The Portland Papers, Vol. 2

ILLUSTRATION AS AN ART FORM

I grew up in a working class family in rural upstate New York, surrounded by dairy farmers and deer hunters. But we had art, all done by members of our family filling every spare wall in our house. My Uncle Walt, a math teacher, painted the landscapes around Chautauqua Lake. My Aunt Ollie painted cats and ceramic ashtrays shaped like coiled rattlesnakes that she sold at the local flea markets. My Uncle Clarence, a World War II veteran, who was awarded a purple heart, drove a Wonder Bread truck by day, despite a gimpy leg. But, at night he drew comic characters for a correspondence course in How To Make Money Cartooning. In our fruit cellar stood a life-size Holstein cow made out of papier-mache sculpted by my mother. Art was always part of my life, but we never called it fine or commercial art. My family liked to work with their hands and the results were prized and admired.

In my senior year of high school (1956), I applied and was accepted to Pratt Institute, one of America’s prestigious art colleges. And during my freshman tour of the Pratt campus, I noticed a large totem pole made from compressed cardboard, near the Fine Arts building. The standing monument, done by a graduate fine arts student was titled, The Art Totem Pole. Under the title was scribbled “Freshman! You are about to choose your future!” Looking up I read the scrawled words in progression downward:

FINE ARTS IS PURE

ILLUSTRATION IS COMMERCIAL ART

GRAPHIC DESIGN IS NOT ART

ADVERTISING ART DIRECTORS ARE ART WHORES

Comic art and cartooning, no matter how original, did not appear on the totem pole or in the registration book. It was not art. No classes were offered in a discipline that most of us had grown up with and in fact had been our introduction to picture making and storytelling. Little did I know then that the content of that college graffiti would continue to define the categorization of artists in the art world.

Pratt, like the majority of art colleges, in America, requires that freshmen declare a major in their first year. Not uncomfortable with being an art whore I signed up for advertising art. My drawing skills were too weak for illustration and abstraction held almost total domination over the fine arts department. It would take a graduation and a job at General Motors to convince me that I had chosen the wrong major. My decision to quit advertising and graphic design had nothing to do with art. I learned that I hated working with people and collectively solving client problems. I went to Paris and a year later was drafted into the U.S. Army.

Once an artist has been typecast or categorized it is hard to break the mold. In the 60’s when art critics wanted to punish a painter they called his work illustrative. When an illustrator showed in a gallery the work was suspect. When a film director directed a television commercial they were placed on the Hollywood blacklist. To quote Thomas Hoving, (Introduction, Norman Rockwell: Pictures for the American People, published 1999, Abrams Books) former Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Of all the American artists of the twentieth century, few have been more miscast than Norman Rockwell. In most standard textbooks on American art, he’s not even included. He is characterized almost universally as an illustrator and as such is largely ignored or reviled or, worse, snickered at.”

Rockwell admitted (The American Magazine, May, 1936) there had been disadvantages to being an illustrator. “Many who consider themselves serious painters look down their noses at us. We paint for money, against deadlines, our subject matter often prescribed by an editor or an author.”

A brief glance backward may shed light on the

field of illustration and the question of content or subject matter. It is not my intent to delve deeply into American illustration history. That is another

book. There are, however, signposts and patterns in the history, relevant to our conversation.

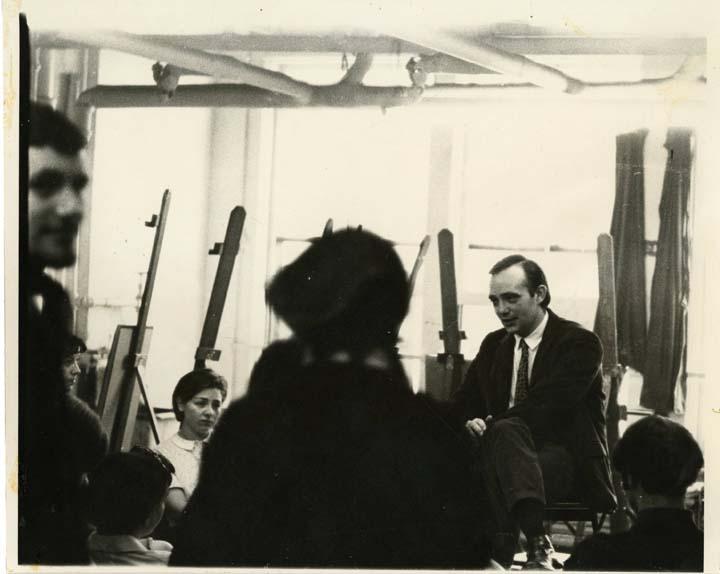

Marshall Arisman conducting his first illustration class at School of Visual Arts, in 1964.

By 1900 artists in Europe had taken over their own content, by-passing the traditional patron of church, state and the wealthy collectors. Cubism, Impressionism, Futurism, Surrealism and Dada followed. In America, Howard Pyle, the father of American Illustration, attempted to create a uniquely American painting movement by embracing the patron of illustration, the publishing industry. Webster’s Dictionary defines patron as a person or institution that gives practical (e.g. financial support) to a cause, individual or group regarded as deserving it.

For many American artists at the turn of the century the publishing industry as patron was very generous. By creating their own imagery—fine art, the illustrators were getting rich, along with the publishers. With the introduction, in the 1870’s, of the German process of chromolithography, full color paintings, could be reproduced in books and magazines. Business was booming.

In 1900 Pyle opened his own school, tuition free, in Wilmington, Delaware. He handpicked his students and determined how long they were to stay. In David Michaelisbiography of N.C. Wyeth (Harper Colllins Books, 1998), he said, “Pyle’s teaching was not the pure act of generosity that Wyeth and the rest of the Wilmington colony wanted to believe it to be. If magnanimity had been Pyle’s motivation for teaching, then it would not have mattered whether any of his students went on to make picture making their life’s work. But to Pyle it did matter. Students N.C. Wyeth were his lifeblood. He admitted and graduated students only if their future, like Wyeth’s could be certified “a future of positive success.”

Pyle tolerated nothing less than absolute dedication to his crusade. “Illustrate the words of the Great American authors, read and re-read them until they become your own”, he said. “That, is the future of American art making.” (N.C. Wyeth Harper Collins Books, 1998)

As publishing expanded from books to magazines it became clear that the real money was not in selling beautiful illustrations on the printed page but in selling the page to advertisers. The patron of illustration had become an employer. With no union to arbitrate for them, the freelance illustrators had no choice but to follow the marketing trends and paint images to sell products or leave the field.

In the 1920’s, Fine Artists turned to illustration as a second job to support their personal art. To quote Lewis Hyde in The Gift (First Vintage Book’s Edition c 1929,1980,1983 by W. Lewis Hyde)

“For years before he established himself as a painter, Edward Hopper used to hire himself out as a commercial artist to magazines with names like Hotel Management. Hopper was an expert draftsman, and the illustrations and covers he drew during those years are skillfully rendered. But they are not art. They certainly have none of Hopper’s particular gift, none of his insight, for example, into the way that incandescent light shapes an American city at night. Or perhaps, I should put it this way: any number of out-of-work art students could have drawn essentially the same drawings. Hopper’s magazines covers—happy couples in yellow sailboats and business men strolling the golf links—all have the air of assignments of work for hire. Like the novelist who writes genre fiction according to a proven formula or the composer who scores the tunes for television commercials, or the playwrights flown in to polish up a Hollywood script, Hopper’s work for the magazines was a response to a market demand and the results are commercial art.

During his years as a commercial artist, Hopper spent only three or four days a week at the magazines and he painted at home the rest of the tie. He would, of course, have been happy to sell his paintings on the market but there were no buyers. In 1913, when he was thirty one years old, he sold a painting for $250; he sold none for the next ten years. Then, between 1925 and 1930, he began to earn a living by his art alone.”

The content for an illustration is supplied by the writer of the story; article etc., not the illustrator. The Art Director of the Agency or company is given the content by the editor, and the A.D.’s job is to find an illustrator whose style he/she believes can reflect the written content. Of course, if the chosen artist can add a visual twist while reflecting the content, so much the better. Illustrators are proud to say that Michelangelo was an illustrator. The content of his paintings in the Sistine Chapel was assigned by the Pope, as Art Director. It is a weak argument, as is the notion that Edward Hopper was an illustrator.

In 1979, Robert Weaver, the undisputed pioneer of contemporary American illustration, was asked if illustration was Art. (Print Magazine, Robert Weaver’s Illustration issue, November/December 1979)

He replied, “No. It is only a profession whose best practitioners may one day be remembered as artists. The state of the art of illustration might be compared to a third world country: it has not yet gained control of its technology. Editors and design consultants, not artists, shape the magazine. For a work to be judged as art there must be an artist in full command of his medium. Only when he has pushed it as far as it can go can he be tested fairly by the same critical standards applied to other artists.”

Taken from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia is the following assessment of Robert Weaver whose ideas, in great measure, re-defined the illustration/fine art controversy and is partly responsible for the variety of artwork seen in galleries and publications today. Personal work that in earlier times would be dismissed as “illustration” is now accepted as “figuration,” and meets the criteria for fine art.

Robert Weaver (July 5, 1924 – September 4, 1994) was an American illustrator who was considered a pioneer of a contemporary approach to the field that began in the 1950’s. Beginning in 1952, he embarked on a mission to combine the visual ideas found in fine art with the responsibility of the journalist. At the time, many practitioners of illustration were expected to paint and draw for advertising and magazine assignments with artwork that was conservative, idealized and saccharine, while other illustrators such as Ronald Searle, Arthur Szyk, George Grosz, Kathe Kollwitz and later Ralph Steadman and Toni Ungerer injected their own opinion into the assigned material. Weaver joined this latter tradition by moving his role of an illustrator from a page decorator to a journalist. He ventured from the typical haven of an illustrator’s studio into the world and used a pencil to observe, record facts and draw real life based visual essays, the way that illustrators, Burt Silverman and Franklin McMahon did. This approach would later be termed “visual journalism” and in 1983, Robert Weaver would join a special Masters Degree Program, Illustration as Visual Essay at The School of Visual Arts in New York City, chaired by Marshall Arisman.

After a successful career as an illustrator, Weaver withdrew from the illustration business in the late 1970’s. Parallel to teaching he now created experimental visual essays. Free from the illustration art market he explored his personal vision, defined as fine art although not by him by investigating sequentiality with multi-perspective narrative. In spite of a serious eye affliction, he continued to draw. At the time of his death he had completed over one hundred visual essays in book form—each unique and original.

It was my feeling that personal storytelling in the newly formed MFA Illustration program at Visual Arts, should be preceded by the student interacting, both visually and in written form, to the world around them. It was clear to me that expressing a personal vision would follow.

In the 1986 PRINT Magazine (January/February issue) ran a cover story about the program, introduction by Steven Heller.

“In 1984, the School of Visual Arts in New York began its first MFA Illustration program, “The Illustrator as Visual Journalist.” Under the chairmanship of Marshall Arisman, this course of study is a radical departure from the accepted method of teaching illustration as an adjunct to someone’s text. The two-year program is designed to encourage artists, be they painters, cartoonists or illustrators, to expand the boundaries of illustration into the realm of journalism. By reporting on the current scene and commenting upon events and issues through text and image, the students learn to develop a less decorative, less symbolic and ultimately a more communicative form of illustration.

This is not really a new idea. It builds upon a two hundred year old tradition, and furthermore, borrows from the teachings of some contemporary illustrators. It is, however, the first intensive program to encourage the reapplication of an all-but-extinct practice.

From the historical standpoint, virtually since the beginning of newspapers there has been visual journalism. Before the camera and long before the photograph could successfully be reproduced in print, the reporter’s drawing of an event or celebrity (reproduced by lithography, etching or woodcut) was the way to record and transmit information. Graphic commentary--a more critical form of journalism--was decidedly more powerful in the 19th century than any printed word could be. And, for decades after the photograph became the major media, “specials”, as illustrator/journalists were sometimes called, covered the stories that no one else could—or would.

Ultimately, though, the quick and economical accessibility of modern media, including the photograph, film and television made the objective illustrator obsolete. Some magazines, such as Fortune, Holiday, Sports Illustrated and more recently, Rolling Stone, have continued the practice as a counterpoint to photography. But this coverage is primarily used for features rather than hard news stories. And, since photographers have limited access to courtrooms or hearing rooms, the court artist is virtually all that remains today of the illustrator-reporter.

Illustration reportage cannot compete with the electronic media. The illustrator cannot be truly objective; moreover, the hand is unable to freeze reality as the camera does. But illustration is a viable alternative to conveying certain stories from an objective photographic perspective.

The stories on the following pages illustrated the varied levels on which the illustrator as journalist successfully functions. These graphic essays are based on an assignment called “Isolated Positions,” which required that the student report on someone whose life is lived in some degree of isolation. The students were encouraged to interpret the problem in any logical manner, to expand upon the premise, and to deal ultimately with a world that is larger than their usual surroundings. Their reports are about groups and individuals whose stories are rarely, if ever, told. The dynamic manner in which they are covered signals a substantive new approach to teaching illustration.

We made arrangements with nursing homes, The Fortune Society, women’s shelters, halfway houses and hospitals where students could go, interview and create visual essays—all with the help of the core faculty, Arthur Pincus, Steven Heller, Jim McMullen, Robert Weaver and myself.

Visual Journalism is, unfortunately, a very thin slice of the illustration market. Editors are wary of assigning multiple pages to human-interest stories to illustrators believing that the subjects might be better served by photography.

The word journalism continued to attract applicants who drew political cartoons that were overstated and crudely drawn for their college newspapers. A second group of applicants wanted to become courtroom artists with a salaried position at a major network. The title, The Illustrator as Visual Journalist, was no longer broad enough.

In

1990 I changed the name of the program to Illustration as Visual Essay. Visual Journalism became part of the required curriculum that continues today. The focus of

the program, my original intent, shifted to storytelling in all forms—visual journalism, children’s books, graphic novels, illustrated novels, comic books and visual essays for gallery

walls.

Faculty member David Sandlin critiquing a mural done for the MFA

Illustration as Visual Essay program, date tktktkt.

2014 is the 30th Anniversary of the program. Looking back on this thirty-year quest to reinvent the way illustration is taught at the graduate level at the most evolved art school in the country, it now seems as if it has been a logical progression. It began with a personal discontent, not only with the existing field of illustration in the late 1960’s but, also with my personal experience in it as a free-lance illustrator. Visualizing content, not my own, was unsatisfying. And certainly did not begin to use my mind nor encourage my desire to explore new ways to approach the page technically to make an idea come to life. At that time and to some degree still today, illustration portfolios feature editorial or advertising samples that proved an artist was professional and therefore capable of executing an editor or art director’s idea.

The illustrator is now stepping outside the market dominated by those editors and art directors and becoming his/her own patron. The opportunity to illustrate someone else’s story still exists to provide extra income but it is the creative personal work that exacts the enthusiasm and interest of the marketplace. By the time they graduate our students know and have experienced using that work as the primary way to replenish the vital energy needed to live a successful life as an artist. It is also the energy that invigorates their roles as teachers for those who choose to teach.

Thirty-five years later, illustrators have gained more control over their medium, the result of technology. Editors and design consultants continue to dominate the magazines, but with the advent of self-publishing and the Internet, illustrators now have the opportunity to take “full command of the medium,” and visually express a personal vision. Artists are now expected to be fresh and unique and to initiate pictures and ideas for all media—not only for publishing but, for film, the internet and for gallery walls, once reserved for “fine art.”

Storytelling in the hands of the contemporary illustrator can now be judged as an art form. And under the age-old definition of fine art, the personal vision expressed in the work created by the artists we graduate qualifies them to be regarded as true artists—fine artists, if you will.

Editor’s Note: This article is first in a series of presentations made at ICON8 in Portland. The ICON8 Educator's Symposium celebrates new and innovative methodologies for teaching illustration in the 21st Century. This two-part event at the Pacific Northwest College of Art as part of the ICON8 pre-confernece workshops, July 9-10, features a presentation of papers by a global selection of noted educators, and a round-table discussion on traditional and online learning. Produced by ICON8 education board chair Rick Lovell, Illustration Program Coordinator, Savannah College of Art and Design with ICON8 vice president Robert Brinkerhoff, Department Head, Illustration, Rhode Island School of Design.

The paintings and drawings of Marshall Arisman have been widely exhibited, both internationally and nationally. His work may be seen in the permanent collections of the Brooklyn Museum, at the National Museum of American Art and the Smithsonian Institution, as well as in many private and corporate collections.

Mr. Arisman's original graphic essay, "Heaven Departed," in which paintings and drawings describe the emotional and spiritual impact of nuclear war on society, was published in book form by Vision Publishers (Tokyo, 1988).

Chairman of the M.F.A. degree program at the School of Visual Arts in New York City, Marshall Arisman was the first American invited to exhibit his artwork in mainlandChina. His series, "Sacred Monkeys," appeared at the Guang Dong Museum of Art in April 1999.

Mr. Arisman is the subject of a full-length documentary film directed by Tony Silver titled "Facing the Audience: The Arts of Marshall Arisman." The film will have its premier showing at the 2002 Santa Barbara Film Festival. Angels/Demons. The Third I.

ICON: The Illustration Conference is committed to providing a forum for an ongoing dialogue that serves the illustration, design, publishing, advertising, and academic communities. Its purpose is to provide a platform for the most influential illustrators and industry leaders to address, in a timely manner, the most pervasive issues facing the profession. Illustration Conference (ICON) is a 501 C-6 nonprofit organization of illustrators and is an entity in itself. ICON remains the only national conference specifically for illustrators and the graphic arts community providing an unprecedented forum for the creativity, inspiration and drive that captivates the profession. ICON8 Education Program is chaired by Rick Lovell, Illustration Program Coordinator, Savannah College of Art and Design.