and Brazil’s Bahia state, which Bazan refers to as his “new Cuba.”

Latin American Cantos

Bazan arrived in Cuba in 1992, after the country’s economy, no longer supported by the Soviet Union, had collapsed. His early pictures captured the lives of Cuban trying to survive the crippling hardships of the so-called Special Period. In 1998, his work earned him the W. Eugene Smith Grant for Humanistic Photography, and in 2000 he was awarded a Guggenheim grant.

The final book in his trilogy, Isla, was a contemplative reflection on the landscape and people of the island, captured in black-and-white panoramas.

For now, his destiny lies elsewhere. Three years ago, after photographing in various areas of Latin America — especially Mexico’s Oaxaca state, the Sacred Valley of Peru, and Bahia — Bazan had an idea. He decided to create a new book trilogy called Latin American Cantos.

“When I was young, my mother was always talking to me about Dante’s Divine Comedy, and that is what set me to thinking about my work in Latin America,” he says. "I realized that Dante used the poetic form called cantos, and if you look at the cantos as he drew them on a beautiful map, they were circular. This is what I have been doing — going in circles. I keep returning over and over to the same locations. People ask me why, and the only answer I can come up with is that by returning to these places, I am able to at least try to probe deeper and deeper into the subjects.”

Like his Cuban trilogy, the new books will be self-published, with creative, and sometime financial help from friends and students who have attended his workshops.

Bazan is not the kind of person who overlooks the idea of gratitude. In recent

years he has been self-publishing a series of books featuring photography by his workshop students.

He has also established a scholarship program to aid students who can’t afford the workshops. “It’s work because I have to do the fundraising. I also donate limited editions of my books to raise additional funds,” he says. The two most recent scholarship winners are Mexican photographer Yael Martinez, who is working on a project about drug-cartel violence, and Tammy Merino, a photographer from Chile who is working on a series about communities in Bahia that were founded by runaway slaves.

“How the scholarships got started is a beautiful story,” Bazan says. “A very good young photographer from Spain named Raphael contacted me to ask how much it would cost to attend my workshop in Sicily. I told him, and he said, ‘I’m sorry Ernesto, but I can’t afford that. I will save money and come next year.’ Something inside of me said, ‘Give this guy a break.’ I consulted with my wife, and she also said, ‘Give this guy a break.’ So I did. And at the workshop, the other students were so impressed by his work that they started saying, ‘Oh wow, we should buy Raphael’s pictures, we should get him a show.’ Then another student said, ‘Ernesto, why don’t we create a scholarship fund, so that Raphael can come for free next year?’”

There was only one possible response, says Bazan: “I said, ‘Yes, yes, that’s a beautiful idea.’”

Generosity is Destiny

There seems to be a spiritual context to most of what Bazan does, at least as he explains it. He says he realized what he wanted to do with his life after having a dream at age 17, in which a voice told him to become a photographer.

“What I find most amazing is not that I had the dream, but that the next morning I remembered the dream and followed through with it. I told my parents that I was going to become a photographer. Of course my parents thought I was completely insane. My father was a surgeon and thought I would follow in his footsteps.”

Bazan applied to several schools in the US and in 1979 began his photographic education at the School of Visual Arts in New York.

The first time he went to Cuba he took along a friend, one of his SVA instructors. “He was my printing teacher, and after I graduated he was my printer. I was applying for a grant at the time, and I asked him for a favor — to make prints for the application. I had this trip to Cuba planned, and I told him that if I got the grant, I would take him to Cuba with me,” Bazan says.

It was the friend who spotted a group of girls in Havana and urged Bazan to talk to them. One of the girls would become his wife. “I was taking pictures, and he yelled, ‘Ernesto, come here, they are beautiful!’ So I like to say that my little act of generosity of taking my friend to Cuba paid off big time,” Bazan says.

For Bazan, generosity is destiny, and it’s beautiful.

“It goes back to something I believe that is important about life,” he says. “If you are generous and altruistic with other people and care for other people with no other intention than just wanting to help them, things come back to you in a big way.”