Photographer Profile - Jaime Permuth: "As an artist, you're always fighting. Everything has to come from you."

|

|

|

Following the normalization of relations between Cuba and the US, photographers have flocked to the island nation, hoping, perhaps, to document it before political, cultural and economic developments change its character. The growing number of photographic workshops scheduled to take place in Cuba this year is an indication of how popular a destination it has become for professionals and enthusiasts alike.

“Cuba is on everybody’s mind right now,” says New York-based photographer Jaime Permuth. In March, Permuth, who is on the faculty of the Masters in Digital Photography program at the School of Visual Arts, will be leading a workshop in Cuba along with Katrin Eismann, the chairman of the department. As of mid-January there was a waiting list of applicants.

This will be Permuth’s second visit to Cuba; he was there in late 2014, when La Fototeca de Cuba in Havana invited him to present his monograph Yonkeros at the annual Month of Photography festival. The week after he returned to the US, President Obama announced the historic shift in relations between the two countries.

The photographs Permuth shot while he was in Cuba capture the romance and color of Havana, but there is also a sense of questioning in them that might reflect his own past.

Permuth grew up in Guatemala during the civil war there, in what he describes as a “very right-wing climate” that shaded his impressions of Cuba. “Anytime anyone said the word ‘communist,’ they said it with a sneer. People greatly feared Cuba and were very sarcastic about the efforts of the Cuban system,” he says. “So I had to overcome a lot prejudice accumulated over my childhood when I finally went to Cuba to connect with whatever was there. It was a very interesting destination for me.”

Once in Havana, Permuth walked everywhere. “I went miles and miles every day, which is the best way to explore another country’s reality,” he says. He was struck by the city’s vibrancy — the mid-20th century Chevrolets and Russian Ladas on Calle Neptuno and buildings that he describes as “majestic and dilapidated at the same time” — as well as the suffering people endured during more than 50 years of communist rule and US trade restrictions.

But, he notes, the Cubans also had a strong sense of identity — a notion of belonging to a place — that affected him deeply. As a Guatemalan living in the US, Pemuth wrote later, he became “painfully aware of how uprooted and unmoored I’ve become from my childhood sense of self. There is no specific place on earth which I can lay claim to. I belong nowhere in particular. ”

Communities On the Margin

Permuth’s photography, including series that are documentary in nature, is filled with a sense of self-exploration. His work has been seen at the Museum of Modern Art, the Queens Museum of Art, the Bronx Museum of the Arts, the Museum of the City of New York, the Jewish Museum, El Museo del Barrio, and the Brooklyn Museum of Art. He was a 2014 Smithsonian Museum Artist Fellow and a winner of the Latin American Fotografía competition.

He came to photography through his family: His grandmother, who immigrated to Guatemala from Switzerland in the 1920s, was a talented and, he says, obsessive amateur photographer, as was his father. “When I was old enough to want to learn photography, my dad taught me. But most of my learning happened by looking at the great photographers,” he says. “We had a fairly good photography library in our house. So I was able to study with Koudelka, and Capa and others.”

He went on to study in Israel for five years, and it was then that he decided to become a professional photographer, “as opposed,” he says, “to a lawyer or a psychologist or other profession that my family expected of me.” He moved to New York, received a masters degree from SVA, and launched his career. A decade later he was back at the school earning a second masters in digital photography, after which he was hired as a faculty member.

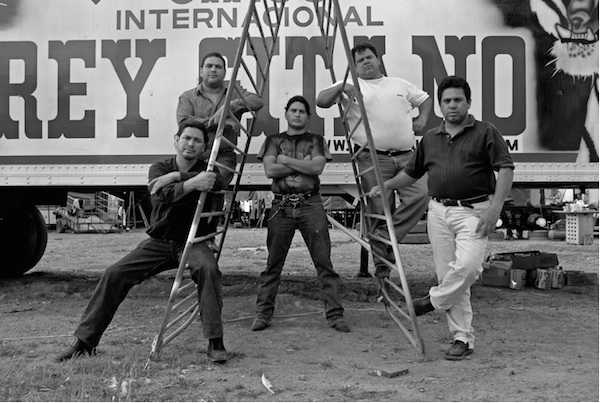

Among his notable projects are “Tarzan Lopez,” about Guatemala’s largest family-owned circus. His best-known series is “Yonkeros,” which was published as book in 2013 by Fabrica Editorial (Madrid). Permuth’s photographs focused on the immigrant mechanics working in the junkyards of the Willets Point area of Queens, New York. The yonkeros — the term comes from the English word “junk” — strip cars and sell the metal and parts. Permuth launched the project in 2012, just as the city began debating redevelopment plans for Willets Point.

“The work is about how the Latin American mechanics there tried to go from being immigrants to being mainstream,” Permuth says. “It’s a story of them making good, but also about a city that increasingly has no place for a community like this.”

He says it is just such communities that he is drawn to. “The yonkeros are people who play by their own rules and exist on the margins of society. I like that kind of scenario,” he says. “It’s very romantic to me — people who are playing against the odds and may not succeed, ultimately, but they stick by their own particular way of living. I found that in Willets Point and with the circus in Guatemala. It’s one of the themes that shows up in my work.”

His attraction to such communities, he says, may derive from his identity as an artist.

“It’s certainly the harder road,” he says. “As an artist, you’re always fighting, You can never let your guard down — everything has to come from you. It’s your motivation, it’s your will that makes something happen, it’s your vision. It’s a rebellious stance, given that there is very little support for artists in society.”

Interior and Exterior Worlds

Permuth divides his time between Guatemala and New York, but spends summers in South Korea. “My wife is Korean, and I’ve been doing a fair amount of work there,” he says. He recently returned from Beijing and is working on a new project connected to the trip.

Another project, related to the work he did as a Smithsonian Fellow, is a departure for Permuth. “It’s a meditation on how the urban street changes in war and peace,” he says. “It’s an archive project — none of the photographs I am using are mine; some of them are from the early 20th century. It’s a challenge. My artistic process in this case is transforming the source images, aesthetically, and then laying them out sequentially in book format to try to talk about the things that interest me.”

He has also been working with Fototazo, a non-profit online platform that combines social giving and photography through micro-grants to photographers in Latin America. He and the site’s founder, photographer Tom Griggs, have collaborated on a series of what they call “Notebooks” featuring interviews with photographers from different Latin American countries.

“I believe in Latin American photography in general — networking and avenues of communication have opened up for photographers there,” Permuth says. “But on the other hand, I think the sense of place is not as evident in photography from Latin America — or any place — as it used to be.”

Today’s artists, he says, have in a sense also become estranged from the worlds they live in.

“The outer world has receded and the interior world has come forth,” he says. “I’m not even sure you can make generalizations anymore about what is Latin American about Latin American photography. But if there is a difference, I think photography from Latin America is not cold — it’s less dry and academic than in the US and Europe. There is still something very personal about each person’s project.”