Photographer Profile - Hannah Kozak: "Having the camera gave me protection and connection simultaneously"

|

|

|

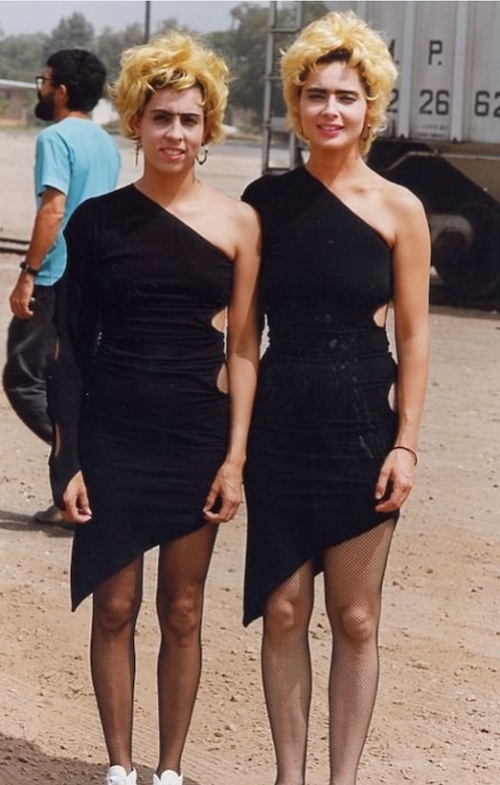

Kozak is a member of an exclusive club of photographers who at one time did movie stunts. In fact, she may be the only member of that club. She began her career as stuntwoman when she was 24, working on the 1985 film Year of the Dragon. “They flew me from California to New York in the middle of the winter, and I had to run out into a street in high heels and a miniskirt and bounce off cars,” she says. “That was my introduction to stunt work.”

Kozak says that as a child she was fearful, which may make her later choice of jobs seem counterintuitive. But it was a purposeful choice. “When I was about 10, I couldn’t go into the ocean without someone holding my hand. I remember making the conscious decision that I didn’t want to be scared, and I think that’s what got me interested in doing stunts.” Kozak says. “I didn’t even know what a stuntwoman did. I just knew you couldn’t be scared.”

Over the years, Kozak appeared in movies and television shows, including Con Air, Transformers, Iron Man, and Twin Peaks, doubling for actresses like Isabella Rossellini, Cher and Angelina Jolie. It was while working on a film in 2004 that she broke her feet, and after which that she reassessed her life. “As I got older, and it took longer to heal from injuries,” she says.

She decided to walk away from her stunt career, then ended up getting into a line of work that scared her in a different way.

Kozak doubling for Isabella Rossellini

Kozak doubling for Isabella Rossellini

Kozak went back to college to study psychology. As part of her course work, she began to confront a source of pain that had troubled her

since childhood by renewing a relationship with her estranged mother. And whenever they met, Kozak had a camera with her.

“Having the camera gave me protection and connection simultaneously,” Kozak says. “By the time I graduated in 2008, I had started making strides in healing my relationship with my mother. And that’s when I started photographing her earnestly. It’s six years later, and I’m just starting to feel that my work is becoming complete.”

One Punch Too Many

Kozak was a nine-year-old growing up in California when her mother left her and her father.

“She had fallen in love with another man,” Kozak says. “She would come to pick me up on weekends. I didn’t know until later that it was because she was afraid to be alone.”

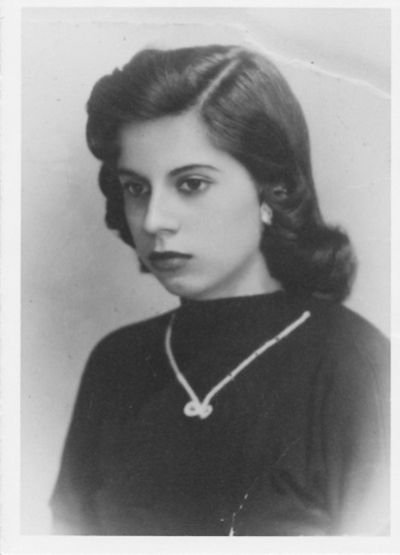

The man her mother had gone away with turned out to be violent. When Kozak was 14, her mother ended up in the intensive-care unit of the UCLA Medical Center. “He had gone too far,” Kozak says. “My mother had such severe brain damage that she had eventually had to be put in an assisted-care facility for the elderly.” She was just 42 at the time and has been living in various care facilities every since.

“Every time I talk about it, I think I’m not going to cry. It’s the kind of wound that heals over, but there’s scar tissue,” says Kozak. “I hated going to see her at that place — it made me depressed. And then if I didn’t go, I felt guilty. So at some point I just pulled out, and that worked for a while.”

Above and

Below: From "He Threw the Last Punch Too Hard"

Above and

Below: From "He Threw the Last Punch Too Hard"

Kozak, whose father was a survivor of Nazi concentration camps, spent some time in Israel. When she returned to

California, she got a job in a camera store. She had been an avid photographer since picking up her father’s Brownie when she was 10 and was happy to offer customers tips about gear. One day,

the stunt coordinator the 1980s-era TV show The Fall Guy walked in. “I begged him to bring me to the set, and I said I’d take some pictures for him,” Kozak says. That led to

her work in films.

Since her stunt career ended, Kozak’s photography has consumed her. The various fine-art projects she has taken on suggest her willingness — perhaps a better word would be desire, or need — to confront darkness. An example of that is her series “Pain and Loneliness,” a collection of nude self-portraits begun after a failed marriage.

“The irony with those photos is that I’m actually an extremely private person — I keep to myself,” she says. “I always equated vulnerability with weakness. I was always a tough girl. But I learned that it’s actually the opposite — it takes strength to let yourself be vulnerable. Those photos are me being very vulnerable.” In 2014, the work earned Kozak the Female Photographer of the Year prize in Julia Margaret Cameron Award contest. Among her other projects is a multimedia series about her father’s life in Poland and his imprisonment in the forced-labor camps.

But it is her project about her mother that has haunted her more than any other. “I would come home from the facility she’s living in and edit my photos and be in tears,” she says. “I have to throw myself into it; there’s no other way to do it. It hasn’t been easy watching her life. I can’t imagine what it was like for her to live it. I’ve got to tell her story. If I don’t tell it, it won’t get told.”

The Storyteller Within

The camera, says Kozak, allowed her to see her mother in a way she couldn’t as a child. She was no longer merely a participant in the events of her mother’s life, but an active observer constructing her own narrative.

“I’m a storyteller and I didn’t know I was,” she says. “At some point I realized I could tell this story.”

She began to assemble dummy photography books. Then in 2011 photographer Aline Smithson, founder of the popular website Lenscratch, featured the series, which Kozak had titled “He threw the last punch too hard.”

“Hannah keeps her camera focused on subjects that are once difficult, poignant, and personally challenging,” says Smithson. “I have followed her journey as she used her camera initially as a psychological shield. The camera then transformed her into a witness and later into a documentarian, allowing her to shift her intention from hurt to love.”

From "Pain and Loneliness"

From "Pain and Loneliness"

Together, they began laying out a book, which, in 2014, was shortlisted for the CDS Honickman First Book Prize in Photography, the prestigious award from the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University.

“Ever since I was a little girl, I have preferred the truth to clever fictions,” Kozak stated in her proposal. Going further, she wrote, “I have early fond memories of my mother as a beautiful, passionate, and vivacious Guatemalan Sophia Loren. But after she left us, I judged her as an impetuous, selfish, reckless, and negligent mother. I had tremendous feelings of abandonment and rage toward her. I carried so much anger. Yet whenever I saw her, I was overcome with pity and sadness. Seeing her gnarled hand was more than I could bear. I virtually ignored my mother in an attempt to distance myself from my own pain. I think we become accustomed to looking away. But we can’t grow much forgiveness and compassion that way.”

Photography, noted Kozak, was the catalyst for her healing. Her black-and-white portraits capture the shades of gray in the truth she prefers. “Her spirit, her will to live, is a great testament to her ability to live without bitterness,” wrote Kozak of her mother. “This is our personal quest: to find out who we are, why we are here, and what lies in store for us.”