Photographer Profile - Aristide Economopoulos: "I'm still the one who's able to tell the stories"

|

|

|

“I’ll essentially be the only photographer from my newspaper there,” he noted.

For most of the past 16 years, Economopoulos worked for the Newark Star-Ledger, which under former assistant managing editor Pim Van Hemmen earned distinction for its visual journalism. Econompoulos was part of a team that won the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News for its coverage of the resignation of New Jersey Governor James McGreevey, who left office after disclosing that he had carried on an adulterous affair with a male lover.

Today Economopoulos is still doing what newspaper photographers do — capturing daily life, covering local and state politics, documenting small triumphs and large tragedies and sometimes taking off to shoot national stories, like the inauguration of a new president. But he’s not working for the the Star-Ledger, strictly speaking. For the past two years his employer has been an entity called New Jersey Advance Media, which creates content for the Star-Ledger and the website NJ.com, both of which are part of the the Advance Publications newspaper chain.

The reorganization of the company reflected the modern realities of the newspaper business in general, which, with rise of the internet and social media, has seen readership and advertising revenues decline. And it has had a significant impact on how Econompoulos works.

Most of the photos he shoots now are for the website. “There are three times as many stories online as in print,” he says. “We’re encouraged to create large galleries for the site.” There has also been downsizing.

“We went from 28 photographers to six,” Economopoulos says. “Our newsroom used to be 300 something, and now it’s 80 something, and we no longer have photo editors. I miss them. There’s no one working with you and fighting for you now.”

Economopoulos estimates that more than half of the stories he works on now are self-assigned. “In one way, it gives me more flexibility as a journalist, but on the other hand there’s pressure to produce a lot of content and to find stories that will get a lot of hits online,” he says. “Sixty percent of my performance review is based on web hits and only 10 percent is based on the quality of my work.”

But, he adds, there is still a paycheck every other week. And there are still opportunities to do great work. “If you had talked to me a year ago, it would have been like the sky is falling. It’s not the same, but I’m producing work I’m proud of,” he says.

The Life and Times of a Newspaper Photographer

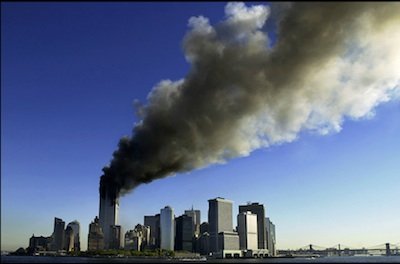

He has much to be proud of: Economopoulos’s work over the years has won awards from the World Press Photo and Sony World Photography competitions and has been selected for both the PDN Annual and the American Photography annual. He a six-time winner of the Photographer of the Year award from the New York Press Photographers Association, and his pictures of the 2001 terrorist attack are on permanent display at the National September 11 Memorial Museum in Manhattan.

Economopoulos has photographed prom nights and street shootings, Miss America pageants and cancer patients, protests and plenty of politicians, including New Jersey Governor Chris Christie.

“He’s fascinating,” Economopoulos says. “He’s one of the nicest, charming people, and then he’s got this other side. And I just cover it all. I know he loves some of my photos, and I know for a fact that he hates some of my photos. And guess what — he thanked me one time for being fair.”

Economopoulos says he thrives on the challenge of producing good work from the most mundane-sounding stories. “I figure if you can’t find a good story in your back yard, you can’t find a story anywhere,” he says.

Several years ago, he started covering the Far Hill Race Meeting, aka The Hunt, an annual steeplechase horserace held annually in Far Hills, New Jersey, where some 50,000 people show up to party and be seen. “Of those 50,000 people maybe 5,000 actually see a horse,” Economopoulos says. “Imagine your moneyed Hamptons crowd rubbing shoulders with drunks from the Jersey Shore. You have to have people skills to cover it, because if some guy who’s been drinking all day gets in your face, you’re not going to get a good picture.”

Econompopoulos’s coverage of The Hunt turned out to be popular — his online gallery of the event has gotten more than a million views. “In its own way it’s also an important perspective on society, and I’m proud of it on that account,” he says. He’s also proud of an extensive photo essay he shot in 2011 called “A Week in the Killing Cycle.” The gritty documentary project focused on urban crime in Newark and the work of the Essex County Homicide Task Force.

Sometimes, there’s no avoiding a story: After Hurricane Sandy slammed into the Jersey Shore in 2012, Economopoulos found his way to Union Beach, a blue-collar town of about 6,000 people that was hit especially hard but remained largely overlooked by the national media. The National Guard had closed off the town, but Economopoulos got in by attaching himself to a group from the ASPCA that arrived to rescue pets lost in the storm.

He photographed a half-standing house in the town that became a symbol of Sandy’s destruction. Later, he and a reporter spent two months working on a project about people in Union Beach trying to put their lives back together.

At Work With Camera In Hand

Economopoulos grew up in Bethesda, Maryland, discovered photography in high school and went on to study it at the Rochester Institute of Technology. After graduating he moved back to Bethesda and freelanced for the Washington Post. “But I felt like a small fish in a big pond,” he says.

He spent two years learning his trade at the Dubois County Herald in Jasper, Indiana, and another two years at the State Journal-Register in Springfield, Illinois. Then he was recruited by the Star-Ledger. The decline of local newspapers across the country denies young photojournalists that kind of traditional training ground.

Economopoulos had been working at the Star-Ledger for 10 months when he got a call from an assignment editor one morning telling him that a plane had flown into the World Trade Center. By 9:15 he was in Manhattan, photographing the burning towers. He was at the corner of Church and Dey streets when he heard a metallic groaning sound, looked up, and saw the North Tower collapsing on top of him.

“It was a matter of flipping the switch from taking pictures to running,” he says. “The hard part is flipping the switch back.” Economopoulos came away with dust-damaged retinas and what he says was “bad PTSD.”

You can find his entire account of 9/11 archived online by the NYPPA.

The newspaper business is vastly different from what it was in 2001. The New York Times recently released an internal report that described the challenges it faces and outlining solutions — such as publishing more visual storytelling. But in an important way, the job of being a newspaper photographer hasn’t changed, says Economopoulos.

“It’s all the same when I have a camera in my hands,” he says. “I’m still the one who’s able to take the pictures and tell the stories.”