Allen Crawford: The Q&A

Q: What are some of your favorite things about living and working in Philadelphia?

A: I was born in Eastern Kentucky, but I grew up in a bay town in Southern New Jersey. I now live in a small Quaker town just outside of Philadelphia, on the edge of the New Jersey Pine Barrens.

My proximity to these overlooked wild areas and the forgotten fragments of history informs much of my work. The perimeter gives you fresh material.

Q: How did you first become interested in art and illustration?

A: I was always interested in art and design. As a kid, I was more interested in abstract painting than figurative art: Rothko made sense to me, because his paintings were evocative of the landscapes at the Jersey Shore: nothing but sea and sky. I liked Rothko’s totemic power and mystery.

I’ve always had many interests, so my focus often shifts to other endeavors for a while—but I always return to illustration. I’m a jack-of-all-trades and I know a little about a lot of different subjects. It lessens your impact in any one field, but it keeps you excited about getting up in the morning.

Q: Do you keep a sketchbook? What is the balance between the art you create on paper versus In the computer?

A: I use the serendipity method: I have sketchbooks in every room of the house. Whenever I have an idea, I just jot down or doodle into the nearest sketchbook. I’m very random about what I put in them, and how often. This leads to some interesting juxtapositions at times.

For the Whitman book project, I had the best of intentions: I had a sketchbook at the ready, but I used it sparingly, or only when I was stuck. The

working pace of this book project was so brisk that I had to skip the thumbnail stage and go directly to sketching the layout. It often took me most of the day to come up with a solution I thought was

solid, but I needed to wrestle with the scale of the final art right away in order to finish two pages per day. I’d still be working on this book, otherwise. Working that way maintained the

immediacy for me, though: the book itself is the sketchbook, really. It’s a record of the journey through Whitman’s poem.

Q: What is the most important item in your studio?

A: I move around the house when I work (I have a work station in the basement as well as the second floor), so my laptop is a constant companion, even when I’m not working on it.

I listen to a lot of history podcasts and audiobooks when I get deep into a long-term project. Over the term of making the Whitman book, I polished off Moby Dick,Ulysses, Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, and Whitman’s Specimen Days. I’m also a fan of Jonathan Meades, the BBC architecture critic and TV host. His television programs are always really entertaining and informative.

Q: As a child, what was your favorite book?

A: When I was very young, I really loved that Sesame Street book, The Monster at the End of This Book. I think what excited me most was the book became more than a surface, or a window: in my mind it became a door, a bridge. If I read this book the right way I could actually meet Grover! That was a very thrilling prospect for me, and I now try to replicate that effect in my own books. I want them to enable you to have a foot in two worlds at once.

For a while I devoured the anthologies of Ripley’s Believe It or Not! and The Guinness Book of World Records. Then I went through a Poor Richard’s Almanack phase.The How and Why Wonder Book series was a staple, too. I think that’s where I really learned to love diagrams and systematics.

I also loved going through the piles of old National Geographic issues we had lying around the house. Some dated back to the 1930’s. I still have no idea where they came from. My father was an elementary school teacher, so he probably brought them home when the library was clearing out their old stuff. There were some pretty harsh images in those issues, but they fascinated me.

Q: What is the best book you’ve recently read?

I’ve just re-read a favorite, W.G. Sebald’s Rings of Saturn. It’s a marvelous fever-dream of a book: it manages to be serene while retaining your fascination. The beautifully-crafted sentences are such a rarity: most writers now adopt this awkward, clipped writing style that feels like they’re slamming on the brakes every fifty feet, but Sebald mastered the ability to run a nearly endless sentence that allows your mind to flow unimpeded. It’s a great achievement.

I’ve also read Peter Freuchen’s matter-of-fact account of living in the Arctic among the Inuit. Just the incredible descriptions of how they would make their sleds from the frozen meat of caribou and fish was worth the price of admission. It’s a frank, brutal, fascinating read. I couldn’t put it down.

I’m currently very interested in the late American haiku poet, Nick Virgilio, who is buried 100 feet from Whitman, in Camden. He was a master of the form, introduced a gritty, urban blue-collar perspective. Lived most of his life in Camden. He was a blue-collar guy, not a polished grad school type. His work maintains a raw vigor and freshness for that reason, I think. I’ve seen the archive at Rutgers Camden when I visited to do a talk there: thousands of poems that no one has seen yet. I think his posthumous stature as a great poet will grow in the coming decades once the better part of his work is finally published.

Q: Who and what are some of your strongest influences?

A: I tend to look outside of illustration and design, but my earliest influences were mostly from the mid-twentieth century: Milton Glaser, El Lizzitsky, Alvin Lustig, HerbLubalin, Charles and Ray Eames, Reid Miles, Roy Kuhlman, Alexander Girard, the usual suspects.

Like anyone else, my influences eventually widened: Hiroshige, Alphonse Mucha, Richard Diebenkorn, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Italo Calvino, A.G. Rizzoli, Erte, WinsorMcCay, Joseph Cornell, Alan E. Cober, Momus, William Carlos Williams, Moebius, Alexander Calder, Harry Partch, Chris Ware, Rockwell Kent, John Berryman, Sevres porcelain, bottle whimsies, Arte Povera, brutalism, Early 19th-Century naturalist plates, old boardgames, oceanside motels, the forms and color palettes in living things…it changes from week to week.

Q: What was your first professional assignment and how did you get it?

A: It’s impossible for me to remember my very first professional assignment, to be honest.

I’ve been a designer/illustrator for twenty-five years, and my introduction into both design and illustration were gradual. Over the years I’ve designed swizzlesticks, key chains,

pocket squares, CDs, two-headed dolls, you name it. I once even designed a billboard covered in pink sequins. I did an awful lot of illustrations in various styles when I worked a day job as a

designer, so the transition into full-time illustration was pretty seamless.

Q: What was the last art exhibition you saw and what did you take away from it?

A: The Philadelphia Museum of Art recently has a small side room in their modern wing for their films and video art installations. This spring it’s home to Zoodram 5, a delightful piece by French artist Pierre Huyghe [French, b. 1962]. It consists of a large aquarium tank full of large red stones, both floating and stationary. Inside the tank lives a giant red hermit crab that has taken a small golden replica of Brancusi’s sculpture Sleeping Muse for a shell. It shares this Martian dreamscape with a dozen skittering arrow crabs, whose limbs look like bloody needles. Sitting in the dark for an hour in front of this tank was a delight. It reminded me of Max Ernst of course, but it also reminded me of Raymond Roussel’s proto-surrealist book, Locus Solus, which goes into all sorts of exhaustive descriptions of surreal, disturbing tableaus.

I’ve heard that the New York Times trashed the Korean art exhibition at PMA, but I loved it. There was one old ceramic piece in the show that was on display called a moon vase, which was intentionally cut in half and reassembled, causing a slight distortion in the vase. The vase assumed a different silhouette whenever you changed your position. I was really taken by it. There were also some portraits of military scholars on display, one of whom had blue eyes, which intrigued the hell out of me.

Q: What is your favorite part of the creative process?

A: I get a charge out of sharing the final product, but I really enjoy the research. I love a project that allows me to exercise my curiosity. Being a designer/illustrator is an ideal profession if you’re interested in everything: it’s a vital part the job, in my opinion.

When my wife Susan and I did the new identification key illustrations for the Milstein Hall of Ocean Life [at the American Museum of Natural History], we had to rely on the knowledge of marine animals that we had accumulated over our lifetimes. It became crucial to the success of the project, because the scientists could trust us to understand what they were talking about, and that kept things running at a brisk pace. At one point we were receiving videotapes (remember those?) from the ALVIN submersible at Woods Hole of deep sea species that were previously unknown to science. It was very exciting. Probably the most fulfilling project we’ve ever worked on. I wept a little when the Hall reopened.

I often try to avoid what is considered “the canon.” I think that in some cases, selective ignorance can be useful. It forces you to circumvent the gaps in your knowledge, which takes you into more obscure areas of interest and influences that you otherwise wouldn’t discover. This method forms strands of association that allow you to come up with solutions that you otherwise wouldn’t.

I don’t think I’m terribly talented in any one particular thing, but I’m reasonably well-versed in a variety of pursuits, which gives me a great deal of versatility and has allowed me to amass an interesting skill set and an eclectic body of knowledge, which constitutes a talent in itself.

I really don’t like to repeat myself. Perhaps it’s not the best trait to have if you’re an illustrator, but doing the same thing over and over bores me. I’m most interested in projects that I’m not quite sure I can pull off.

What is/would be your karaoke song—and why?

Well, it’s a toss-up between The Mighty Hannibal and Arthur Brown. I’m a song-and-dance man at heart.

What is your hobby?

My life consists of hobbies that are occasionally remunerative. I’m always on the lookout for a new obsession. At the present time it’s botany, architecture, industrial history, horticulture, and how they intersect with one another.

I’m an amateur naturalist and I do a lot of volunteer conservation work in the Pine Barrens, scouting remote areas and monitoring the condition of the various species, mainly rare orchids, carnivorous plants, turtles, and tree frogs. Some of these species live nowhere else on Earth. I’ve had Lyme disease about three times, but I’ve always caught it early.

A couple years ago I did a solo three-day kayak trip from my house to West Philly. Almost got plowed over by a tanker in the Delaware, paddled up to an aircraft carrier and touched the hull, found wooded lagoons that were once the piers for the largest rail yard in the country. It was a great little adventure.

Q: What was the most difficult part about getting from idea for the book to the finished art?

A: I’m a writer as well as a designer/illustrator, but I remain very visual in my approach. Even when I’m writing a straightforward book, I need to establish the look of the book in order to help me establish the tone.

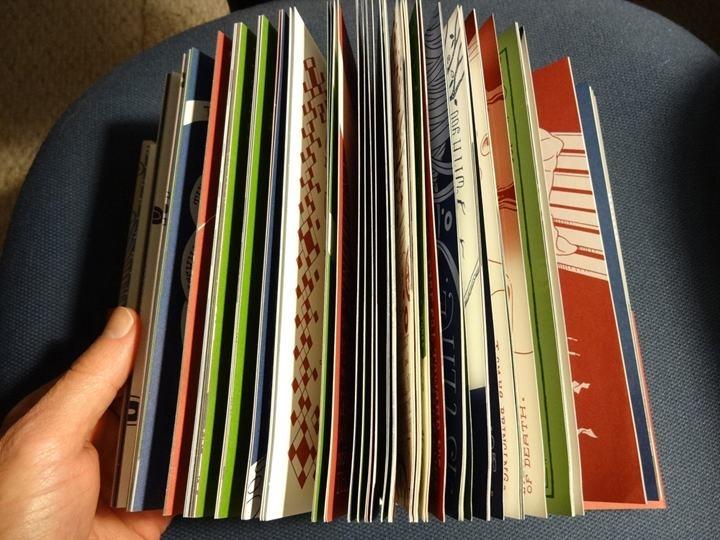

If you’re going to produce a book in print form now, you need to pull out all the stops: the book has to be an art object. It’s an end in itself, as well as a means. The reader has to revel in the book’s sensed qualities, or she isn’t getting her money’s worth. The reader may as well opt for its digital form, instead.

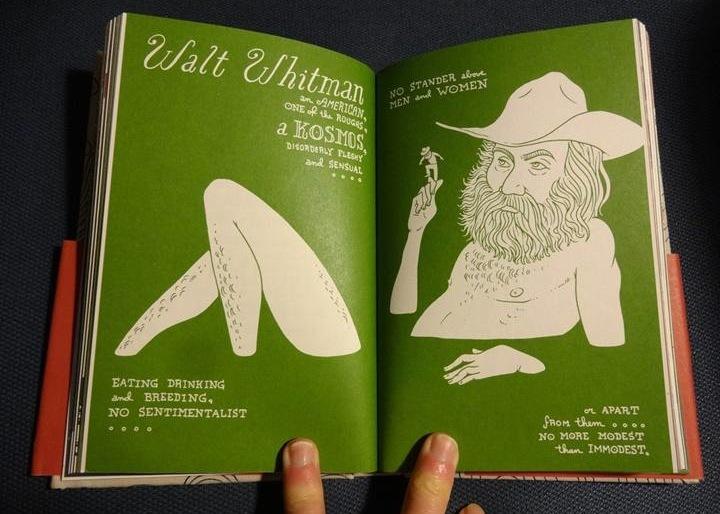

For my latest book, Whitman Illuminated: Song of Myself, the physical form of the book is central, and is designed to influence how you experience the poem. The way the poem is written and illustrated is very dense in places, so it slows you down, forces you to take your time with each line. Ideally, I’d like readers to take a few months to read the entire thing, to take in a spread each day.

The 1855 version of “Song of Myself” is the most radical and uncompromising: it’s a torrent of verse. The versions of “Song of Myself” that followed in successive editions of Leaves of Grass become more structured and conventional in their form. I wanted to make a version of “Song of Myself” that was even more unrestrained than the original 1855 version.

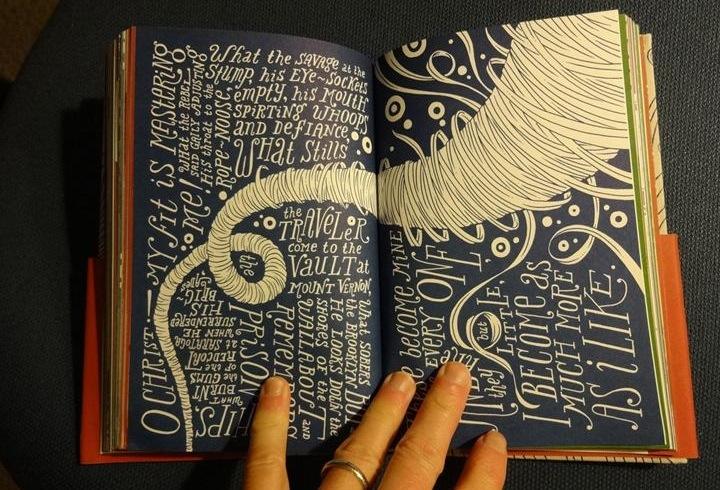

Each spread in the book has a different feel, because I’ve grouped the

verse paragraphs so that a subject, thought, or image is usually complete before you move on to the next spread. The book is also small enough to rotate in your lap, so that you can read the type as

it curls around the images.

The book plays with Whitman’s early method of moving lines around in blocks, what the Whitman scholar Ed Folsom calls “the portable line.” “Song of Myself” is comprised of the early notes that Whitman wrote over the years on the Brooklyn ferry and the Manhattan omnibus. Whitman later composed these notes into clusters of verse that eventually appeared in Leaves of Grass. In my book, Whitman’s poem is viewed as well as read: the sequential order of the lines is of secondary importance to the overall drift of the verse. In fact, you can read the book in multiple ways, coming away with a new poem each time.

I had to establish the look of the interior before my publisher, Tin House, was convinced that this would be a compelling project. I almost gave up, but then I woke up one morning and had the solution in my head.

The book’s visual style had to be compatible with Whitman’s aesthetic, so I came up with a very simple solution: hand-drawn images, flat colors, nothing too fussy.

There was an athletic aspect to making the book: I was in my basement for an entire year, contorting myself as I worked. I had to stop for a day on a couple occasions, just to recover. The cold also did a number on my knees, which are becoming slightly arthritic.

My first book, The Affected Provincial’s Companion, Vol. I, was also an intensely visual sort of book, but very different: clean, humorous, diagrammatical.

With the Whitman book, I hope to establish a wide thematic and stylistic range for myself, so I don’t get pigeonholed into just one kind of project in the future.

Q: What would be your last supper?

A: An ortolan bunting would be very poetic, but I’m too fond of birds.

I’ve never dabbled in drugs, but I suppose I’d like a cap of psilocybin as a final meal. It gives me something to look forward to before I disembark for The Great Perhaps.

Q: What advice would you give to a young artist about choosing an art school or college?

A: I attended a small liberal arts state college, so my perspective is rather limited and biased. In general, it seems to me that if you want to be a skilled and versatile artist, you need to strike a balance between honing your craft and attaining a comprehensive grounding in a variety of subjects. To thrive in any creative field, you need a deft hand and a sharp mind. But times change, and you need all kinds of contingencies to stay viable over the long term.

Being a freelance artist is like building a trapeze while you’re swinging on it. It’s a precarious way to make a living, but if you can somehow manage to persevere, it’s a great way to make a life.

Allen Crawford will give a talk and sign copies of Walt Whitman Illustrated: Song of Myself at the Society of Illustrators on May

21st, 6:30-8:30. 128 East 63rd Street, NY, NY. Tickets. The following week

he will be at Housing Works Bookstore Cafe, New York, May

27th from 7-8:30; and on Friday, May 30th at 2 pm, he will be signing books at Book Expo America at

the Javits Center, New York.

See Walt Whitman Illustrated in New York Times Metro Section here.

Allen Crawford is a designer, illustrator, and writer. In 1996, Allen and his wife Susan founded their studio, Plankton Art Co. Their studio’s most notable project to date is the collection of 400 species identification illustrations that are on permanent display at the American Museum of Natural History’s Milstein Hall of Ocean Life in New York. Under the pseudonym “Lord Breaulove Swells Whimsy” Allen wrote, designed, and illustrated The Affected Provincial’s Companion, Volume One (Bloomsbury 2006), which was optioned for film by Johnny Depp’s production company, Infinitum Nihil. Metrolit Verlag in Berlin has recently published a German edition. Allen’s latest book, Whitman Illuminated: Song of Myself (Tin House Books) is an illustrated, hand-lettered, 256-page edition of Walt Whitman’s iconic poem. It’s scheduled for release on May 13, 2014. (Preorders of the book can be made here.) Selections from Whitman Illuminated: Song of Myself will be featured in American Illustration 33. Allen’s work has also appeared in The New York Times, Interview, Orion, Frieze, Vice, Tin House, and Art in America. Plankton Art Co / Twitter / Facebook / Pinterest