Robin Hammond: 2013 Smith Award

The deadline for the 2014 W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic Photography is May 31, 2014. Considered one of the most honorific awards in photojournalism, the prize grants $30,000 to an individual photographer to complete a work in process. The 2013 winner is Robin Hammond, a 37-year-old freelance photojournalist born in New Zealand. He has been part of the photo agency Panos Pictures since 2007. Following is the 2013 interview he did with FotoEvidence editor, Svetlana Bachevanova.

SB. Why did you decide to work on a project related to mental health in Africa?

RH. I was in Juba, South Sudan to cover the referendum for Independence. There were many photographers and journalists there from around

the world. I had to find something other than the rallies and ballot box pictures that everyone else would be shooting. The journalist I was working with and I were in the car debating how we could

tell this story in a different way when I saw a mentally disabled girl begging on the side of the road.

I asked our driver what treatment there was for mentally disabled people in Juba. He

casually replied that they were put in the prison. Our story became about the price South Sudan had to pay for independence. In particular, we focused on what happens to the most vulnerable in

communities when war destroys infrastructure and the ability to provide social services. The images of mentally disabled men and women shackled in Juba Central Prison were a stark illustration of the

cost of war.

Juba, Sudan. January 2011. Photo © Robin Hammond.

Juba, Sudan. January 2011. Photo © Robin Hammond.

Unfortunately

it is not just Sudan that has been through difficult times. I set out to investigate the mental health impacts of conflict and crises on other sub-Saharan countries.The media rarely considers the

long-term impacts of war, famine and displacement. Westerners have long been aware of the trauma of war on their own troops and civilians caught up in disaster. Africans do not suffer any less. I

thought this was an important story that needed to be told.

SB. You wrote, “After 12 years of documenting human rights issues, I’ve never come across a greater assault on human dignity.” What did you witnessed that made you say this?

RH. Not only was the severity of the cases of abuse and neglect great, but I was overwhelmed by the scale. Over and over again I saw people denied their liberty – restraining mentally disabled men, women, and children seemed the first and often only form of ‘treatment.’ Everywhere I went I found an entire section of the society in chains. They are easily marginalized. They are not allowed to advocate for themselves. The vast majority of the people I met are acutely aware that they are being deprived of their rights, but their arguments are written off as the ramblings of ‘mad people.’ There is no greater population of marginalized and voiceless people on earth than the mentally disabled

SB. Your project takes the viewer right into the lives of the people affected by mental illnesses? How were you able to gain access?

RH. Different situations required different strategies. Some people were resistant, suspicious of my presence, but generally I would explain to those caring for, or incarcerating, the people I photographed what I was doing and they would show me around their facility. Many didn’t see their treatment of people with mental disability as abusive. It is, in a way, even more disturbing that they considered their treatment as normal and in no way cruel.

This 14 year old boy has been

tied up for six years. His mother refuses to have him admitted to Gulu Hospital, which is only two kilometers away. Gulu, Northern Uganda. April 2011. Photo © Robin Hammond.

This 14 year old boy has been

tied up for six years. His mother refuses to have him admitted to Gulu Hospital, which is only two kilometers away. Gulu, Northern Uganda. April 2011. Photo © Robin Hammond.

SB. Did you have the chance to speak with some of the medical personal in these places? What is their view of the way the mentally ill are treated?

RH. I always spoke to those responsible for the care of the mentally disabled in the places I visited. Some of those were medical personnel, others were religious or traditional healers. Prison guards were the caretakers in Juba Prison. In many cases, family members must care for their mentally disabled relative without any assistance. I went to non-governmental organizations, government facilities, refugee camps, villages, slums. The attitudes varied from place to place, person to person. Many people think mental illness has a spiritual cause and therefore seek spiritual remedy. Imams, pastors, and traditional healers strongly believe they are curing the sick. Sometimes they can be the only people in a community giving any kind of positive attention to the mentally disabled. Unfortunately their treatment can also be very harmful.

Those with a medical background are often frustrated by the lack of resources they have, especially when it comes to the provision of medications. I met with a mental health clinician here in Liberia that has been able to turn around the lives of hundreds of people in his region. The non-governmental organization providing the drugs is ending its program in August. The Liberian government is supposed to take over provision but the medical personnel I met say it won’t happen. Their patients are terrified of having to go back to the lives they were leading before.Then there are those who are merely caretakers. The prison warden of Juba Central Prison was very clear – this was the wrong place and they were the wrong people to be caring for the country’s mentally ill, but they had no choice.

SB. The way a nation treats its mentally disabled can be a good indicator of the quality of its society. Did you find this to be the case?

RH. I’m not sure how one measures the quality of a society and personally I would hesitate to relate it to the treatment of the mentally ill. I do think though that the mental health of a society and its attitudes towards it are interconnected with the events it experiences. The crises these countries have been through have caused mental illnesses and simultaneously destroyed the resources and facilities designed to care for the mentally disabled. Both Monrovia in Liberia and Mogadishu in Somalia had state of the art mental health facilities before they were destroyed in war. In disaster, education is also weakened, which results in a lack of knowledge about mental health. It also drives away mental health professionals who would otherwise be able to provide care and teach their societies about it.

SB. The way mental illness is treated remains a problem in Africa. Do you think your presence as a photographer touched the lives of any of your subjects?

RH. The way mental illness is treated is a global problem but especially challenging in countries going through or coming out of crises. Unfortunately Africa has seen more than its fair share of disaster. My presence did touch the lives of some of my subjects. I wish I could have helped more. [More]

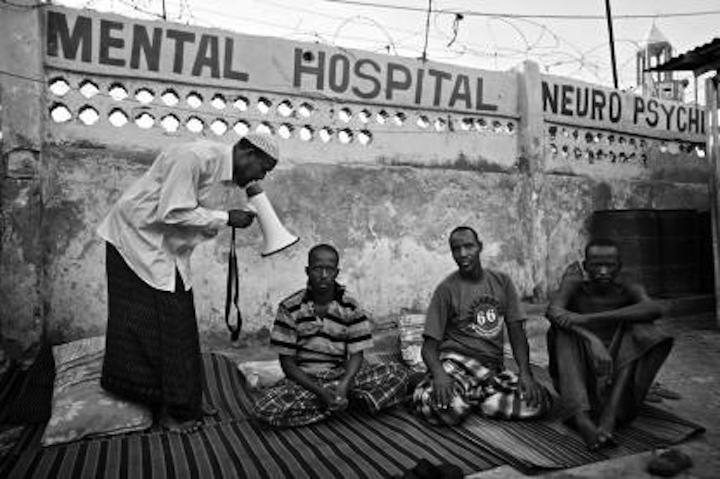

Many Somalis will take their mentally ill relative to traditional or Khoranic healers for treatment.

Mogadishu, Somalia. May 2011. Photo © Robin Hammond.

Many Somalis will take their mentally ill relative to traditional or Khoranic healers for treatment.

Mogadishu, Somalia. May 2011. Photo © Robin Hammond.

The winner of four Amnesty International awards for Human Rights journalism, Robin Hammond has dedicated his career to documenting human rights and development issues around the world, but especially in sub-Saharan Africa.

In 2011 Hammond won the Carmignac Gestion Photojournalism Award which allowed him to document in Zimbabwe for four months. Actes Sud published a book of the photos to coincide with an exhibition of the work in Paris in November 2012. In 2013 he won the FotoEvidence book award that will result in the publication of his long term project on mental health in Africa, Condemned.

W.

Eugene Smith was a photographic essayist who is remembered for his concerned photography and the dedicated compassion he exhibited during his forty-five-year career. The W. Eugene Smith Grant in

Humanistic Photography, established in 1978, is presented annually to a photographer whose past work and proposed project, as judged by a panel of experts, follows that tradition.

Submissions for this year’s grant are accepted until May 31, 2014. This year’s recipient will be announced on Wednesday, October 15, at a ceremony at the SVA Theatre, 333 West 23rd

Street, New York. Admission is free. For more information, see smithfund.org.

Save the date: The W. Eugene Smith Foundation presents, 6:30 pm: At the Top of the World | Photography: Kira

Pollack in Conversation with Jonathan D. Woods. Aperture Gallery and Bookstore, 547 West 27th Street, 4th Floor, NY, NY. $5 donation/Free. Information.