Photographer Profile - Elinor Carucci: "My ability to do things differently lies in a very deep personal area"

|

|

|

It has been a little over 20 years since Carcucci left Jerusalem and found a new home in New York City. In that time she has established herself as an influential and widely admired artist. Her first book, Closer, published in 2002 when she was still largely unknown, sold out its first printing. She was awarded the International Center of Photography's Infinity Award for Young Photographer 2001 and received a Guggenheim Fellowship the following year. Her work has appeared in a number of solo and group exhibitions and is included in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and Museum of Fine Arts in Houston.

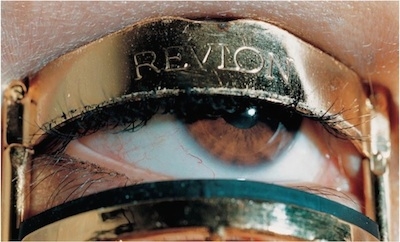

Her photography is almost immediately identifiable: Intensely emotional, it is very often self-revealing and sensual. The images in Closer were an unflinching chronicle of her own life as a daughter and wife, with subtexts about female identity, family baggage, mortality and pleasure.

“While the pictures describe the vulnerability of our aging, corporeal selves, they also describe the sensual and sexual pleasures to be had in life, seemingly right next to us, just for the asking—kissing, stroking, touching, embracing, hugging, eating, bathing, enjoying sex,” wrote curator Susan Kismaric in the book’s introduction.

Carucci’s work can be seen in the vein of emerging women artists in 1990s who, as critic Vicki Goldberg wrote in American Photo magazine in 2002, “expressed an obsession with their own bodies and emotional lives by means of the camera.”

Today, thanks to the Internet and social media, there is no shortage of platforms for photographic self-exposure. But the kind of emotional probing undertaken by Carucci remains rare. And it may be getting rarer, says Carucci.

“I feel there are fewer people photographing their lives now,” she says. “These days I see a lot of conceptual fine-art work — work that is colder. Today being emotional in fine-art work is almost not allowed. It’s allowed in music and the film industry and literature, but in fine art it became a no-no.”

Nudity As Metaphor

Carcucci’s career breakthrough came one day in the late 1997 when she walked into New York City’s Ricco/Maresca Gallery with her portfolio, unknown and unexpected. She thought she would receive a polite brush-off from a receptionist, but instead it was owner Frank Maresca sitting at the entrance desk. He looked at her work, liked it and gave her an exhibition.

“Without the show, I don’t know if I could have survived in the city much longer,” she says.

Carucci grew up interested in music and theater from a young age. She got into photography one afternoon because she didn’t have anything else to do. “I picked up my father’s camera — he was an amateur photographer — and my mom was just waking up from a nap, so I started taking pictures of her. I fell in love with the medium. I realized I was seeing so much more with the camera. I was listening with my eyes. So now I tell my own kids, who are 11, that it’s important to be bored sometimes. That’s how I discovered photography.”

After serving in the Israeli Army and then getting a BFA from Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, she decided to move to New York to launch her career. Her mother encouraged her to go.

"I was very naive about how difficult and competitive it was going to be,” Carucci says. “Once I got here, I wanted to go home, but my mother was like, ‘No, you cannot come back, because if you do you’ll never try again.’”

Carucci’s relationship with her mother is the fabric from which much of her early work is woven. “It started from her — many of my pictures were about her and her and me, and what she thought I should photograph and what I thought I should photograph,” she says. In capturing that interplay — the closeness and the inevitable struggles — Carucci created a body of work that was emotionally fulfilling and psychologically gripping, with extreme close-ups and nudity used as metaphors for intimacy.

“Tolstoy was wrong,” wrote Goldberg of Carucci’s images. “All happy families are not alike. Some are more beautiful than others and are quite aware of it; and some are more naked.”

“I don’t know why I began doing the intensely personal work and turning the camera on myself,” Carucci says. “I think it’s hard to know. It’s almost like asking why are you who you are. It think this is just how I photograph. This is what I'm drawn to in other art forms, to be very very personal, to go deeper into emotions and conflicts.”

The Art of Listening

Carucci followed her first book with Diary of a Dancer (2008), which documented her life as a professional Middle Eastern dancer performing at weddings, Bar Mitzvahs and other events — a sideline that certainly set her apart in the fine-art world. In her 2013 book Mother, she documented her life after giving birth to twins. “Some of that work, even though it’s very personal, can also be very universal,” she says. “Luckily, people can relate to the things I capture in my pictures — love, hate and all of the things that we struggle with, the daily dramas.”

Along with that personal work she took on editorial work, often shooting stories about families in crisis or facing emotional struggles — a piece for Wired, for instance, about a father’s search for medical treatment for his son with epilepsy, and a story for New York magazine about a mother who attempted to kill her autistic daughter.

“When the stories are personal and filled with drama, editors call me, and I dive in,” Carcucci says. The years she spent as a belly dancer prepared her for such work, she says: “I was performing in living rooms at weddings and parties and anniversaries. I learned how to feel the room and the families, and it’s the same when I go to someone’s home to take pictures. It’s about being sensitive and respectful, and listening to what they want to share and what they don’t.”

Listening, Carucci says, is also a key part of her job as a teacher in the graduate program at the School of Visual Arts in New York. A thesis adviser, she says she “tries to lead students into the kind of work they want to do.”

“I tell them, ‘I’m sorry, I might sound like a therapist because I'm asking them so many questions,’” she says. “My job is to try to understand the person and the work they are doing, and to try to make those two things one — the person and the work.”

Fine-art photography is a difficult profession, Carucci says, and it’s only worth the sacrifices if you are doing something you absolutely care about. “I began to do the kind of work I do because that’s where I feel alive as an artist,” she says.

Emotions may not be trendy in art now, but they are what Carucci knows, so she follows after them. “I appreciate other artists who do more intellectual or conceptual work,” she says, “but I know that my ability to do things differently lies in a very deep personal area.”