Photographer Profile - Larry Fink: "I've always thought of myself as an outsider"

|

|

|

The award will be presented on April 30, at the ICP’s annual gala at Pier 60 in New York City’s Chelsea Piers, a swank affair not unlike the society balls Fink famously photographed in the 1970s. Those images of Park Avenue soirees, paired with photographs he made of his rural Pennsylvania neighbors in the seminal book Social Graces, left a lasting impression on the photographic community, notes Fink’s ICP citation. Fink has published other books, too, about subjects ranging from beatniks and boxers to bugs. He’s had solo exhibitions at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Whitney Museum of American Art, among other venues, has been awarded two John Simon Guggenheim Fellowships and two National Endowment for the Arts grants, and has created acclaimed editorial work for magazines like Vanity Fair and the New Yorker. He’s also been teaching for more than 52 years, at Yale University, Bard College and other schools.

And yet, Fink says, he has never really felt like a member in good standing of the fine-art community, which is why he didn’t expect to be honored by the ICP. “I was asked to submit some work, which I did, and then just assumed nothing would happen,” he said in a recent interview.

“Why did you think that?” he was asked

“I’ve always thought of myself— even though I’m a friendly guy—as an outside player,” he said. “I just kind of consider myself on the outskirts of the art scene.”

“Why?”

“Because of my character.”

“What aspect of your character would make you an outsider at ICP?”

“Well, it would make me an outsider at any institution,” he said.

Sensual Empathy

In conversation, Fink unfolds thoughts as he goes along, searching for the right words to describe an idea and then letting the words guide him to other ideas. Money, he says, “is the greatest spiritual dis-enfranchiser there is. However, I’ve been able to earn some of it.” He describes his mother, a powerful figure in his life, as a “high-stepping elegant bourgeois gal and a very combative confrontational socialist.” He also notes that besides being a dedicated Marxist who inculcated in him her leftist ideals, she was a “Minkist” who loved fur coats. “And because of that, the trappings of elegance have always had a deep visual appeal to me,” he says. His sense of politics also formed his outlook about a what a life in photography could or should be.

“I’m as ambitious as anybody ever has been, but I never really thought of photography as a career,” he says. “I was really trained—or ‘illusioned’—within the construct of the socialist revolution and its transformative powers. So I came to photography from that position, which was outside the center of the way the culture worked. And it was there that I got my outsider bearing, if you will.”

That bearing, along with a deep sense of humanity, informs his photographs, says ICP curator Kristen Lubben, who was on the 2015 ICP Infinity Award Selection Committee. “For decades, Larry has been an astute observer of social interactions,” she says. “He is attuned to potent physical gestures and subtle emotional signals. His photographs invite us to linger and contemplate the tensions both between and within his subjects.”

Fink has recently been archiving his lifetime's worth of images for a retrospective book to be published by the University of Texas Press. “You look at a print and you put it in your hand and it touches you back with the memory of that time,” he says of the job. Asked to select a handful of photographs that epitomize his work, he demurs. “I’ve made a lot of f**king good pictures since I started,” he says.

He started as a teenager growing up in West Hempstead, Long Island, using cameras his father owned. But where he first formed a notion about what it might mean to be a photographer was, he says, at Stockridge School, a progressive boarding school in Stockridge, Massachusetts, that has since closed. Fink was sent there because of trouble he had been getting into at home. “Real serious trouble—I was stealing cars,” he says. “Stockridge turned me into a community citizen, which was what I wanted to be anyhow.” At Stockridge, he says, his interest in photography “blossomed into an object of identification.”

After that he went to Coe College in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, for exactly a month and a half. Then it was back to Manhattan. Living in Greenwich Village, he began hanging around with what he later termed “second-generation” beatniks who “were more crazed, more depressed, more engaged with their sense within quasi-history.” In 1958, when he was 18, he photographed his subterranean companions on a cross-country trip; those images were finally collected in the 2014 book The Beats.

Fink’s formal study of photography at this point amounted to a couple of courses at the New School in New York, but more important, he says, were his private sessions with photographer Lisette Model. “We had seances,” he says. “I got my humanity from Lisette, and the eccentricity—or I should say the license to have eccentricities.”

His professional career began when he got a job with the old Three Lions photo agency, which had a group of accounts servicing lay Catholic publications. “My experience shooting for them was profound,” Fink says. “Here I was, a leftist and Jewish—the ultimate outsider.” But that was also when he found how an outsider with a camera could wrap himself around other people’s lives, climb inside their skins and come to understand them. He calls this process “sensual empathy.”

“It’s the idea of the transformative merger between you and the person you are seeing, that you somehow try to enter their form, their skin, their mass, their muscle, and potentially, possibly, their soul,” he says.

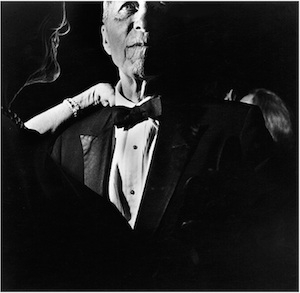

Social Graces

Fink’s ideas about photography and his ability to wrap himself around other people’s lives came together one evening in 1968, when the Metropolitan Museum of Art held a gala to celebrate its centennial. Fink was hired to take pictures of the beau monde in attendance, and he decided to try a technique he’d used once before, back when he photographed his Beat Generation comrades—an off-camera flash. “I had this incredible sense of power. I had all these wealthy people, and I was working it,” he recalls. “I had this light. I could see it probing expressionistically through this space and time.”

Intrigued by the results, he got himself invited to other society events. “I got it into my Marxist mind that this was important work,” he says. “I just assumed the revolution was coming and it would wipe out this social class, so I had to document them before they were gone.”

Fink certainly arrived at the festivities in proletarian style. “I had a 1957 Willys Jeep truck that didn’t go over 40 miles an hour, and I would dress up in a tuxedo, jump in that truck, drive four hours from my home in Pennsylvania to get to some soiree on Park Avenue, get in there and immediately have 17 gin and tonics because I was so nervous, metabolize it instantly and proceed in a more friendly state and work the whole night through. Then I’d get back into the truck and drive back to Pennsylvania and develop the film before dawn. I’ll tell you what,” he says, “I was one obsessed monkey.”

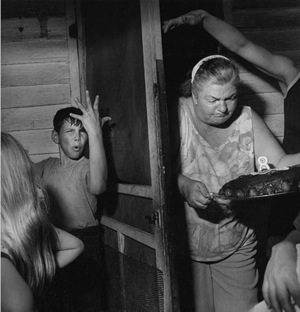

Fink says that the idea of combining his images of high-society bashes with those of the Sabatine family of rural Pennsylvania in Social Graces was not a Marxist plot. “It was more organic, rather than political,” he says. “For me, the photograph always follows the human.” Fink got to know the Sabatines simply because he needed a lawnmower. “John Sabatine had a lawn mower shop, and he sold them cheap, so I went down there,” Fink says. “I ended up developing a close relationship with the Sabatine family, and I photographed them because they liked it.”

For that matter, the people in Fink’s society-ball photographs also seem to have liked being photographed. Perhaps it’s because they were enjoying their parties, but more likely it was something about Fink himself.

“I don’t know what it is,” he says. “I’m a scoundrel, really. But there’s something about me that remains rather innocent when I’m looking at people. I don’t have a judgment factor about people, and I don’t think about using them as commodities. Also, I’m always slightly nervous when I’m taking a picture, though I do it obsessively and without shame. People may sense that and relax, or at least not feel threatened.”

He adds that his anxiety when photographing people is social in nature, not artistic. “I’m not nervous about whether I will get a good picture,” he says. “It’s about not wanting offend anybody, and not being quite so invasive as I can be. If I get a good picture, that’s great.”

Power, Corruption and High Drama

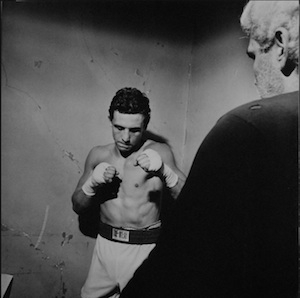

Social Graces changed Fink’s life. “I went from being underground to overground in a hurry,” he says. It also had an impact on many young people who encountered the book while studying in the college photography programs that were proliferating in the late 1970s and early 1980s. One was Kathleen Klech, who later became the longtime photo editor of Conde Nast Traveler. Klech, who is now senior residential advisor at The Modern Group in New York, started her career in the 1980s as photo editor of a spirited new publication called Manhattan Inc. Straight out of college, she didn’t really know much about magazines, but she did know about fine-art photography, and when a story about heavyweight boxing champion Mike Tyson crossed her desk, she wanted Larry Fink to illustrate it.

“She said, ‘What’s up? Are you working? Can I ask you to work for a magazine?’” recalls Fink. “At the time, my Guggenheim grant was running out, and my marriage was ending, and I was busted. So I said, 'Yeah, you can get me to work.’”

Two things happened: First, Fink became obsessed by a new subject, the world of boxing, which he then spent several years photographing. “What drew me to it were the themes of power, corruption and redemption,” he says. “I like things where there’s high drama, where people live their passions out, and their fears.”

Klech says she wasn’t surprised that Fink became intrigued by boxing. “Larry’s got the true heart of a documentary photographer,” she says. “These guys, once they get interested in a subject, they can go deep. They can see that there’s much more to explore.”

The other result of the job for Manhattan Inc. was that Fink began to merge his fine-art career with magazine work. These days, that wouldn’t be considered unusual, notes Klech, who over the years has made editorial assignments to fine-art photographers like Philip-Lorca diCorca, Richard Misrach, and Mark Klett. “But back in the ’80s no one was doing that.”

Fink went on to cover fashion shows and Hollywood parties for magazines, his flash always probing beyond the artifice of events. He did the same in 2008 when he covered the presidential primary duel between Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama for Vanity Fair. He loved working for the magazine.

“I’ve never been treated so well in my life,” he says. “That’s something I don’t want to make a habit of.”

The difference between Fink’s editorial work and his fine-art work is indistinguishable. His pictures of the Obama campaign, for instance, were later shown at New York’s Pace/MacGill Gallery. “I always work with an alternative point of position, and my ambition is not to please the client first, it’s to please me first,” he says.

His point of view also pervades the series of photographs he made of praying mantises on his Pennsylvania farm—work collected in the book Primal Elegance. “If you look at some of the social posturing of the upper class,” he says, “the mantis has them beat hands down.”

Fink says the role that he is most committed to is teaching. “My approach is to assemble an avenue for passions to be expressed,” he says. “I want students to understand that there are no good pictures taken when your camera is pointed at subject matter you’re not interested in.”

Fink has found a world of subjects to be interested in, some in the rarified upper atmosphere of society, some right down the road from his home. He photographed them all with curiosity and care, managing to see them from the outside in and the inside out.