Photography and The American Civil War

Most of what we know about photography in America today, nearly 175 years after it was introduced, was shaped by the work done by over 1,000 photographers who created indelible images during the Civil War, of the people, the conflict and uncertainty they experienced between 1861 and 1865, and the landscape of a pre-industrialized America.

Photography and the American Civil War opens tomorrow at the New Orleans Museum of Art. Among the exhibition’s purposes, outlined by curator Jeff L. Rosenheim, who organized the exhibition for the Metropolitan Museum of Art last year, is to show how the young medium helped to shape a young country’s image of itself. The collection of more than 200 photographs that define one of history’s most defining moments brilliantly makes this evident.

When photography arrived in America in 1839, photo studios quickly sprang up in all the major cities. Soon thereafter, even small towns had photo studios, sometimes set up in the back of local barbershops. By the late 1850s, getting a portrait done for posterity had become a regular part of American life, and cartes de visite, inexpensive little prints, were within the reach of nearly everyone. After shots were fired on Fort Sumter in April 1861, when thousands of soldiers mustered into the Union and Confederate Armies, it was a given that the new conscripts would don their uniforms and head for the portrait studio before going to war. Although the soldiers could not have known it at the time, 750,000 lives would eventually be lost, or one in five who went into battle.

The exhibition starts out with photographs of people from all walks of life, from portraits of soldiers and officers—alone, in pairs, and in groups, to Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 presidential campaign photographs. In the first gallery is a picture of the abolitionist and human rights activist Sojourner Truth. A former slave from New York State, she sold photographs of herself to raise money to educate emancipated slaves and to support widows, orphans, and the wounded. Nearby is a case full of golden lockets with tintype portraits of soldiers, made as keepsakes for loved ones.

While the names most often

associated with photography of the era include Matthew Brady, Alexander Gardner, George N. Bernard, and Timothy O’Sullivan, in fact there were over 1,000 photographers who took to the bloody

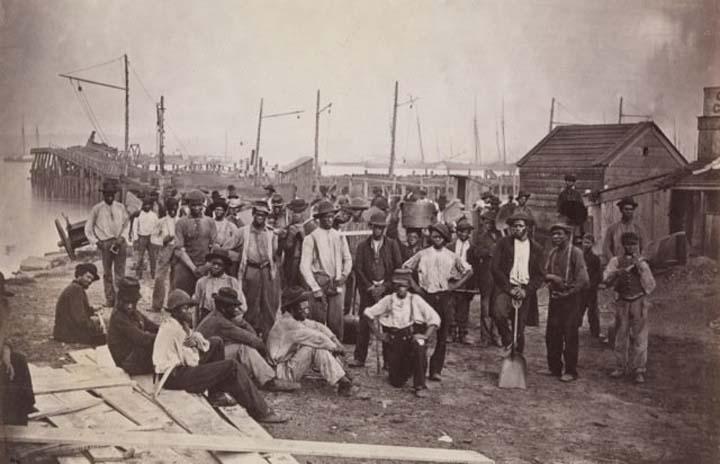

battlefields with their cameras. Andrew Joseph Russell, a photographer from New Hampshire who signed up with the Union Army and became an official field photographer, captured a group of black

laborers at the Quartermaster’s Wharf in Alexandria, Virginia, in 1864 (above). These men, likely former slaves, are seen here in a new light.

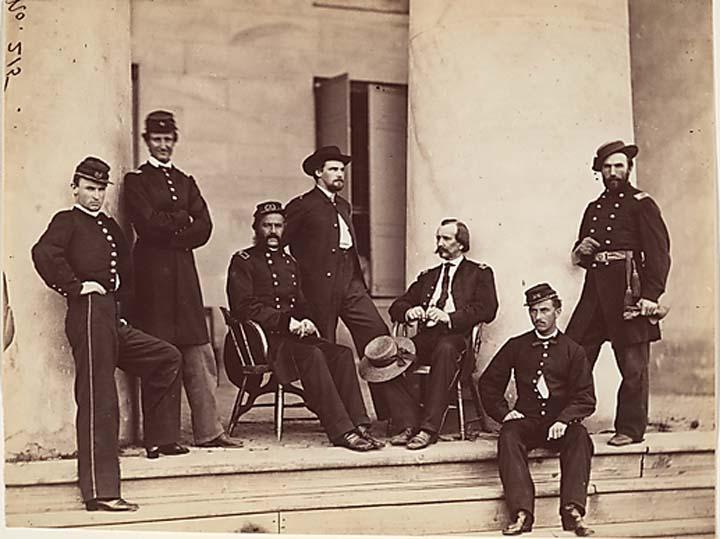

A strangely unsettling group portrait by Alexander Gardner depicts Brigadier General Gustavus A. DeRussy and his staff at Arlington House, Arlington, Virginia, also from 1864 (below). Although the seven men in the picture strike oddly casual poses, some with jackets unbuttoned, one with a woman's beribboned straw hat resting on his knee, and one smiling at the camera, the hierarchy of 19th-century military portraits makes evident which one is DeRussy. The more one learns about the history of the house—the former residence of Robert E. Lee, who fled his home soon after the fall of Fort Sumter, and who turned down an offer from President Lincoln to take command of the Union Army—the stranger this possibly jeering tableau becomes.

The show also presents remarkable images included in the two great wartime albums of original

photographs, which can be seen as the first American photobooks: Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of War and George N. Barnard’s Photographic Views of

Sherman’s Campaign, both released in 1866. The former publication includes 100 views commissioned, sequenced, and annotated by Alexander Gardner. This two-volume opus provides an epic

documentation of the war seen through the photographs of 11 artists, including Gardner himself.

The second publication includes 61 large-format views by a single artist, George N. Barnard, who followed the army campaign of one general, William Tecumseh Sherman, in the final months of the war—the “March to the Sea” from Tennessee to Georgia in 1864 and 1865. The exhibition explores how different Barnard’s photographs are from those in Gardner’s Sketch Book, and how distinctly Barnard used the camera to serve a nation trying to heal itself after four long years of war and brother-versus-brother bitterness.

While bloody battlefields littered with corpses are a frequent subject in images of the period, the exhibition also presents a group of medical photographs from the Stanley B. Burns Collection that are less well known and rarely on display. Made by Dr. Reed Brockway Bontecou, these pictures of battlefield casualties were intended to serve as teaching tools rather than as war records, and became the largest medical photography collection of its kind. These images of men with amputated limbs, and the discards from their surgeries, have only recently been matched for their heartbreaking truths by photographs from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Alexander Gardner, Ruins of the Gallego Flour Mills,

Richmond, 1865. All photographs © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Alexander Gardner, Ruins of the Gallego Flour Mills,

Richmond, 1865. All photographs © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Photography and the American Civil War, opening January 31 and continuing through May 4th at the New Orleans Museum of Art. One Collins Diboll Circle, City Park, New Orleans, LA. Information.

Save the date: Friday, January 31, 6 pm: Gallery Talk with Russell Lord and Jeff Rosenheim: Photography and the American Civil War. Information.