Photographer Profile - Benjamin Lowy: "I was thinking about how everyone is a photographer now"

|

|

|

As Lowy tells it, he was out walking his dog in New York City when he realized how the iPhone could change his life as a photographer. This was back in 2008, shortly after Steve Jobs had sprung his smartphone on an unsuspecting world, and two years before Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger launched Instagram. On his walk, Lowy realized he no longer needed to carry a camera wherever he went. “I had one in my pocket already,” he says.

Lowy went on to champion mobile photography while working as a photojournalist covering the wars in the Middle East. In 2011, the New York Times Magazine published his series “During War Time,” photographs of daily life in Afghanistan made with the Hipstamatic app.

At the time, many photographers considered the iPhone to be the antithesis of craft and creativity, despite its growing popularity. A tipping point in its acceptance came in 2012, when Time magazine assigned Lowy and a number of other photographers to document the effects of Hurricane Sandy via Instagram, only hours after the storm hit. One of Lowy's images was used on the cover of the magazine as well. "It got a lot of attention," Lowy says.

A year later, Lowy was once again walking along the streets of New York when he had another revelation—this one about how profoundly the mobile-photography revolution he helped pioneer had changed the medium.

“I was thinking about how everyone is now a photographer, how there are cameras everywhere—smartphone cameras, government surveillance cameras—and I began wondering, ‘How can I go backward? How can I get rid of everything being documented?’” he says.

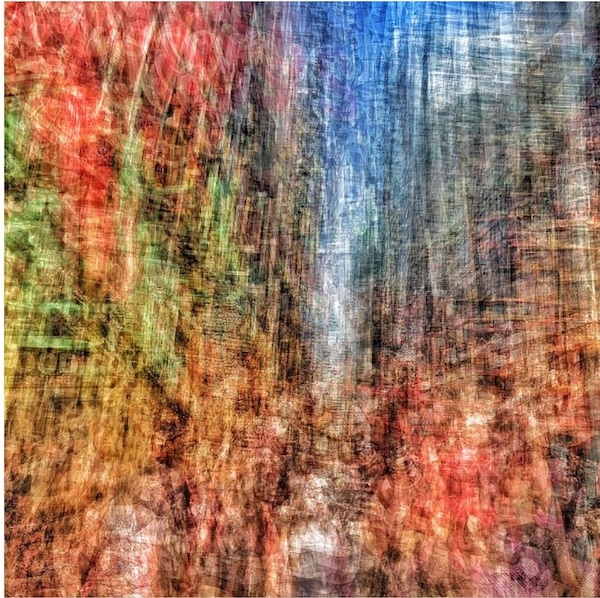

The result is his fine-art series “Walkscapes”— smashing mash-ups of color and light that render everyday reality as a heightened visual experience.

“Here’s what Sydney would look like if Impressionists had painted it,” noted BuzzFeed Australia, describing the “Walkscapes” work Lowy created there. The same could be said of images for the series made in New York, Chicago, and other cities.

The project turns the idea of 24/7 photography inside out. “I wanted to create something that is a single image but is made up of many images,” Lowy says. To do that, he hacked an app meant for time-lapse photography, using it to shoot at selected intervals as he traversed a city block or some other set distance. “The app wasn’t intended to do what I do with it, but I figured out a way to make it work,” Lowy says. “The app then lays all the images together and I do some cropping, sharpening and toning.”

He’s never quite sure what he’ll get. But he likes surprises.

“The digital world is so precise that there is no chance left to the photo gods. So I’m always trying to create space for that moment,” Lowy told National Geographic’s Proof blog last year.

A Failed Illustrator

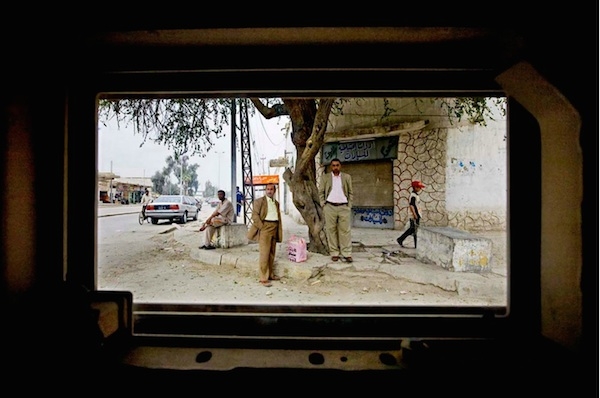

The “Walkscapes” series marks the evolution of a celebrated photojournalist who covered the war in Iraq at a time when, Lowy notes at his website, walking the streets of Baghdad “was tantamount to suicide.” In 2011, he won the Duke University Center for Documentary Studies/Honickman First Book Prize in Photography for his book Iraq/Perspectives, which featured photos shot through Humvee portals; the images captured the ravaged landscape of Iraq from the point of view of a US soldier. In 2012, Lowy won the International Center of Photography Infinity Award for Photojournalism, capping his achievements.

But it all happened more or less by accident. What he wanted to be, back when he was studying Italian Renaissance painting at Washington University in St. Louis, was a comic book artist. The problem, he says, was that his illustrations lacked the dynamism and sense of movement that comic book artists know how to imply.

Perhaps that’s because he learned to draw human anatomy by making studies of cadavers in the morgue of the university’s medical school. “My drawings were pretty stiff, excuse the pun,” he says.

He also made tracings of nude figures he found in oversized art books by photographers like Herb Ritts and Howard Schatz. One day he found another big volume on the shelf at his local bookstore—Inferno, by a photographer he’d never heard of, James Nachtwey.

“I assumed it was another fashion book,” says Lowy. Instead, he discovered Nachtwey’s black-and-white journey through 10 years of hell in places like Romania, Chechnya, Kosovo and Rwanda. “I sat in the bookstore reading that book for hours. And it changed my life. It took me in a different direction,” Lowy says.

Though he eventually earned a BFA in fine-art photography from Washington University, as a photojournalist Lowy was self-taught. “I took a leave from school and moved to Paris, where I had a girlfriend—I figured that if I was going to be a photographer, that was the place to do it,” he says. There, he met a photo editor for Newsweek magazine’s French edition, who lined him up with an assignment to cover the Second Intifada.

“There was a new agency and they needed a photographer on the West Bank who could speak both Arabic and Hebrew,” says Lowy. “I said, ‘Yeah, sure, I speak Arabic and Hebrew,’ though I couldn’t. I went there with 400 rolls of chrome and didn’t know a thing about what I was doing. I bought my camera when I got to Jerusalem—a Nikon F3. I still have it.”

A Cure for Burnout

Lowy is circumspect in describing exactly how he creates his “Walkscape” images—he doesn’t reveal what app he uses or details about how he finishes the work—because he’s seen some copycat work. “I want to try to get the work into galleries, so I’ve become a little protective of it,” he says. The series has been featured in a few exhibitions, with prints as large as 60 x 60 inches. “We can make them that big because there’s so much digital information in the images—each one is made up of as many as 130 iPhone photographs,” he says.

If the new work reflects Lowy’s earlier interest in illustration and fine art, it also speaks to his desire to walk away from conflict photography, to build a different kind of career so that he can spend more time at home with his young children. “I was entering this place where I was trying to see what else I could do,” he says. At the National Geographic blog, Lowy noted that creating “Walkscapes“ was one of the most fun things he’s done in a long while.

“I really enjoy making them,” he said. “Let’s say I’m on my way to assignment or I’m picking my kids up from school, I just put myself in this mindset where I’m like, ‘Okay, I’m not doing my street photography stuff now. I want to feed another part of my soul.’ It’s more about my journey down the street. For the first time, I’m not really aware of everything else around me.”

Ultimately, the work demonstrates Lowy's abiding desire to try something new, as he did when he set out for Paris to become a photojournalist, and as he did when he began using an iPhone. Now that Instagram has become part of the daily fabric of people’s lives, even mobile photography can begin to feel like a job, Lowy notes.

“You can get to the point where you feel like you have to take pictures every day for your audience,” he says. “If you push yourself to do something every single day, you’re going burn out.”