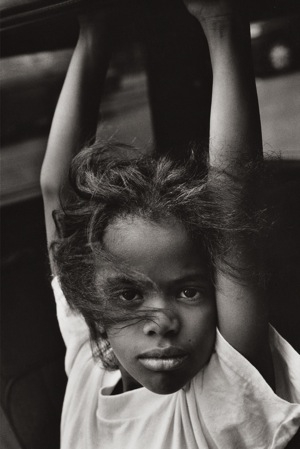

Photographer Profile - Eli Reed: "My work is about what it means to be human"

|

|

|

One of the films he saw was the 1962 classic Lawrence of Arabia, director David Lean’s exotic tale of adventure and war set against a vast desert backdrop. Reed was captivated by the movie—and by one scene in particular: “There was a reporter with a Speed Graphic camera at the top of a hill with Lawrence, surveying a battle, and I wanted to be on that hill with them,” Reed says. “It was a desire to be there, to see history.”

Cut to a real-life scene two decades later: In the mid-1980s, Reed, now a photojournalist with Magnum Photos, found himself covering the Lebanese Civil War, standing on a hill, looking at soldiers lined up for battle. “I thought, ‘Holy mackerel, this really is like a movie,'” he says.

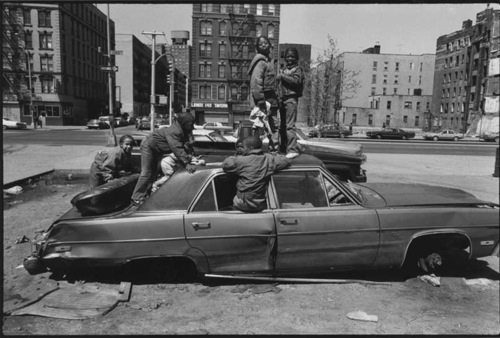

Photography has taken Reed farther than he ever imagined as a boy and allowed him to witness a wide scope of the world’s history over the past four decades. His path led from a small newspaper in Middletown, New York, to the San Francisco Examiner, and from there to conflicts in Central America, and then the war in Lebanon, which he documented from 1983 through 1987. That work led to his first book, Beirut: City of Regrets. He also covered the downfall of Baby Doc Duvalier in Haiti and the US military action in Panama. He covered the 1992 Rodney King riots in Los Angeles and the 1995 Million Man March in Washington, D.C., spent years examining poverty in America, and directed a documentary film about gang life in Detroit. He’s also managed to work as stills photographer on a number of Hollywood movies.

The thread that runs through all his work is his sense of empathy for his subjects, combined with a probing intellect that searches to explain why people do what they do.

“My work from the get-go was trying to discover what it means to be a human being—to ask ‘Why are we here? How long are we here? And what do we do while we’e here?’” he says.

Today, Reed works as Clinical Professor of Photojournalism at the University of Texas in Austin, while still pursuing his own stories between semesters. A couple of years ago, he began looking back at his life and thinking about doing a retrospective book. He eventually took a big box of his pictures to David Hamrick of the University of Texas Press.

“I wasn’t even sure what I had in there—I was just hoping it had stuff from my hometown,” Reed recalls. “But I plopped it down on his desk and he started looking through it, and after a while he looked up at me and he said, ‘You’ve got to do a retrospective.’”

A Long Journey

The book, out this month, is called Eli Reed: A Long Walk Home.

“I called it that because it’s about this long journey I’ve taken,” Reed says. “It’s a look back at my life, my entire career, from conflict to Hollywood to social issues.”

What the book is not is a collection of “best” images. Along with Reed’s photographs of historic events there are day-to-day scenes that hold an emotional meaning for him—for example, a shot of people in Central Park on a wintry day, with ice skaters in the background. It’s an honest appraisal of his life and his career as a photographer.

“This book is the essence of why I do stuff,” Reed says.

In the book’s preface, Reed traces his life’s journey, from a housing project to art school, from a job as a hospital orderly to a chance encounter with a photographer who gave him a new way of expressing himself. In a recent story about Reed at the New York Times’s Lens blog, David Gonzalez called Reed both “philosophical and impassioned” about the twists and turns of his career and highlighted a passage in the new book’s preface in which Reed talks about the influence of his mother, who died when he was 12:

What is it that we dream of in our brief illuminated time of consciousness? The realization and observation of possibility over a long period of time imply that the dead have beautiful dreams. I think of the death of my mother and what it meant to me. She was the subject of my very first photograph. I do not have the photograph. I have only the memory of her smile. That has been a good thing for me as I searched for the beauty inside the visual framework of life.

“If I were to kick off the planet [today], I’d feel that I had said

what I had to say,” Reed says. “And it can’t get any better than that.”

Spring Break

At the University of Texas, Reed teaches advanced photojournalism and multimedia journalism, with students reporting on Texas stories. “They do news, features and sports—it’s like working in a real news room,” he says. He’s also an unofficial advisor to the Daily Texan.

“A lot of famous photographers have come out of Texas,” Reed says, “and we want to carry on that tradition.”

In 2008, Reed took five of his UT grad students to Chicago to cover election night in Barack Obama’s hometown. Before they set out, he prepared them for what might be an emotional response to the election of the first black man as president.

Reed’s own view of race and racism has been formed from personal experience and from his work as a journalist.

“I remember one time a long time ago, I was working at this place with a coworker during a night shift. We were talking about something of interest, and all of a sudden he stopped and said, ‘You sound intelligent.’ What do you say when something like that happens?” he asks. “This wasn’t a bad person. And when you think of the kinds of things that have been said about the president, it’s just embarrassing, very embarrassing.”

The recent protests in Baltimore and the unrest in New York City and Ferguson, MO, following the deaths of black men at the hands of police have left him shaken. “It’s a very scary time,” he says. Having covered the riots in LA in the 1990s and other stories about racism in America throughout his career, he views the current events as nearly bewildering. “It seems that the powers that be never got the memo,” he says. Racial equality, he says, is a hard sell.

“And yet,” he adds, “we’ve elected a black man as president twice.”

Reed has seen a great deal of America and the world in the past decades. And he hasn’t given up looking.